He Shot Rock ‘n’ Roll Too

EDITOR’S NOTE: We caught up with Scherman and got this story we ran on August 6, 2011 in The Locust Fork News-Journal. We re-run it here today because we are about to hook with Rowland again in New York on a trip to meet up with author and new journalist Gay Talese.

How many roads must a man walk down

Before they call him a man?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the wind.

— Bob Dylan

Rowland Scherman at Art Folk, Inc., “We Shot Rock ‘n’ Roll”: Glynn Wilson (See video, links and purchasing information below)

by Glynn Wilson

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — Running into Rowland Scherman at the “We Shot Rock ‘n’ Roll” show the other day made me think of a story I picked up from a professor who taught a class at the University of Alabama on the history of “Rock ‘n’ Roll,” a story packed with advice about how to live life and succeed.

Scherman was in town for a special show at a downtown gallery since none of his works were included in the Birmingham Museum of Art show going by a similar name out of Brooklyn, New York. When I saw the announcement about the Museum of Art show, I planted the idea on Facebook to get Rowland back down here, since his name was not on the list of photographers and I knew he had some of the most iconic pictures from the beginnings of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

At the time Rowland was running Joe bar on Birmingham’s Southside in the early 1980s, I was a student of journalism and photography at the University of Alabama, fully engrossed in reading authors like Hunter S. Thompson, and ordering Bass Ale, because that’s what Thompson drank at the Watergate Hotel. Joe was about the only place in Birmingham you could get it then.

The professor in question, Jim Salem in Tuscaloosa, liked to say when the bus pulls up to the station, no matter what your dream, you better have your bags packed and be ready and willing to get on that bus and go. When opportunity knocks, that is, you get on the bus.

Photographer Rowland Scherman got on that bus, in 1957, and he’s still on it, although sometimes these days, it’s a train or a plane taking him to the big picture.

Let’s just say Rowland Scherman was there, for some of the most important cultural moments of the 1960s and beyond.

He was there at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963, when Bob Dylan showed up as a guest of Joan Baez and went from “zero to hero” in one weekend.

The next year, he was there when the “British Invasion” began, when The Beatles played their first concert in the United States, at Washington Coliseum in D.C. on Nov. 2, 1964.

He was there in D.C. when Bob Dylan went electric and he caught that iconic early image of Dylan that quickly became the cover of Life magazine, and later the album cover that won the grammy for Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits.

And yes, Virginia, near the end of the “Decade of Peace and Love,” he was there in the summer of ’69 at Woodstock, thanks to his friendship with Judy Collins, who was crazy in love with Stephen Stills of Crosby, Stills and Nash.

An Artistic Eye

It is not enough to just say he was there, however, and many other interesting and important historical places and moments over the course of a life. He possessed a camera, and an artistic eye. Not just the eye of a photojournalist. At heart he’s always been a portrait artist, “not a hard news guy,” he says.

Rowland possessed a few cameras over the years in fact, and sort of knew how to use them, as he tells the story in his humble way these days. They say the ego mellows with age.

Scherman turned 74 in April. But he does not look 74, or act it.

Joe Bar

He is as cool today, maybe cooler, than that day in 1980 when I met him at Joe Bar on Birmingham’s Five Points South. He was in the full throws of his curmudgeonly 40s then, running the coolest bar in the history of Birmingham.

Scratch that. The coolest bar ever, in any town this side of Scotland.

That’s not a bad thing to have on your curriculum vitae. “I once owned the coolest bar in the world.”

That’s how a lot of people in Birmingham came to know and love Rowland. It was almost like the 1960s didn’t make it to Alabama until Rowland did.

But that’s not what he came back this year to talk about.

It’s the images he captured over the years that are now under scrutiny, as he and a team in Massachusetts go through the archives and take a fresh look at what’s there.

The Story of Success

The story of how he got all those iconic images — and his life story — is a similar story to other successful artists. The timeline of his life in fact parallels other major successes of the 20th century, stories told in the groundbreaking Malcolm Gladwell book Outliers: The Story of Success. You’ve heard the story before.

A lot of Scherman’s success can be attributable to luck, just being in the right place at the right time. The same could be said for another semi-famous Birmingham photographer of the same era, Spider Martin, as well another great friend of mine, writer Rick Bragg.

