Mobile families oppose Alabama Power’s coal ash pond being capped in place on the Mobile River: Walter Simon

By Walter Simon and Glynn Wilson –

MOBILE, Ala. — It was supposed to be an open public hearing for public engagement about a plan by Alabama Power to cap and close a giant coal ash storage pond by the Mobile River. But when people showed up at the Hampton Inn in Saraland on Tuesday, they were informed that the motel management would not allow members of the public, the press or media or activists to congregate inside the motel or in two hearing rooms rented by the Alabama Department of Environmental Management to take public comments, a requirement of the law.

About 80 people signed up to speak in advance, but they were told they would have to sit in their cars in the parking lot and be called in one at a time to make comments lasting no more than seven minutes.

The state agency charged with protecting the environment through regulations, set up back in the 1980s as a one-stop permitting agency for industrial pollution permits, said a video of the comments would be posted on its YouTube Channel.

Outside in the parking lot, Richard Moore, a former U.S. Attorney and inspector general for TVA back during the Kingston, Tennessee coal ash spill in 2008, made comments to the media opposing the permit and calling on Alabama Power to be a good corporate citizen.

Watch Video: Coal Ash 1A – SD 480p

While coal ash controversies rage across the country as other power companies deal with disposing of the toxic byproduct of burning the fossil fuel coal for energy, Alabama Power, a division of Southern Company, is choosing what’s called a cover-in-place method for the 600-acre pond at Plant Barry in Mobile. The coal would be compacted by sucking the water out of it and covering it with a synthetic liner, topsoil and vegetation.

The problem is that would leave the coal ash full of toxic substances harmful to human health to leach into the surface water, ground water, drinking water and the Gulf of Mexico forever. Coal ash is not only radioactive, it contains many of the chemicals and heavy metals regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency in other industrial uses, including arsenic, chromium, lead and mercury.

Because of power industry lobbying back in the Bush-Cheney years, it was granted an exemption from the law under the Resources Conservation and Recovery Act and is treated as “solid waste” — the same designation as household garbage — not “hazardoes waste,” which would require it to be dug up and disposed of in a properly lined hazardous waste landfill.

The power company claims in its heavy-handed public relations campaigns, paid for with millions of dollars in ad buys in newspapers, on television and the web, that it is spending $3.3 billion over the next several years to close its six coal ash ponds around the state. The company, which was set up as a quasi-public-private utility but for years has been run as a corporation with a guaranteed profit margin by the Alabama Public Service Commission, announced it would be passing that cost on to consumers, raising electricity bills by 3 percent in 2020 alone.

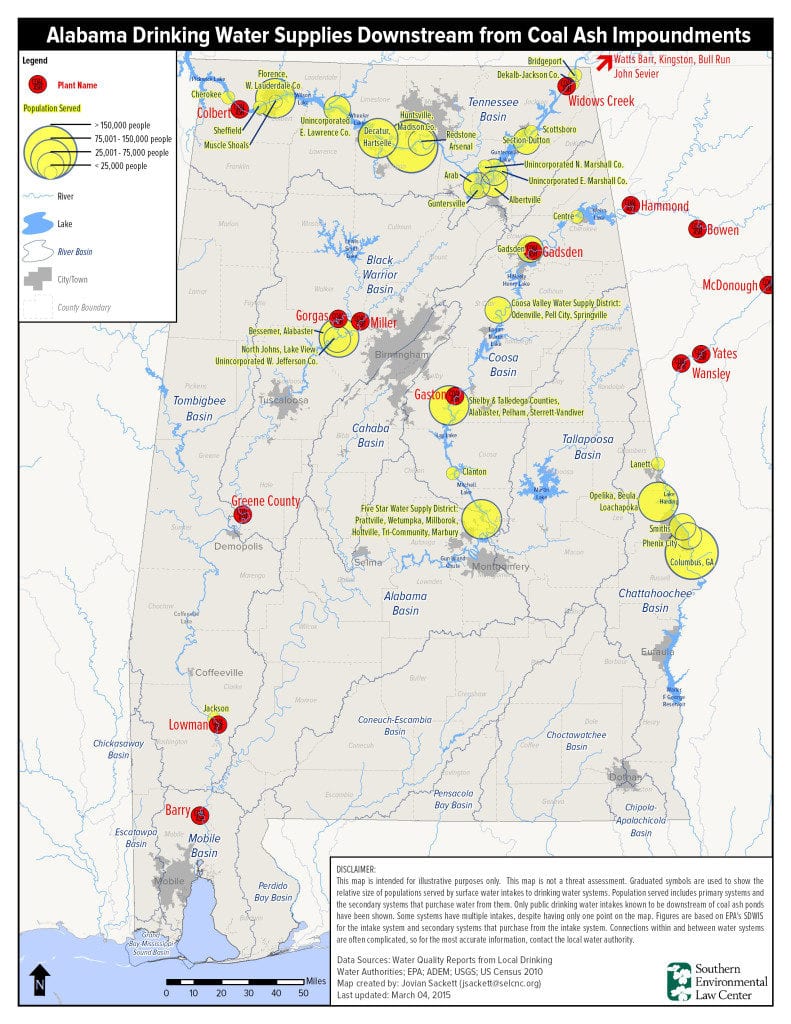

This map shows Alabama drinking water sources downstream from coal-fired power plants’ coal ash waste impoundments, which discharge tens of millions of gallons of polluted wastewater into Alabama’s water resources every day: SELC

In a statement issued about the Plant Barry meeting, Alabama Power called the public hearing a “routine part of the permitting process” and said the company supports it because it “provides the public an opportunity for continued engagement.” The public may submit written comments through April 6.

In other states, about 250 million tons of coal ash is being removed from holding ponds in Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee and Georgia, and in some places, the ash is being recycled into other useful products such as concrete.

Critics of Alabama Power’s approach say the location of coal-ash ponds near sensitive waterways and the Mobile-Tensaw Delta will always be a concern for the potential of a catastrophic spill or dam collapse, like the one that happened at a Tennessee Valley Authority plant in Kingston, Tenn., in 2008, or in the likelihood of a major hurricane hitting the Gulf Coast.

Related: Toxic Coal Ash is Back on the Agenda as an Environmental Issue of Our Time

Coal ash is the dirtiest fossil fuel of them all, along with oil and gas, and it is a major contributor to climate change from global warming, which is projected to lead to even more large storms in the future with more devastating impacts in coastal areas. Experts say the best way to deal with it would be for the Biden EPA to regulate is as a hazardous waste, forcing power companies to dispose of it properly.

Related: Reversing Trump Policy, Biden EPA Brings Back Climate Change Science Online

More Photos