By Glynn Wilson –

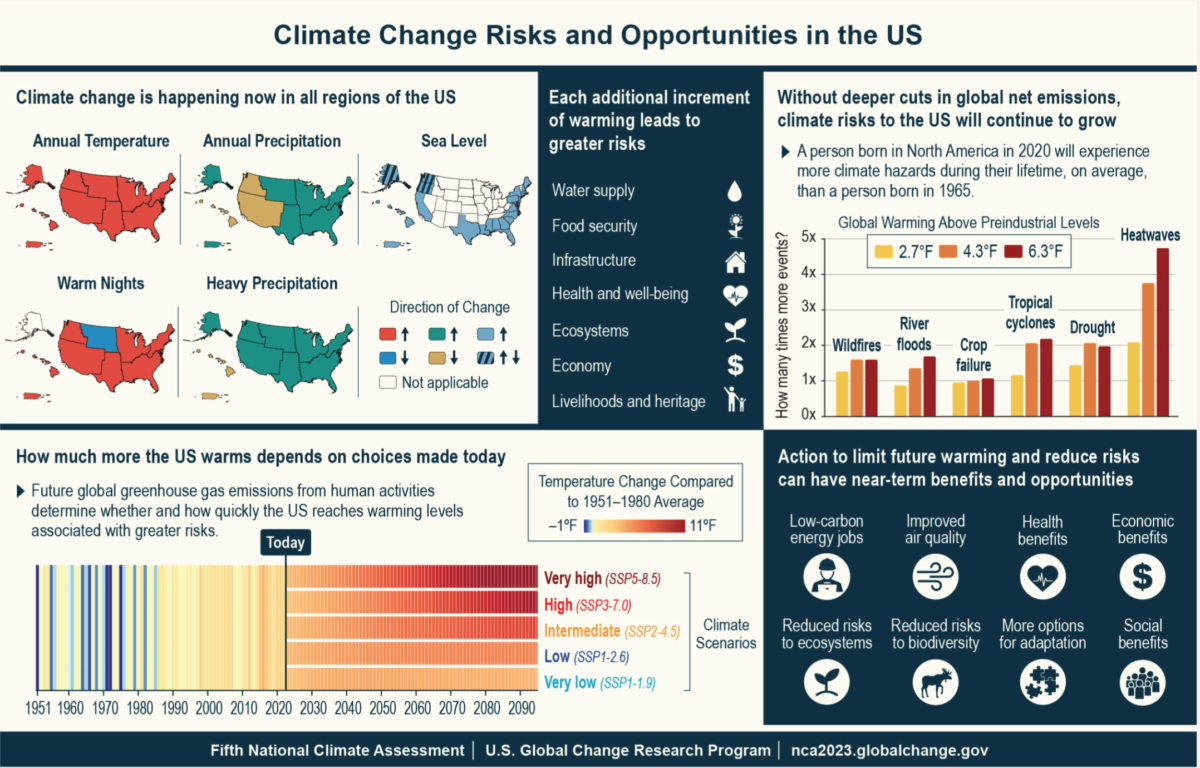

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Massive changes in the climate due to global warming from the burning of fossil fuels for energy and transportation is deadly and expensive, but some of the most extreme impacts could be prevented if there was the political will to take on the challenges, according to the new National Climate Assessment, the most sweeping, sophisticated federal analysis of climate change compiled to date.

Released every five years, the National Climate Assessment is a congressionally mandated evaluation of the effects of climate change on American life. This new fifth edition paints a picture of a nation beset by climate-driven disasters, yet capable of dramatically reducing emissions of planet-warming gasses if only policy makers could agree to acknowledge the science and lead the public to go along with required changes in lifestyle choices.

This is the first time the assessment includes stand alone chapters about climate change’s toll on the American economy, as well as the complex social factors driving climate change and the nation’s responses. And, unlike past installments, the new assessment draws heavily from social science, including history, sociology, philosophy and Indigenous studies. The new approach adds context and relevance to the assessment’s robust scientific findings, and underscores the disproportionate danger that climate change poses to poor people, marginalized communities, older Americans and those who work outdoors.