Rowland got his start in 1957, the year I was born, the year of Sputnik. Rowland was 20. He was born in April, fairly early in the year, and by the time he worked for Life in New York City, the Baby Boom was underway across the land. That would soon be followed by the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s.

But no success can solely be attributed just to luck. There is also preparation, determination, an eye for the craft — and a zest for life.

What’s the famous formulae for success? Where Desire, Preparation and Opportunity meet?

That was Rowland.

“It was serendipity,” Scherman will tell you, if you ask about how he ended up in those places — and came away with THE shot.

As he told the story in a talk last Sunday at Art Folk, Inc. on First Avenue North in downtown Birmingham, he got his hands on a camera early on in the 1950s. Like many photographers, he started taking pictures of his family, the dog, and especially his brother, who went on to build the life-sized Nautalus from the film Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea for Euro-Disney.

The intro photo in the slide show for Rowland’s talk is a picture from the first roll of film he ever shot. It’s of his brother with the Nautalus model he built after seeing the movie when it came out in 1954. Rowland says his brother was his favorite person to photograph, and he dedicates the show to Tom Scherman. The final photograph in the slide show is one of his brother aboard “the real Nautalus” in the year of his death.

“I loved him and miss him every day,” Rowland says.

Rowland Scherman giving a talk with a slide show at Art Folk, Inc. That’s the picture of his brother with the Nautalus on the screeen: Glynn Wilson

As the movie was an epiphany for Tom that led to his life’s work, the photograph was an epiphany for Rowland.

“This is what I want to do, continue to take portraits,” he said to himself. He went back to Oberlin College and changed his major to art.

“I started shooting everything, although I really didn’t know what I was doin’,” he says. But looking back at some of the photos now, like an out of focus picture of a drummer with sticks moving in the air, Scherman says, “I didn’t know what I couldn’t do.”

Life Magazine

Scherman got his start in photography at Life magazine in New York City, at first as a young “hypo-bender,” mixing the chemicals. He mixed developer and fixer in giant vats on the 40th floor of the Time-Life Building in New York, one floor up from the famous 39th floor, home to the massive Time-Life dark rooms. He also made contact prints from the work of other photographers. He was born and raised in Pelham Manor, New York, an old town with American Revolutionary history a little north of Manhattan.

At Life, Scherman got to work with the best before television began to eat into the market for magazines and print newspapers, and he became one of the best while shooting for Life himself, capturing The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and the likes of I.F. Stone, one of Scherman’s personal heroes — along with “Mickey Mantle and John Lennon.”

“I got my feet wet in photography at the ground level,” he said. “But I also associated with the big stars of photography, so I was really quite lucky.”

The first “real camera” he bought was a Nikon S2 Rangefinder.

The Peace Corps

He was also a fan of John F. Kennedy in the early 1960s. Scherman was taken in by the Kennedy speech announcing the creation of the Peace Corps during the 1960 presidential campaign at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor on October 14, 1960, so he showed up at the new office in D.C. “to do something for my country,” he says. He wanted to be the first Peace Corp photographer.

Since the Peace Corps was just an idea when he first showed up in D.C., there was no place for a photographer, he was told.

“We don’t need photographers, kid,” they said, since the place was “crawling with photographers,” in his words. They followed Kennedy wherever he went.

Rowland said, “Let me stick around anyway.”

“They said OK,” Scherman says, although Sgt. Shriver’s people, including his assistant, the young Bill Moyers, were looking for doctors, farmers, teachers and technicians.

When Kennedy left, however, and the photographers left with him, the next day Princess Beatrix of the Netherlands showed up to help the new agency, and somebody came running, saying, “Hey, where’s that kid with the camera?”

Right place. Right time.

The Kennedys

Rowland later photographed both John and Bobby Kennedy before they were killed so tragically. Unfortunately, the best photographs from Bobby’s 1968 campaign were shelved, for 40 years, until recently. Scherman showed some of them during the talk, becoming especially emotional talking about the death of JFK and Bobby. He had taken a few days off and wasn’t there to cover Bobby’s shooting.

