The Big Picture –

By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. – You know it’s the end of an era when a giant passes from the Earth.

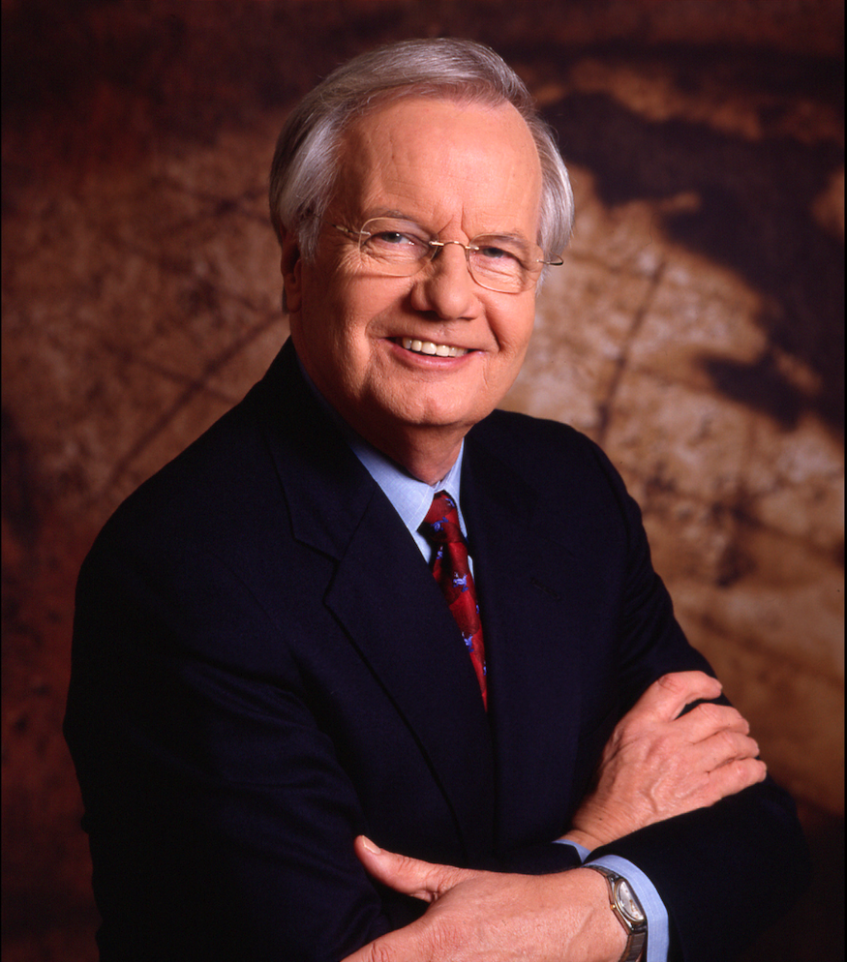

Bill Moyers, who made it to the Big Time from small town Baptist roots in Texas in the 1950s to the White House in the time of President John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson in the 1960s and became the conscience of a great nation in the early days of television news at PBS and CBS, died on Thursday in New York. He was 91.

His son William Cope Moyers confirmed the death at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan., according his feature obituary in The New York Times. No cause was given. We hope he died peacefully in his sleep of natural causes.

His timing in life could not have been better. He got his start in journalism at The Marshall News Messenger in high school in the 1950s, later crediting publisher Millard Cope with encouraging his interest in public affairs. He went on to study journalism, government, history, theology and ethics, he said, in “deliberate preparation for a career in public service.”

“He served as chief spokesman for President Lyndon B. Johnson during the American military buildup in Vietnam and then went on to a long and celebrated career as a broadcast journalist, returning repeatedly to the subject of the corruption of American democracy by money and power,” as the Times writes.

To those of us Americans who grew up in the era of television in the 1960s and ’70s, the Baby Boomer generation, Moyers became an authoritative voice you could trust in times of crisis up there with Water Cronkite. Journalist and author Peter J. Boyer once described him as “a rare and powerful voice, a kind of secular evangelist.”

