“We are all captives of the picture in our head – our belief that the world we have experienced is the world that really exists.”

– Walter Lippmann

The Big Picture –

By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. — What image pops into your head when you see or hear someone say, “That’s cool, man?”

As someone who has been “cool” in my own way at least since the early 1970s, I have opinions about what makes something cool. My first awareness of a state of coolness probably dates back to about May of 1972, when Alice Cooper released “School’s Out” for summer, a hit song that reached No. 7 on the Billboard chart.

The 1960s really did come to the South and Alabama in the ’70s. I started learning to play the drums in junior high band. That was 1971. By high school, as a member of the drum line in the marching band, we were no doubt the “coolest” people on campus. We had way more fun than members of the football team. We considered them mostly dumb, redneck jocks. Our majorettes in the band were way cooler than cheerleaders. By the summer of 1973, I had a Ludwig drum set and invited some musicians over to my house to start a rock band. We grew our hair out long, went to rock concerts, and started playing gigs in skating rings for $75 a night. We drank beer and, eventually, smoked weed, and chased girls, or dated as one might say in polite society. Not that polite society was cool. It was not.

In the 1980s, I transitioned from rock clubs to newsrooms, and being a newspaper reporter was pretty damn cool. By the late 1980s, I opened my own business on the Southside of Birmingham and started free-lance writing for magazines. In the 1990s, I taught journalism, and the coolest thing in those days were the colorful Apple computers. “The Big Lebowski” movie was released in 1998. The Dude became the official definition of cool.

Back in 2005, when digital photography first started getting good, I thought it was cool when I started taking pictures of birds and publishing them on the web. That was before Facebook. Now everybody seems to be doing it. On Facebook. By June of 2007, the first iPhone was released – arguably the coolest technology ever.

In 2014 we launched the New American Journal and I remodeled a Roaktrek camper van into a media van and started posting pictures and stories in Washington, D.C. I thought this was about the coolest thing I had ever done, covering politics in the nation’s capital, the most important and powerful city in the world.

I thought other people would think it was cool too.

Read more about it in my memoir: Jump On The Bus: Make Democracy Work Again

But traveling around the country in an RV and living mostly outdoors in campgrounds didn’t really become cool until the coronavirus global pandemic hit in 2020 and the movie “Nomadland” won the Academy Award for Best Picture in April, 2021.

Now everybody who is anybody seems to be doing it.

Well, maybe not everybody. But there’s no doubt the mobile lifestyle caught on. If you happen to visit a national park or any kind of campground, notice all the vans. There are still people traveling in pickup trucks pulling trailers, and plenty of people still just drive a Subaru and popup a tent. But the vans seem to be taking over.

I have a trip planned out west for next year, hopefully, when I will develop my final cool stories about finding diamonds in the U.S., train rides up tall mountains, Earthship houses, Saloon brothels and Sequoia and Redwood forests.

While there are some group level society-wide definitions of what makes something cool, there’s plenty of room for individualism American style. Everybody probably has pictures in their heads about what they think is cool.

One of the coolest things I learned in graduate school was how people form opinions based on “pictures in their heads.” Of course how those pictures formed has changed a lot since Walter Lippmann published the book Public Opinion in 1922. He discusses the pictures in our heads, and established some of our first impressions about “stereotypes” and propaganda, based on what the Germans started doing manipulating people with misinformation during World War I.

The latest “thing” considered cool at least by computer hackers and programmers is Artificial Intelligence or Machine Learning.

I’m not so sure it is too cool, as it is the next big thing that threatens to put even more journalists out of work, which in turn could be a threat to democracy itself. Maybe it could be used to fight global warming and climate change, but so far it seems to be more like the latest technology game or toy as anything else.

As an experiment, I asked Google’s “Bard” to answer the question.

“What’s considered ‘cool’ in the U.S. and how has that changed over time?”

Here’s Robot Bard’s answer. See how you like it. There’s a more academic article below for comparison’s sake. For the record, clearly the academic article is way cooler.

Bard the Robot: What is considered “cool” in the United States has changed over time, reflecting the changing values and interests of American society.

In the early 20th century, coolness was often associated with wealth, status, and sophistication. This was reflected in the popularity of things like fancy clothes, expensive cars, and high-society events.

In the 1950s and 1960s, coolness became more associated with youth, rebellion, and individuality. This was reflected in the popularity of things like rock and roll music, leather jackets, and motorcycles.

In the 1970s and 1980s, coolness became more associated with self-expression, authenticity, and social consciousness. This was reflected in the popularity of things like punk rock music, grunge fashion, and environmental activism.

In the 1990s and 2000s, coolness became more associated with technology, pop culture, and consumerism. This was reflected in the popularity of things like video games, hip hop music, and designer clothing.

In the 2010s and 2020s, coolness has become more associated with diversity, inclusion, and sustainability. This is reflected in the popularity of things like social justice movements, gender-neutral fashion, and plant-based diets.

Here are some specific examples of what has been considered “cool” in the United States at different points in time:

Early 20th century: Wealthy socialites like the Vanderbilts and Astors were considered cool, as were their lavish lifestyles and expensive possessions.

1950s: Greaser culture was cool, with its focus on cars, motorcycles, and rock and roll music.

1960s: Hippies were cool, with their emphasis on peace, love, and social justice.

1970s: Punk rockers were cool, with their rebellious attitudes and DIY fashion.

1980s: Preppies were cool, with their designer clothes and privileged upbringings.

1990s: Grunge musicians were cool, with their flannel shirts, ripped jeans, and angst-filled music.

2000s: Hip hop artists were cool, with their bling-bling jewelry and expensive cars.

2010s and 2020s: Social media influencers are cool, with their perfectly curated feeds and carefully crafted image.Of course, what is considered “cool” is subjective and varies from person to person. But these examples give a general sense of how coolness has changed in the United States over time.

A friend and partner posed the question for another ML or AI program, ChatGPT. Here’s what Robot ChatGPT had so say.

“Cool” in the U.S. is often associated with trends, fashion, and attitudes. Over time, it has evolved from the rebellious spirit of the 1950s to various subcultures like the counterculture movement in the ’60s, the hip-hop scene in the ’80s, and the tech-savvy culture today. It’s dynamic and influenced by music, movies, and societal shifts.

If you do a simple web search for the same terms, you will find this article, which I think is pretty cool, from the website of the World War II Museum. It’s more of an academic article.

The Origins of “Cool” in Post-WWII America

Miles Davis, Howard McGhee, and unknown pianist. NYC, September 1947. Photography by William P. Gottlieb. Courtesy of the Library of Congress: NAJ screen shot

The modern usage of the word “cool†surfaced during World War II. Cool was a new concept, a new set of encoded ideas, and a new musical aesthetic. An icon of cool is a person who has created or inspired social change through art, protest, or popular culture.

Black jazz musicians disseminated cool in the 1940s, and for about a decade, only fans and musicians used the term. Yet, its many phrases caught on quickly, first on the streets, and later, among Beat writers and Bohemians: be cool, playing it cool, “Cool it!†Like most new slang, its meanings were at first understood only in context. In effect, you had to be “cool†just to know what “cool†meant. This ambiguity was part of cool’s mysterious power.

The jazz saxophonist Lester Young, the star soloist of the Count Basie Orchestra, was the first to say “I’m cool†in reference to a state of mind: it meant he felt relaxed, safe, and laid-back in the environment. Young’s use of the phrase also encoded a certain protest during the Jim Crow era of racial segregation: “I’m cool†meant “I’m keeping it together—in mind and spirit—against oppressive social forces.†Cool had come into common use among Black Americans in the 1930s as a term for calming someone down from emotional stress.

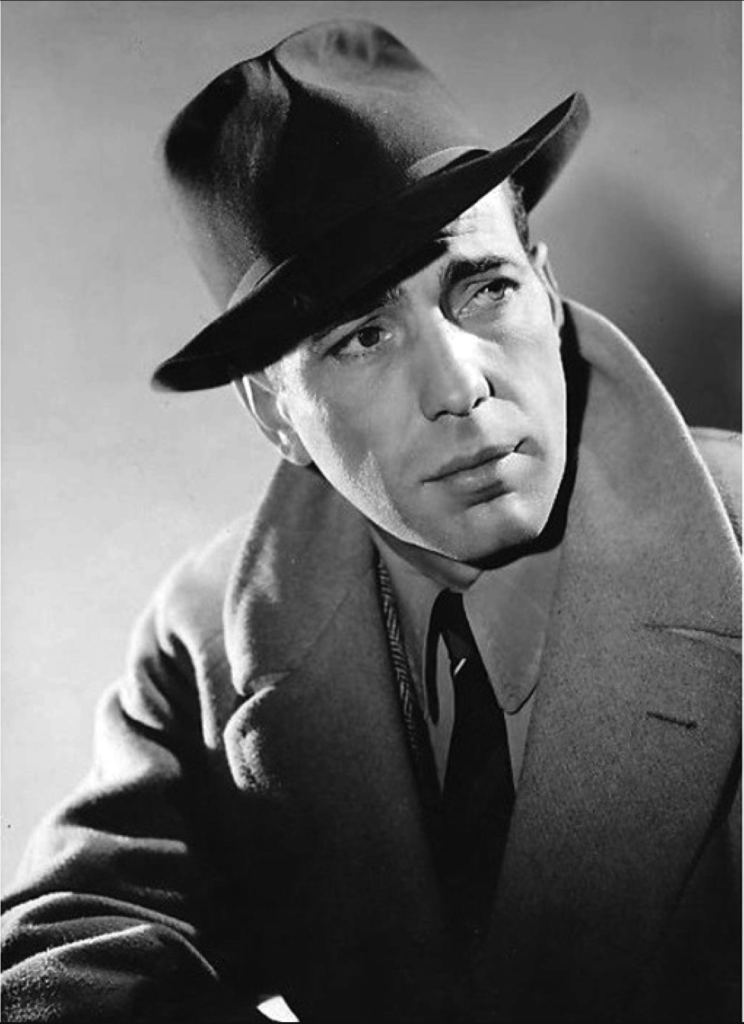

As Big Bill Broonzy sang to a woman in “Let Me Dig It†(1938), “Let me cool you, baby / before the ice man come.†Young redirected “cool†to stand for a calm emotional state and a balanced mind. In The Jazz Lexicon, the dictionary of jazz musicians’ slang, “cool†was defined as “the linguistic parallel of the new post-World War II musical temper (more relaxed, cerebral, sophisticated).†In effect, cool was an ideal state of emotional self-control, analogous to the unruffled stoicism of such actors as Humphrey Bogart or Robert Mitchum.

Humphrey Bogart in 1940. Published by The Minneapolis Tribune, photo from Warner Bros, retrieved via Wikimedia Commons: NAJ screen shot

Jazz songs invoking cool for a certain stylish stoicism first began to appear at the beginning of World War II. Erskine Hawkins’s hit, “Keep Cool, Fool†(1940), was a humorous song advising listeners to keep their own counsel. Young’s own “Just Coolin’” (1945)—meaning just relaxing, or “just chillin’”—came out in 1945. The following year, there were three compositions invoking Young’s ideal state: Count Basie’s “Stay Cool†(1946), Fats Navarro’s “Everything’s Cool†(1946), and Charlie Parker’s “Cool Blues†(1946). The latter received France’s Grand Prix du Disque award (best record) for 1946.

To novelist Ralph Ellison, cool was a quality of Black survival and resistance: it combined “resistance to provocation†with “coolness under pressure†in the ongoing struggle for freedom and social quality. Given the strict racial segregation of most of US life, including all of the branches of the armed forces, keeping it together was no small matter for Black Americans. The daily stress of systemic racism led to this value of “coolness†as a coded term for defying racism and trying to survive-with-dignity.

In addition, “hot music†and “hot jazz†were common synonyms for the genre until 1947, with “hot†meaning emotional or exciting. The star soloist in a big band was known as its “hot man,†the musician known for exciting audiences with virtuosic runs or brilliant solos. Jazz was known as Le Jazz Hot in France and “hot jazz†in Germany. The first studies of jazz were Hot Jazz: The Guide to Swing Music (1936) and Jazzmen: The Story of Hot Jazz Told By the Men Who Created It (1939); Esquire magazine, a key mainstream node of jazz, released an annual set of records called Esquire’s All American Hot Jazz.

In his memoir Really the Blues (1946), the Jewish clarinetist Mezz Mezzrow recalled the hostility of jazz musicians towards fans who stood under the band yelling, “Get hot! Get hot!†This action fed into two common racist stereotypes of Black men: first, that jazz musicians were entertainers rather than artists, like classical musicians; second, that jazz was just a natural outpouring of emotions. Significantly, to be emotionally “hot†(or excited) is the opposite of being “cool†(calm and in control).

The new stoicism of black cool was a form of in-group solidarity. Black musicians refused to smile on-stage, choosing to “cool†the face into a blank mask while playing innovative, difficult music. In addition, jazz musicians created their own jargon (then called “jiveâ€) to encode their thoughts, insulating their anger from the systemic racism of the police. To name just a few examples from the New York Police Department (NYPD) in the 1950s: Miles Davis was arrested for helping a white woman into her car at the club Birdland, under a marquee with his own name on it; the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Harry Anslinger, held a personal vendetta against Billie Holiday for her nonviolent drug use; the NYPD regularly suspended a jazz musician’s cabaret card for any infraction, removing their ability to play clubs and earn a living, a form of economic terrorism.

How would one survive this kind of oppression—in a country calling itself “the home of the freeâ€â€”without blowing one’s top? A person would have to be “cool.â€

In effect, the “hot man†became “the cool man†after the war; in addition, “cool†became a call to individuality. In the post-war jazz idiom of bebop, musicians made the creation of an individual voice—a signature sound—the art form’s highest value. Denied a voice in US society, jazz musicians asserted their individuality through a personalized sound.

Jazz was the dominant subculture of the post-war era, and its influential slang was cool’s first rebel code. In effect, cool was a password for an unstated code of ethics; when it crossed over in New York’s jazz clubs, every Beat Generation writer noticed. Jack Kerouac wrote a letter to Neal Cassady to explain his new “theory of cool†in 1950. In the first Beat novel, Go (1952), John Clellon Holmes identified cool as the symbolic word of the post-war mood: it meant “pleasant, somewhat meditative, and without tensionâ€; young people were acting “cool, unemotional, withdrawn.†Within a few years, the phrase “play it cool†— meaning, keep your emotions suppressed—appeared in hit songs by Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra, and Elvis Presley.

Yet, the ethos of cool also has roots in West African cultures, where it is called itutu, or “spiritual balance,†among the Yoruba. Many African languages have a similar term, with “cool†as the literal translation of unusual calmness: to have this quality is to be known as a peacemaker, as a person able to “cool out†a situation, as a person who keeps his or her own counsel. In addition, “cool rhythms†are central to West African drumming practices. “Cool rhythms†are relaxed, steady, and supportive; “hot rhythms,†in contrast, are aggressive, heated, and propulsive. The African historian Robert Farris Thompson has designated cool as “the fundamental trope of African America.†So when jazz bassist Esperanza Spalding played the White House in 2016, she simply stated, “Jazz is urban cool.â€

COLD WAR, COOL AESTHETIC

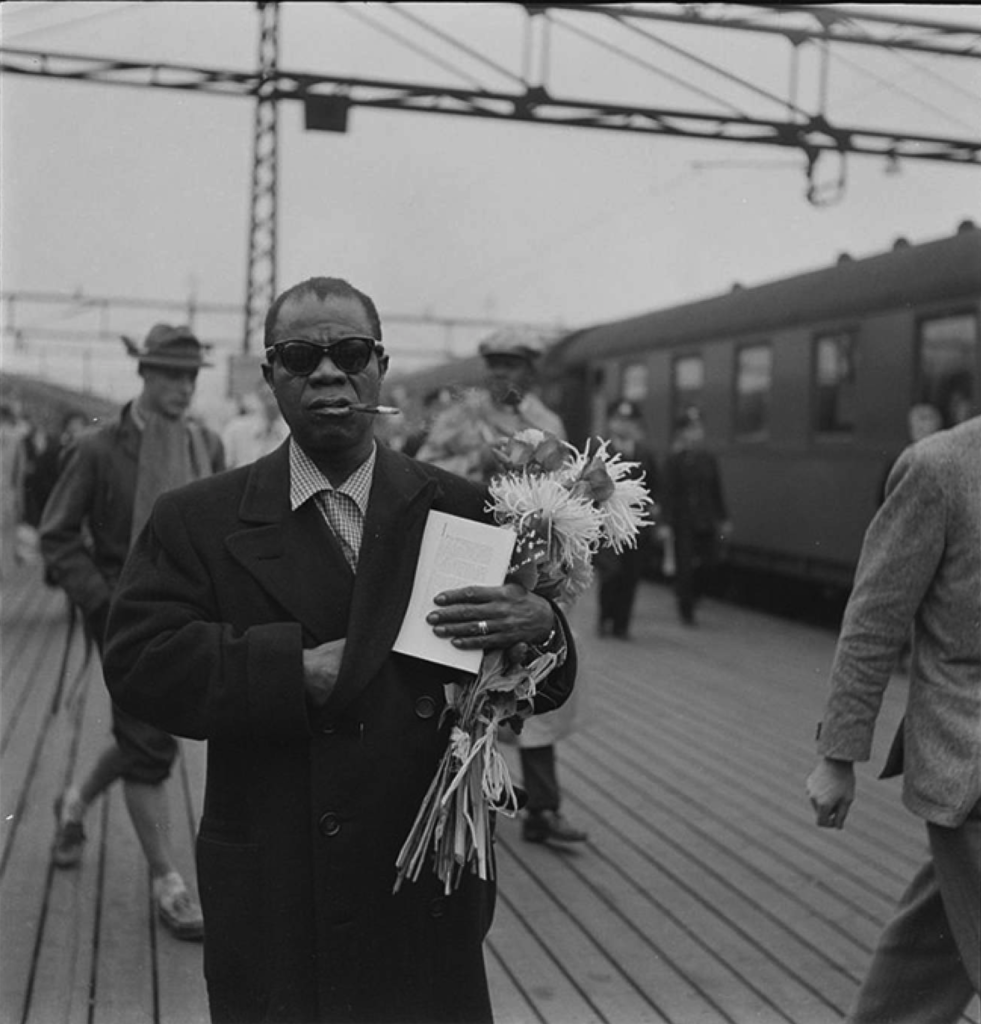

Louis Armstrong on his way to a concert in Oslo, Norway in 1955. Courtesy of the National Archives of Norway, retrieved via Wikimedia Commons: NAJ screen shot

“Jazz turned the Cold War into a cool war,†wrote the German historian Reinhold Wagnleitner. Both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany banned jazz: neither Nazism nor Communism could tolerate a music that encouraged finding one’s individual voice within an ensemble setting. “Jazz is democracy,†Wynton Marsalis often declares today, referring to the genre’s combination of individual freedom and ensemble interplay, yet this framework was first theorized by two American scholars in 1947.

Still, it was European writers who cemented the association of jazz with “freedom of expression,†having picked it up from Duke Ellington’s famous declaration, “If jazz means anything, it is freedom of expression.†In post-war Paris, the sound of liberation after the Nazi occupation was New Orleans jazz. Simone de Beauvoir, the existentialist philosopher, reported that Louis Armstrong’s performance in 1946 made “the youth mad with enthusiasm.†In novels and essays, Josef Skvorecky wrote about the liberating feeling of jazz under Nazi and Soviet-backed regimes, even documenting Nazi prohibitions of “Judeo-Negroid excesses in tempo or in solo performances.â€

Jazz cool was the American version of existential freedom called for by the French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir. Jazz producer Ross Russell called jazz musicians “America’s organic existentialists.†“Jazz cool†concerned the recuperation of individuality in the arts against the century’s totalitarian ideologies. And the embodiment of “cool†was the improvising jazz musician, creating and re-creating his individual voice nightly.

Along with “jazz cool†there was also a subgenre called “cool jazz,†a romantic melodic sensibility that valued restraint, flow, and self-expression over sonic power, rhythmic emphasis, and even virtuosity. Lester Young and Billie Holiday pioneered the minimalist power of cool understatement, by accenting only certain words or notes through rhythmic nuance and a sophisticated manipulation of musical space. In essence, the “cool aesthetic†favored fewer notes timed for affect and effect. French existential writer Boris Vian heard it most in Miles Davis’s muted trumpet solos, as they seemed to float apart from the band, as if played by “somebody who is part of the century but who can look at it with serenity.†The genre found its name in Miles Davis’s album, Birth of the Cool (1957).

In the early 1950s, Frank Sinatra re-tooled jazz’s cool aesthetic into a global style. He adapted from Holiday her artistic genius in narrating songs as if they were short stories. Sinatra and Young “had a mutual admiration society,†he recalled. “I knew Lester well. We were close friends… I took from what he did, and he took from what I did.†As Young once said in an interview, “If I could put together exactly the kind of band I wanted, Frank Sinatra would be the singer.†By 1955, the word and aesthetic were so evocative that June Christy had a hit with “Something Cool,†with its tagline, “I’d like something cool.â€

THE LEGACY OF COOL REBELLION

For his oral history, The Birth of The Cool: Bebop, The Beats, and the American Avant-Garde, poet Lewis MacAdams interviewed many of the musicians, writers, and artists who made the post-war scene in Greenwich Village, New York City. Born and raised in Dallas, MacAdams recalled the first time he heard the word “cool†on a rhythm-and-blues radio show in 1952.”

“What did I mean, then, when I thought that the Beats were cool?†he reflected. “I had no idea. I just liked the feeling when I said the word.â€

He later unraveled cool’s evocative allure.

“’Cool’ meant not only approval, but kinship. It was a ticket out of the life I felt closing in all around me; it meant the path to a cooler world.â€

For him, a “cooler world†referred to a floating community of kindred spirits interested in self-liberation and artistic innovation.

When White jazz fans brought cool into national awareness, the concept carried over qualities such as authenticity, innovation, intelligence, and tolerance. For MacAdams, a trio of young artists’ deaths—actor James Dean, saxophonist Charlie Parker, and painter Jackson Pollock—triggered “the age of cool.†Beat poet Gary Snyder soon defined cool among San Francisco Bohemians as “our ongoing in-house sense of [being] detached, ironic, hip, with an outlaw/anarchist edge.†By the mid-1960s, Ken Kesey often referred to the Merry Pranksters’ iconic cross-country road trip as “the search for a kool place.â€

Cool is a symbolic word that emerged in the post-war era as an emblem of social and cultural resistance against defenders of the status quo and social norms, people considered uncool almost by definition. Jazz musicians became symbols of freedom, agency, and possibility for writers, painters, and musicians around the world.

Cool is a word, concept, and streetwise philosophy born in post-war jazz culture, and its legacy is its global ubiquity. Everyone still wants to be cool, both in the sense of being relaxed (chill) and in leading the charge for social change. To refer to someone as cool means that person has created an edge to walk all their own.

About the Author

Joel Dinerstein is the author of several works on the history of cool, including The Origins of Cool in Postwar America (University of Chicago, May 2017), Coach: A Study of New York Cool (Rizzoli 2016), and American Cool (2014). He was the co-curator of American Cool (2014), an acclaimed photography and cultural history exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian based on his own research and theories. He is also the author of an award-winning cultural history of jazz and industrialization, Swinging the Machine: Modernity, Technology, and African-American Culture (2003), as well as several articles on American identity and popular culture (e.g., film noir, jazz, literature, technology, sports, rock-and-roll). He has served as a consultant for popular music and jazz for Putumayo Records, HBO’s Boardwalk Empire, and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). He has received the Student Body Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching and teaches courses at the intersection of modernism, popular culture, African-American Studies, and contemporary literature. He was a jazz DJ for seven years on WWOZ-FM in New Orleans and also teaches courses on blues, jazz, and New Orleans musical culture. He has written several insider articles about New Orleans second-line culture as a member of the Prince of Wales club. He has a PhD in American Studies from the University of Texas (Austin) and was educated exclusively at public schools.

So which version do you like best or trust more?

In Lippmann’s introduction to his book, he quotes The Republic of Plato, Book Seven, the story of Plato’s Cave.

The first chapter title is ‘The World outside and the Pictures in our heads,’ introducing his conception of the ‘stereotype’. This explained how public opinion was formed and manipulated because of what we trust as an ‘authentic messenger’. Lippmann had worked with the CREEL Committee that influenced public opinion by censoring information that was anti-war and producing thousands of pro-war pamphlets, cartoons, magazines, and movies so that the USA could enter the World War in 1917 after stating it would not.

Lippmann tried to explain how the pictures that arise spontaneously in people’s minds come to be—a simplification of his theory is that we live in second-hand worlds. Because we are aware of much more than we have personally experienced our own experience is mainly indirect. Lippmann felt that the only feeling that anyone can have about an event, that they did not experience, is the feeling aroused by their mental image of that event.

But in his day, radio was new, and there was no television, certainly no internet or social media. Television quickly became the vehicle to put pictures in peoples’ heads.

Now Facebook pics, selfies and memes seem to be the thing.

How cool is it? I’ve been skeptical from the start in 2008.

What’s next?

I wish I knew. But I’m slowing down and growing a bit tired of always being ahead of my time in the coolness department. I hope the kids know what they’re doing. It doesn’t look like it, at least according to the pictures in my head. Good luck.

I think this is a pretty cool picture. Guess it’s not hot guys and girls twerking on TikTok. Sorry.

#Codger Power – Glynn Wilson on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol Building in the Spring of 2022 with the cherry blossoms in full bloom: Brooks Boliek

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal. We just tell it like it is, no sensational clickbait or pretentious BS.