“When JFK was shot I didn’t carry a camera for days,” Rowland told me in an e-mail interview in the days after the show. “I was devastated.”

Bob Dylan

How did Scherman end up at Newport that weekend with Bob Dylan?

He found out Peter, Paul and Mary were going to be there for the folk music event.

“I was crazy about Mary,” he says, “so I had to go see her.”

That first day, he ran into a skinny guy with fuzzy hair with a bullwhip on one shoulder and a guitar, smoking a cigarette.

“I only shot this one picture,” Rowland said of Dylan that first day.

“I said your cool,” he recalls telling the future legend. “I want to do a story about you.”

Eventually he did the photos, for Life.

But he kept shooting through the weekend, and by the end, Peter, Paul and Mary were singing backup to Bob Dylan.

“He went from nothing to the biggest act in folk music that weekend,” Scherman said. “It was just blind serendipity, blind luck that got me there that weekend next to Dylan.”

The Beatles

How did Rowland end up at The Beatles first American show?

Scherman’s sister, who was working with photographer Robert Freeman, called and said, “You better come see these guys.”

“I didn’t have a press pass. I didn’t have a ticket,” he said, laughing. “But I got closer and closer and nobody saw me. Pretty soon I ended up with my elbows on the stage. You couldn’t miss.”

He went to the cast party after the concert at the British Embassy, and you could tell, he said, that The Beatles were “just amazing. Ringo was the sweetest.”

“Incidentally,” he said, “the Beatles were the act that took the gloomy headlines of JFK’s assassination off the front pages for the first time since the previous November. I guess people realized that music is going on, life is going on, and The Beatles helped that.”

The Grammy

The Dylan grammy shot came at another concert in D.C., two years after Newport when Dylan went electric.

Rowland was there, camera ready.

This time, however, they tried to stop him from going back stage.

“I said screw you, Life magazine, get out of the way,” Rowland says with that New York smirk that makes him endearing to those who can appreciate it. “It was baloney, but I was shooting for Life. I didn’t have an assignment, but I just wanted to do it. I couldn’t be stopped. Bullshit works sometimes when you are sure of yourself.”

A sentiment shared by many a journalist, including myself, who have employed the tactic ourselves from time to time.

When he got the invite to go to New York for the Grammy Awards, there was a snow storm, he recalls. He didn’t think much of his chances, so he passed. When the award came, it was broken, and his name was misspelled.

“But then, my mother couldn’t spell my name,” Rowland said, joking around.

He went on to photograph bluesman Mississippi John, Woody Allen, President Lyndon Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., Louis Farrakhan, Arthur Ashe, and even Jimmy Hoffa. While the rest of the press was looking for Hoffa coming out of the jail, Scherman looked the other way — and caught him riding by in a car, still in handcuffs, shooting a peace sign.

Another nailed opportunity.

Woodstock

Scherman got the assignment to photograph Judy Collins, who was in love with Stephen Stills. He did a double shoot with Joni Mitchell and Collins, and he found out that Crosby, Stills and Nash were playing in upstate New York at a place called Woodstock. They called the event, “An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music.”

“I went along,” Rowland said. “With 350,000 of our close friends.”

He was on stage to photograph Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, Crosby, Still and Nash, and others, and still has some of the most iconic shots from the festival.

Back to New York

After that, he moved back to New York City, and did some movie work, capturing Sammy Davis Jr. and others, and shot the cover photo for Playboy, perhaps the best selling issue of all time, although I believe it was outpaced by the Jessica Hahn issue in the late 1980s, at least according to my sources in the NewsBreak business.

London

In 1970, he said to himself, “Screw New York,” and went to Europe. He wanted to follow The Beatles and others on that meditation quest to the Far East. To hook up with “the Maharishi guy in India.”

“But I was having so much fun in London that’s as far east as I got,” he says, laughing again.

While in London, he saw a protest march going by Hyde Park one day and ran to the front to see what it was about, who was leading it. There were John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

He moved to Wales for awhile, then came back to New York in 1979 but, he said, “It was getting cold. There was garbage piling up in the street. It was Calcutta by the Hudson. I was stepping over bodies in the subway.”

Moving South: Birmingham

Wanting to “go someplace else,” he said, he called up the late Bill Bagwell, who had an advertising agency in Birmingham.

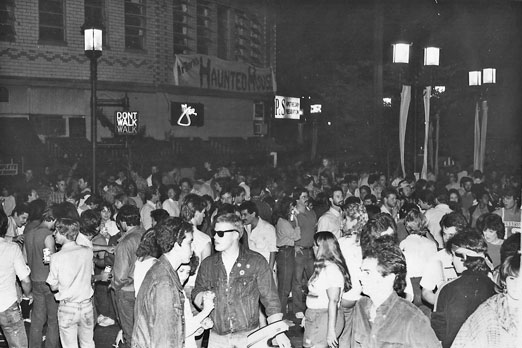

“He said come on down. I came for two weeks … and stayed 20 years,” Rowland says with a bit of a New York growl, funny and familiar to his friends from the Joe bar days, the 1980s. It was the Heyday of Birmingham’s Southside.

I was there, first hanging out at Joe in the early 1980s with the likes of author Dennis Covington, who taught creative writing at UAB. In 1986, I opened the first newsstand-coffee bar on Southside myself, a store called NewsBreak.

When Rowland came to Birmingham right after London, he thought Southside needed a pub with a selection of imported beer. Joe also got in on one of the martini crazes, making one of the best anywhere, according to Brooks Boliek, the editor of the Kaladoscope in 1982-83, now with Politico in Washington.

I came back after a few years in the newspaper business in 1986 and thought Southside needed a newsstand-coffee bar. I almost ended up leasing the space two doors down from Joe for my shop, but the old Studio Arts Building burned down and Newsbreak ended up at Highland Avenue and 30th Street. Two years later, in 1988, I opened a second store in Five Points, but Joe had moved to Seventh Avenue in the Lakeview area.

Scherman sold the bar in 1984 and shot fashion models for Pizitz and Parisian, among other things, then embarked on an art project to document U.S. Highway 11. He later did a book of photographs of Elvis iconography. The book didn’t become a big hit, in part because it was released the same day President George Hurbert Walker Bush threw up on the prime minister of Japan, Rowland says. A couple of weeks later in 1992, the war called Desert Storm took over the headlines.

“Every failed author has an excuse,” Rowland says. “That’s a pretty good excuse.”

So he went to Mexico, and photographed the Mayan pyramids, and the walls of Mexico.

Cape Cod

He came back to Birmingham, and scratched a living for the next few years, until the year 2000, that fateful year when George W. Bush was elevated to the presidency by the U.S. Supreme Court after the hanging chad fiasco in Florida. Scherman pulled out of the conservative Bible Belt and moved to Orleans, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod. He has ongoing projects on Automobile iconography, and “neon women.”

China

Due to his connection to the public relations staff for Mercedes, however, who he met when the German automaker opened its plant in Vance, Alabama, Scherman finally got his chance to travel to the Far East. He took several trips to China. There he saw “a picture of the future,” he says.

In a hint to the younger generation in the U.S., watching the decline of the American empire and the rise of China now, their “thriving middle class,” he suggests taking a close look at visiting or even moving to China. Perhaps if he were young again, that might be the place to be.

“But learning Chinese is problematical,” he says.

The right place? The right time?

With a little luck, who knows?

Missed Opportunities?

Rowland is reluctant to talk about any missed opportunities over the years, but let’s face it. Nobody is always “there.”

But Newport was “one of those great times,” Rowland says, talking about that weekend while looking at one of his photos of Dylan and Joan Baez together in the gallery show (see video below).

“We were young. There was no end to it,” he said. “I don’t think we slept.”

But you can’t be everywhere, all the time.

“There were many times when my bag wasn’t packed, and I flubbed the dub,” Scherman admits. “Sometimes you eat the bear. Sometimes the bear eats you.”

Watch A Video of Rowland’s Show Party at Art Folk, Inc.

He was the subject of a documentary than ran on public television in 2013.

Turning The Lens On Renowned 60s Photographer Rowland Scherman

Where to See and Purchase Rowland Scherman Photographs

You can see some of Rowland Scherman’s photographs on a new Website at SnapsTour.Com, and purchase prints here.