But he had set out for Washington in the early 1960s to be involved directly in politics and government. As President Johnson’s closest aide, he ended up on Air Force One in Dallas when Johnson took the oath of office after Kennedy’s assassination. Working with President Johnson, he played a pivotal role in developing and promoting Johnson’s Great Society programs, and was the president’s top administrative assistant and press secretary when Johnson sent hundreds of thousands of troops to fight in the war in Vietnam.

Moyers resigned from the administration in December 1966 at the age 32 after an irreparable falling out between the “hot-tempered, flamboyant Johnson,” as the Times described him, “who demanded unwavering loyalty.” Johnson had denied Moyers’ requests to join the Foreign Service overseas, the Times reports. The two men never reconciled, and in his 1971 memoir, The Vantage Point: Perspectives of the Presidency, 1963-1969, Johnson barely mentions Moyers, trying to reduce him to a footnote.

It is highly likely that Moyers joined Jack Valenti in the administration urging Johnson to reconsider escalating the war in Vietnam, first started by Kennedy with a few thousand “advisers” to the South Vietnamese Army, although he never spoke directly about that publicly. The escalation became Johnson’s undoing, forcing him to step away from running for reelection in 1968. It would not have been Moyers’ style to say “I told you so.”

But Johnson’s snub did not break Moyers or stop his advance in the public eye.

In his four decades as a television correspondent and commentator, Moyers explored issues ranging from poverty, violence, income inequality and racial bigotry to the role of money in politics, threats to the Constitution and climate change. His documentaries and reports won him the top prizes in television journalism, more than 30 Emmy Awards and comparisons to Edward R. Murrow, his revered predecessor at CBS.

“In an age of broadcast blowhards, the soft-spoken Mr. Moyers applied his earnest, deferential style to interviews with poets, philosophers and educators, often on the subject of values and ideas,” the Times writes.

His PBS series, “Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth,” in 1988 drew 30 million viewers, posthumously turning Campbell into a public broadcasting star. Campbell died before the series aired, but became famous for his saying, “Follow your bliss.”

Many in my generation followed that advice, including me, with varying degrees of success.

Conscience of a Nation

Moyers became the conscience of a nation in a way, bringing to his work what one television critic called “a sense of moral urgency and decency.” Putting himself in the story in his way, it was a form of new journalism pioneered in print by Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Jimmy Breslin, Norman Mailer and Hunter S. Thompson, the doctor of Gonzo journalism.

Famously modest and self-deprecating, Moyers often invoked his humble small-town roots. But that did not hide his ambition. His Rolodex was once said to “contain the names of every important person who ever lived,” according to the Times, yet he emphasized the importance of speaking to, for and about “regular people.” He could draw anyone out — from psychiatric patients to Supreme Court justices.

But he resisted opening up about himself, according to the Times. He occasionally spoke about his Johnson years, but he never consented to be interviewed by Robert A. Caro, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer who has spent more than 40 years on his five-volume biography of Johnson. This is likely because of the disagreement between Moyers and Johnson on escalating the war in Vietnam. He must have vowed never to talk about it.

“By all accounts, despite his soft, East Texas style, he is one of the most complicated men that politics or the media ever produced,” the journalist Ann Crittenden wrote in a 1981 profile for Channels magazine titled “The Perplexing Mr. Moyers.”

His Baptist parents had hoped that he would become a minister. “Our parents wanted so deeply for us to make some kind of mark,” Moyers’s brother, James, once said. But Moyers took a different path, and became far more famous and important in the world at large – not a big fish in a small pond, so to speak, but a big fish in a big pond.

He majored in journalism at North Texas State College in Denton, where he was elected class president two years running. In his second year, he wrote to Lyndon Johnson, then the majority leader of the United States Senate, and landed a summer job as an assistant on his 1954 campaign. Johnson persuaded Moyers to transfer to the University of Texas at Austin and take a job at a radio station owned by Johnson’s wife, Lady Bird. Moyers graduated in 1956 with honors, the year before I was born.