“Climate change affects us all, but it doesn’t affect us all equally,” says climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe, one of the authors of the assessment. But threaded throughout the report are case studies and research summaries highlighting ways “climate action can create a more resilient and just country,” she says.

This is also the first time the National Climate Assessment will be translated into Spanish, NPR points out in its coverage, although the Spanish-language version won’t be available until the spring, according to the White House.

The National Climate Assessment is extremely influential in legal and policy circles, and affects everything from court cases about who should foot the bill for wildfire damage, to local decisions about how tall to build coastal flood barriers.

“It really shapes the way that people understand, and therefore act, in relation to climate change,” says Michael Burger, the director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University.

Hundreds of scientists from universities, industry, and federal agencies contributed to the report. They reviewed cutting-edge research published since the last report and contextualized it in decades of foundational climate research. The fifth edition of the assessment arrives as millions of Americans are struggling with the effects of a hotter Earth. Dramatic and deadly wildfires, floods and heat waves killed hundreds of people in the United States in 2023.

And, while federal spending on renewable energy and disaster preparedness has increased due to the priorities of the Biden administration, the U.S. is also investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure that is not compatible with avoiding catastrophic warming later this century.

In addition, things would get much worse if the country were to return to electing global warming and climate change deniers such as Donald Trump.

More Expensive Lives

Climate change makes life more expensive, according to the report, including food, housing and labor.

Climate-driven weather disasters, like heat waves, floods, hurricanes and wildfires, are particularly expensive, the report points out in detail. These disasters destroy homes and businesses, wreck crops and create supply shortages by delaying trucks, ships and trains from moving goods to market. Such disasters make it more likely that families will go bankrupt, and that municipal governments will run deficits.

Weather-related disasters in the U.S. cause about $150 billion each year in direct losses, according to the report.

“That’s a lot of money – roughly equal to the annual budget for the Energy Department – and it’s only expected to go up as the Earth gets hotter,” says NPR.

And that’s all before factoring in the less obvious or tangible costs of climate change. Healthcare bills for people who are sicker because of extreme heat, or have respiratory illness brought on by breathing in mold after a flood, for example. Exposure to wildfire smoke alone costs billions of dollars a year in lost earnings — a burden that falls disproportionately on poor people who work outdoors.

“The research indicates that people who are lower income have more trouble adapting [to climate change], because adaptation comes at a cost,” says Solomon Hsiang, a climate economist at the University of California, Berkeley and a lead author of the assessment.

For example, one of the simplest ways to adapt to severe heat waves is to run your air conditioner more. But “if people can’t pay for it, then [they] can’t protect themselves,” Hsiang says.

And the hotter it gets, the more profound the economic harm. Twice as much planetary warming leads to more than twice as much economic harm, the assessment warns.

Climate Change Causes Sickness and Death

Since the previous report released five years ago, the health costs of climate change have gone from theoretical to personal for many Americans. The most obvious risk is extreme weather, particularly heat, says Mary Hayden, the lead author of the chapter examining human health. Heat waves have become hotter, longer, and more dangerous, and they’re hitting areas that aren’t ready for them–like the “record-shattering” heat dome that descended on the Pacific Northwest in 2021 and caused hundreds of deaths.

Wildfire smoke can send people thousands of miles from the fires to hospitals with respiratory problems and heart disease complications.

Hurricanes can disrupt people’s access to healthcare: when a clinic is flooded or people are displaced, kidney patients can’t get dialysis treatment, for example.

In most cases, the people who bear the brunt of the disasters are those already at risk: poor communities, communities of color, women, people with disabilities and other marginalized groups.

Temperatures in formerly redlined neighborhoods in cities across the country can soar nearly 15 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than wealthier areas just blocks away, putting residents at much higher risk of heat exposure.

The assessment also homes in on research tracking less-obvious health impacts. Living through climate disasters, for example, can leave lasting emotional scars.

“We’re not just talking about [people’s] physical health–we’re talking about their mental health,” Hayden says. “We’re talking about their spiritual health. We’re talking about the health and well-being of communities which are being affected by this.”

That means recognizing the long-term effects on communities like Paradise, California, where people still deal with deep emotional trauma five years after their town burned in the 2018 Camp Fire. The report also flags the growing emotional toll on children and young people, for whom anxiety about the future of the planet is bleeding into all parts of their lives.

Climate Change Threatens Special Places

The places, cultural practices, and traditions that anchor many communities are also in flux because of climate change, according to the report. Fishing communities are seeing their livelihoods shift or collapse. The Northeast’s iconic lobster fishery, the single most economically valuable in the country, has withered as marine heatwaves sweep through the regional seas.

Shrinking snowpack and too-warm temperatures are interrupting opportunities for beloved recreational activities, like skiing or ice fishing.

Indigenous communities are being forced to adjust to new climate realities, which are disrupting traditional food-gathering traditions. In Palau, a monthly tradition of catching fish at a particularly low tide has been upset by sea level rise, which keeps water levels too high to trap fish in the historically-used places. Sea level rise is also forcing coastal communities to re-think their very existence, pulling apart the social fabric that has developed over generations.

But many communities – Indigenous people, farmers and fishers, groups that have lived tightly connected to their environments for a long time – have deep stores of resilience from which to draw, says Elizabeth Marino, a sociologist and the lead author of the chapter on social transformations.

“There is quite a lot of wisdom in place to adapt to and even mitigate climate change,” she says. “It allows people to come up with solutions that fit the lives that they lead, and that’s also a place of hope.”

The fifth assessment lays out a stark picture of the climate challenges the U.S. faces. Keeping planetary warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), the goal of the international Paris Agreement, will require immediate, enormous cuts to fossil fuel emissions in the U.S and beyond. Keeping warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), an ambitious target written into the Agreement, will be even harder, the report says.

But it also points out many successful efforts underway to adapt to the new reality and to prevent worse outcomes.

“It’s not the message that if we don’t hit 1.5 degrees, we’re all going to die,” says Hayhoe. “It’s the message that everything we do matters. Every 10th of a degree of warming we avoid, there’s a benefit to that.”

Addressing fossil fuel-driven climate change can also help people live healthier lives, stresses J. Jason West, the lead author on a chapter on air quality. Dialing back fossil fuel emissions would help prevent further climate change and also lessen the kinds of air pollution most harmful to human health.

“There really is a lot of opportunity to take action that would resolve both of those problems at the same time,” West says.

There’s been a subtle shift in the report’s perspective since the last one, says Candis Callison, a sociologist and author of the report. There’s now a clear acknowledgement, developed through years of rigorous research, that the fossil fuel-powered society the U.S. built over generations was profoundly unjust. Many pollution-producing coal or gas power plants were sited in communities of color rather than white communities, affecting people’s health outcomes for generations. And decisions about land and water use for energy extraction often excluded tribal communities, with consequences still playing out today.

The transition forward can look different, she says.

“Climate change actually provides us with an opportunity to address some of those inequities and injustices–and to respond to these impacts,” Callison says. “That’s really a powerful thing.”

According to the New York Times coverage of the report, nearly every cherished aspect of American life is under growing threat from climate change and it is effectively too late to prevent many of the harms from worsening over the next decade, including the food we eat and the roads we drive on, our very health and safety, as well as cultural heritage, natural environments and the economy.

Global warming caused by human activities — mostly the burning of oil, gas and coal — is raising average temperatures in the United States more quickly than it is across the rest of the planet., according to the report.

“Too many people still think of climate change as an issue that’s distant from us in space or time or relevance,” said Katharine Hayhoe, an atmospheric scientist at Texas Tech University who contributed to the report. The new assessment shows “how climate change is affecting us here, in the places where we live, both now and in the future,” she said.

Human-driven warming is intensifying wildfires in the West, droughts in the Great Plains and heat waves coast to coast. It is causing hurricanes to strengthen more quickly in the Atlantic and loading storms of all kinds with more rain. So far this year, the nation has experienced a record 25 billion-dollar weather disasters, many of them exacerbated by the hotter climate.

Yet Not All Is Lost

Cost-effective tools and technologies to significantly reduce America’s contribution to global warming already exist, the report shows. U.S. emissions of heat-trapping gases fell by 12 percent between 2005 and 2019 as the country has shifted from coal toward natural gas and renewable sources. Options are increasing for electrifying energy use, reducing energy demand and protecting natural carbon sinks like forests and wetlands.

Yet the United States and other industrialized countries are still curbing their emissions so sluggishly that a certain amount of additional greenhouse warming is essentially locked in, forcing societies to learn to live with the effects. Americans’ efforts have mostly been “incremental” instead of “transformative”: installing air-conditioners rather than redesigning buildings, increasing irrigation rather than reimagining how and where crops are grown, elevating homes rather than directing new development away from floodplains.

Americans, the report says, need to make deeper changes to the ways they work, manage their environments and move through them to become resilient to the climate conditions that humanity’s past choices have brought about, conditions that Earth has never before experienced while hosting so many members of our species.

More than 750 experts evaluated thousands of academic studies and other types of knowledge to compile the latest report, which is being issued as world leaders prepare to gather in the United Arab Emirates for annual United Nations climate talks at the end of November.

Federal agencies have produced new assessments twice a decade or so since 2000, as mandated by a 1990 law. After the previous installment was issued in 2018, the Trump administration tried but largely failed to thwart work on the latest one.

The new report is also coming out as President Biden begins his push for re-election, the Times points out. Many young voters who are alarmed by global warming have expressed disapproval of Biden’s decision to greenlight new oil drilling in Alaska, but Biden administration officials said the assessment’s findings showed how the president’s policies were moving the nation toward a clean-energy future.

Biden was expected to announce on Tuesday $6 billion in investments to modernize America’s electric grids and support projects that address the unequal effects of environmental hazards on minority and tribal communities.

“We’ve got climate solutions that can be made in America and are being made in America, that we’re deploying brick by brick and block by block,” said Ali Zaidi, the White House national climate adviser. “That gives us hope.”

Every part of the country is feeling the effects of the warming planet, the report finds. Rising fatalities from extreme heat in the Southwest. Earlier and longer pollen seasons in Texas. Northward expansion of crop pests in the Corn Belt. More damaging hailstorms in Wyoming and Nebraska. Stronger hurricanes in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Shifting ranges for disease-spreading ticks and mosquitoes in many regions.

The latest climate assessment is the first to include a dedicated chapter on economics, reflecting scholars’ growing interest in pinning down both the direct costs of climate change and its wider effects on households, businesses and markets, said Solomon M. Hsiang, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, who helped lead the writing of the chapter.

These effects vary between regions, with hotter ones facing more harm and colder ones potentially benefiting. But the report cites studies showing an overall loss in the nation’s economic well-being. For every 1 degree Fahrenheit that the planet warms, the U.S. economy’s growth each year is 0.13 percentage points slower than it would be otherwise, the report finds, a seemingly small effect that can add up, over decades, to a sizable amount of forgone prosperity.

Such metrics do not, however, capture the full effects of warming on less-tangible things Americans value, including human health, ecosystems, trades like fishing that are passed down over generations and even recreational activities such as skiing, camping and other outdoor pastimes that wildfire smoke and scorching heat increasingly lace with peril.

“Nonmarket effects of climate change in many cases are some of the largest,” Dr. Hsiang said.

Governments do much of the spending to respond and adapt to climate change, and the assessment warns of increased costs of public programs such as disaster aid, wildfire suppression, crop insurance subsidies, endangered species protection and health care. Such expenditures could rise even as climate change undercuts tax revenues by reducing incomes and housing values. Private insurers are already so tired of losing money in catastrophe-prone places like California that they are restricting coverage or pulling out.

The assessment finds that efforts to plan for climate threats have expanded in recent years. Around two in five states and 90 percent of U.S.-based companies have assessed their climate risks. Eighteen states have climate adaptation plans; another six are working on theirs.

So far, though, implementation has been “insufficient,” the report concludes. Funding is a challenge, it says, but so is coordination.

The assessment cites a few programs in California and Florida that have tried to plan for climate adaptation across city and county lines. Yet when not properly designed and monitored, adaptation efforts can lead to unintended side effects, said Katharine J. Mach, an environmental scientist at the University of Miami who contributed to the report.

“In some cases, we may be working well on climate but creating other issues,” she said.

Disaster relief, for example, goes disproportionately to cities and towns, which could be exacerbating urban-rural disparities, Dr. Mach said. Federal buyouts of homes in vulnerable places have occurred disproportionately in wealthy counties, largely because agencies there can better navigate the bureaucratic requirements.

The assessment acknowledges America’s progress toward pumping less carbon into the atmosphere but says the country must do more — and much, much faster. Emissions from generating electricity in the United States are down about 40 percent from 2005. Yet emissions from transportation rose by nearly 25 percent between 1990 and 2018, even as vehicles became more energy efficient. The reason? Americans are driving more.

Achieving the nation’s emissions goals will probably require continued advancement in technologies like hydrogen fuel and carbon dioxide removal, the report says. But it will also involve doing more of the things we can do already, such as generating electricity with clean sources and replacing car engines, furnaces and boilers with electric versions.

“People sometimes focus so much on the stuff that we don’t know how to do that it paralyzes them in thinking about the options that we have today,” said Steven J. Davis, a professor of earth systems science at the University of California, Irvine, and another author of the report.

Still, solar and wind facilities will require enormous amounts of land, potentially 3 to 13 percent of the area of the contiguous United States, the report finds. Around 8 million Americans, or 5 percent of the labor force, work in energy-related jobs, many of which are at risk in the shift to renewable sources. The Biden administration’s plans for offshore wind power have run into trouble as rising interest rates, supply chain delays and local opposition stymie projects.

Dr. Davis expressed optimism that the hurdles could be navigated.

“It’s not all bad trade-offs,” Dr. Davis said.

The assessment cites analyses showing that clean energy and related industries can create enough jobs to offset declines in fossil-fuel employment. Switching to zero-carbon energy could reduce air pollution enough to prevent 200,000 to 2 million deaths by 2050.

But if the country goes back to electing politicians and sending them to Washington who claim they do not “believe” in the science, human life on planet Earth could be threatened within a generation.

USDA

The Department of Agriculture sent out an email update on its contributions to the report on Tuesday.

“Our farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners are on the front lines of climate change. USDA’s role in the NCA5 exemplifies our commitment to supporting these individuals and communities, especially those who are disproportionately affected,” said Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack.

The report, released on November 14, 2023 by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, was developed through a partnership with 14 federal agencies and included 58 USDA scientists. The information and analysis in the report can be used to inform decision-making, but it does not prescribe specific policies or actions.

USDA’s contributions to the NCA5 highlight the effects of climate change on agriculture, forests, food systems, historically underserved communities, and natural resources. The report emphasizes the increasingly important role of adaptation in building resilience, and the role of the land sector in mitigating greenhouse gases. It demonstrates how climate change affects the livelihoods of USDA’s stakeholders and it provides examples of how land managers are changing their operations and practices in response to changing climate conditions.

The effects of climate change are not confined to specific regions; rather, the entire nation is vulnerable to its consequences. Climate-induced changes in productivity, trade infrastructure, and livelihoods affect everyone – U.S. consumers who depend on globally integrated food and forest-product supply chains, international consumers of U.S. products, and U.S. producers whose livelihoods are connected to global food and forest-product supply chains.

USDA recognizes that agriculture and forests have pivotal roles to play in addressing climate change. The report “is a comprehensive and timely evaluation of climate change’s relationships with the land sector,” the agency says. “By understanding climate change and prioritizing innovation, land managers can be more adaptable to changing conditions and working lands can help to lessen the impacts of climate change.”

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal. We just tell it like it is, no sensational clickbait or pretentious BS.