After studying religious history on a fellowship at the University of Edinburgh Scotland, he spent two years at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, preaching on weekends. At 25, he was an ordained minister. Then Moyers accepted a job teaching Christian ethics at Baylor University in Waco, but changed his plans after Johnson asked him to be his personal assistant on his 1960 campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination.

He then became Johnson’s executive assistant, and he seemed to be running the campaign. But after Johnson lost the nomination to Kennedy and became his running mate and was elected vice president, Moyers asked to resign to work on plans for the Peace Corps, a new Kennedy initiative. James H. Rowe Jr., a Johnson friend, in a letter to the Peace Corps director, Sargent Shriver, praised Moyers as “that curious and very rare blend of idealist-operator.”

Moyers supervised the drafting of the legislation that created the Peace Corps, then squired Shriver around Capitol Hill, persuading skeptical members of Congress to pass it. He designed the agency’s recruiting, community relations and congressional relations programs. At 28, he became the second in command of the Peace Corps, doing work that he later said was the most satisfying of his life — developing “an idealistic dream” into “an effective program.”

On Nov. 22, 1963, he was in Austin, Texas, when he heard that President Kennedy had been shot. He chartered a plane to Dallas, where he learned that Johnson was on Air Force One. Stopped by a security agent at the stateroom door, he wrote a note to Johnson: “I’m here if you need me.”

He flew back to Washington with Johnson. “I’m just here helping a friend,” he professed to a reporter that week, “and when that ends, I’ll drift away and never be heard of again.” But of course that was not to be the case.

He worked with Kennedy’s speechwriter Ted Sorensen to craft Johnson’s first statements to the country, and became the link between the Johnson and Kennedy circles. As the Johnson era began, Moyers’ familiarity with the bureaucracy helped him organize and guide the 14 task forces of government officials and outside experts that produced most of the Great Society domestic legislation.

His Great Society role was what one friend called his “finest hour.” He overcame the doubts of East Coast intellectuals about Johnson, melded that group with the best of the federal bureaucracy, and enabled continuing communication with the academic community as well. As Patrick Anderson noted in his book The President’s Men published in 1968, he made sure that the process produced “a coherent program flowing from a central philosophy.”

During the 1964 presidential campaign, when Johnson faced conservative Senator and Republican nominee Barry Goldwater in the general election, Moyers oversaw the creation of one of the most notorious attack ads in American political and media history, the “Daisy Girl” commercial. It features a young girl plucking petals from a daisy as the sound of her counting dissolved into the sound of a countdown and images of a nuclear explosion fill the screen, with Johnson’s voice saying, “We must either love each other or we must die.” It is now preserved in the Library of Congress and is available on YouTube.

The commercial, implying that Goldwater could not be trusted with the country’s nuclear arsenal in an international crisis, was widely criticized and pulled from the air after a single showing. But many believed the damage had been done: Its impact was magnified by news coverage and commentary about it in the weeks and months that followed.

In July 1965, with the escalation of American military involvement in Vietnam underway and Johnson’s relationship with the press deteriorating, the president added the job of press secretary to Moyers’s responsibilities. Many in the news media were impressed.

Tom Wicker, the New York Times’s Washington bureau chief, called Moyers “the most able and influential presidential assistant I have ever seen or read about.” Writing in The Washington Monthly in 1974, James Fallows said that Moyers, “intentionally or not,” had “helped to postpone the tide of criticism which finally drove Johnson out of office.”

Moyers resigned in late 1966, citing family obligations, although it was said his admiring notices had begun to wear on the president, and he had been denied two foreign policy jobs that he reportedly wanted. He also most certainly joined Jack Valenti in the administration urging Johnson to reconsider escalating Kennedy’s war in Vietnam, although he did not speak publicly about that.

In 1967, he became publisher of Newsday, the Long Island daily newspaper. He strengthened the paper’s Washington coverage, added international bureaus and hired Saul Bellow to cover the 1967 Mideast war. The paper won two Pulitzer Prizes during his tenure. But its conservative owner, Harry F. Guggenheim, said to be annoyed by the “left wingers” running the paper, sold his majority share in 1970, having turned down a higher offer from Moyers himself, who resigned.

At the suggestion of friends, Moyers embarked on a 13,000-mile bus trip, a tape recorder and a notebook in hand, “to hear people speak for themselves,” as he put it. The dispatch that resulted — a rumination on race, economic power, police-community relations, health care, the environment, unemployment, the media — filled almost an entire issue of Harper’s magazine, then edited by Southern writer and editor Willy Morris from Mississippi. Drawing on that article, he wrote Listening to America: A Traveler Rediscovers His Country, published in 1971, the first of many best-selling books.

Moyers turned down offers to edit newspapers, run colleges and co-host the “Today” show on NBC. “I just didn’t like the idea of selling dog food in a world where so many people were eating it,” he told People magazine. Instead, he began producing a weekly public affairs program on PBS, devoting entire shows to topics like the Watergate scandal and public education. John J. O’Connor of The Times called his show, “Bill Moyers Journal,” “one of the most outstanding series on television.”

In 1976, said to be frustrated by the limited resources in public television, Moyers joined CBS, the top commercial network then, as chief correspondent for the documentary program “CBS Reports.” He produced documentaries on subjects ranging from arson in the South Bronx to the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. But he objected to the show’s irregular schedule: To have more impact, he said, the documentaries needed to appear more often, with more promotion and in better time slots. Rebuffed, he returned to PBS.

Three years later, he was back at CBS, this time as the commentator on the evening news, with something close to a promise of a public affairs program of his own. When he found himself steered onto shows that he considered shallow and commercial, he left again.

“The line between entertainment and news was steadily blurred,” Moyers told a reporter for Newsweek magazine. “Our center of gravity shifted from the standards and practices of the news business to show business.”

He returned once again to PBS with $15 million in grants and his own production company, Public Affairs Television. His wife, Judith Davidson Moyers, whom he had met in his freshman year in college and married in 1954, became president of the company in 1988 and was executive producer of many of his documentaries.

She survives him. In addition to her and his son William, Moyers is survived by two other children, Suzanne and John Moyers; six grandchildren; and one great-grandchild.

Moyers’s six hourlong interviews with Joseph Campbell, who died in 1987, shortly before they aired, were among the first productions made by the new company. Tens of thousands of videotapes of the interviews were sold, and viewers formed study groups to watch them. A companion book — championed by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who was then an editor at Doubleday — became a best seller, as did earlier books by Campbell.

Between the late 1980s and 2007, Moyers and Public Affairs Television turned out nearly 100 documentaries and reports. The subject of one five-part series in 1998 was addiction, a problem with which the Moyers’ eldest son, William, had struggled. “Bill Moyers Journal” returned to the air from 2007 to 2010, starting with an investigation of the shortcomings of the news media in the run-up to the war in Iraq.

In 2012, when he was in his late 70s, Moyers launched an hourlong weekly interview show, “Moyers & Company,” with funding from major foundations, including the Ford Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation. The show aired on public television and radio stations nationwide.

Eight years earlier, Moyers had seemed for a moment to be retiring. Journalists had stopped by to write about the final episode of “Now,” the weekly PBS newsmagazine show that he had hosted for two years. Emerging from the editing room to speak to a reporter, he said, “Maybe finally I’ve broken the habit.”

Apparently, he hadn’t. He finally retired in January 2015 at the age of 80, probably because he too saw the country changing irreparably in the wrong direction as Donald Trump emerged as the front runner in the Republican primary field for president. Who wants to live in a world with a mob boss, conman grifter like Trump running his corrupt businesses from the damn White House like some kind of mad king?

Related: What Will the Mad King Fuck Up Next?

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal.