WASHINGTON, D.C. — As wars continue to rage in Israel-Gaza and Russia-Ukraine, and the Republicans still can’t seem to find a Speaker of the House they can get behind, what is the American public paying attention to and concerned about these days?

Judging by what people seem to be interested in liking and sharing on Facebook in this post-Trump and post-Covid world, people are traveling like there’s no tomorrow and sharing their own smart phone pictures of the places they are visiting, especially national parks. People are still interested in what is going to happen to Donald Trump with all the legal cases pending against him in Washington, New York, Georgia and Florida, and social media activity reflects that.

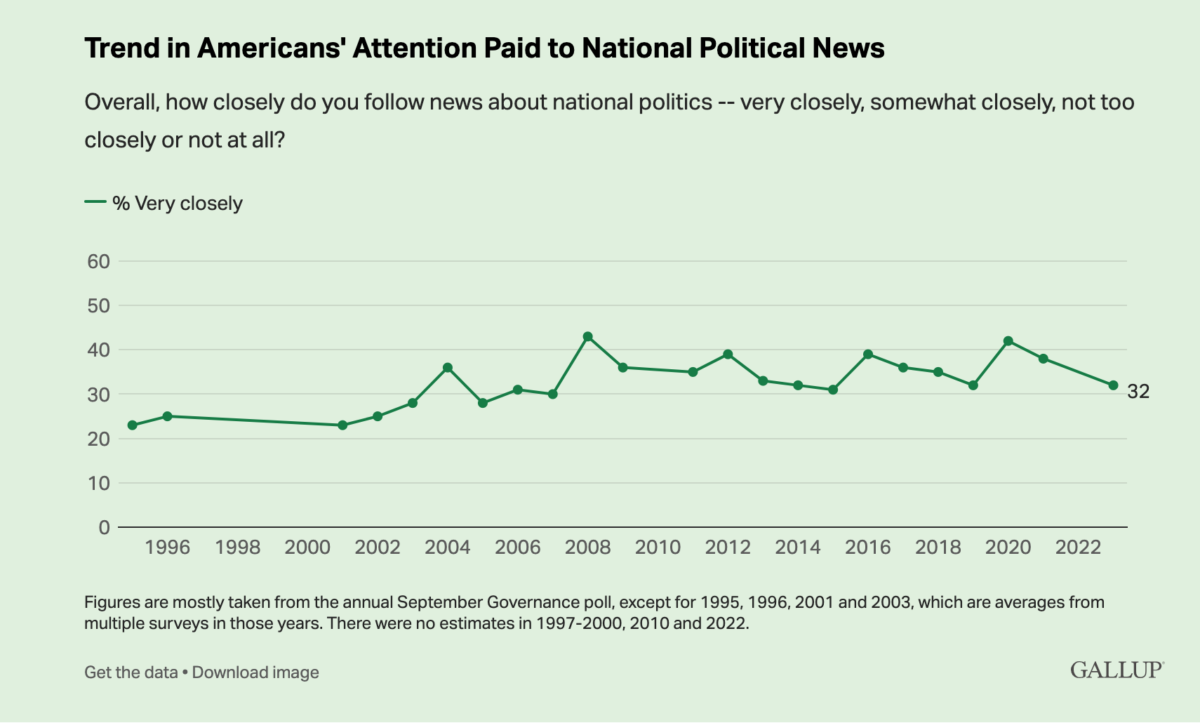

But according to a recent Gallup poll, public interest in political news peaked in 2020, when 42 percent of the American public expressed a heightened interest in following national political news. That number probably shocks those who are highly engaged, realizing that such a huge swath of the American public doesn’t seem to be interested in politics or news about it.

By the spring of 2021, after Democrat Joe Biden was sworn in as president and most people were able to get vaccinated against Covid-19, that number dropped to 38 percent when people needed a break from politics and the news about it. But more concerning, that trend has continued downward, as news outlets of all stripes continue to suffer drops in circulation, readership and ratings declines, leading some expert observers to worry about the future of democracy itself.

In the most recent poll, the percentage of Americans reporting they follow news about national politics “very closely” has dropped to 32 percent, what Gallup calls a more normal level of interest in nonelection years.

“Still,” Gallup says, “the public continues to pay greater attention to politics than it did in the 1990s and early 2000s, when less than 30 percent were tuned in.”

Voter Turnout

That level of public interest in public affairs may surprise those who remain highly interested and engaged even on social media. But it is no surprise to those of us in the business who have long known that keeping a majority of the public engaged about politics is not easy. Just notice voting rates in the U.S.

The lowest voter turnout ever recorded came in 1996, when less than half of Americans, 49 percent, turned out to vote in the election between Bill Clinton and Bob Dole in that election year.

In 2020, after four years of Trump on Twitter and the harrowing experience of the coronavirus global pandemic, voter turnout reached a peak of 62 percent, a level not seen since the election of 1960 when Richard Nixon and John Kennedy faced off on the radio and television at the hight of the Cold War and the science and nuclear weapons race with Russia.

The latest results from Gallup’s annual Governance survey are from polls conducted between Sept. 1-23, prior to Congress passing a short-term federal government funding measure to avoid a government shutdown. The news attention question has been asked on the Governance survey most years since 2001 and had been asked on other Gallup surveys before that, starting in 1995.

In addition to the 32 percent who currently say they are paying very close attention, 41 percent say they follow national political news “somewhat closely,” while 19 percent say “not too closely” and 8 percent say they don’t follow it “at all.”

The four highest readings in Gallup’s trend were all measured in presidential election years, including 43 percent in 2008 when Barack Obama was seen as something of a political rock star and the 42 percent in 2020 when Trump was seen by many as an existential threat to democracy.

Demographic Differences

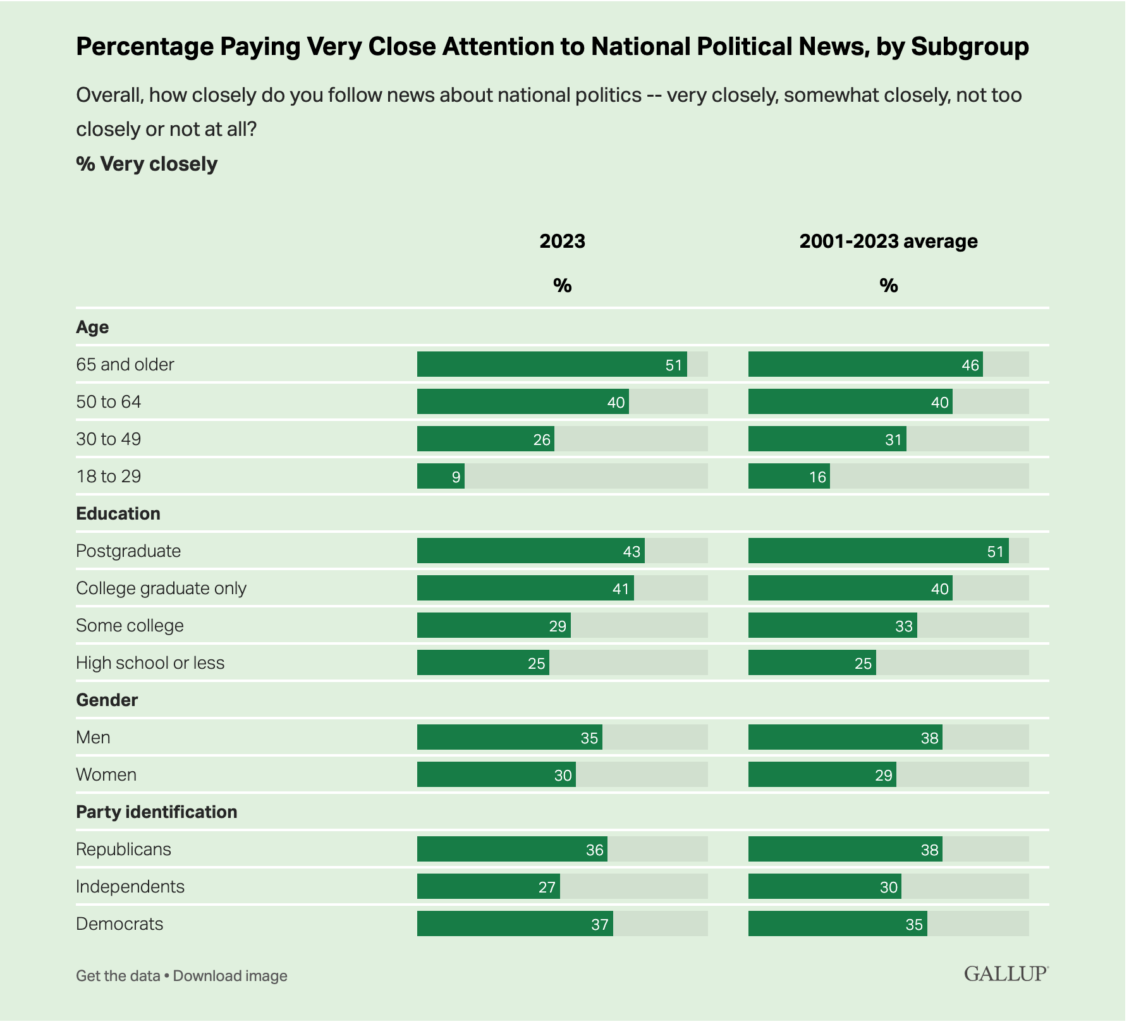

There are wide differences in the amount of attention paid to national political news by age and educational levels. In the most recent survey, 51 percent of adults aged 65 and older say they follow political news very closely, followed by 40 percent of those between the ages of 50 and 64. Far fewer 30- to 49-year-olds are following politics very closely, 26 percent, while only 9 percent of those between the ages of 18- to 29 say they are paying attention.

More than four in 10 college graduates (including those with and without a postgraduate education) follow political news very closely, while fewer than three in 10 adults without a college degree say they do. Of course Trump got many of those without a college education to pay attention and vote, some for the first time.

There are modest gender differences in attention to politics, with more men (35%) than women (30%) following politics very closely. Republicans and Democrats pay similar levels of attention, but independents pay less attention than either of the two major party groups. Postgraduates typically pay the closest attention to politics, with an average of 51 percent of those with graduate degrees paying attention, at least since 2001.

The News Business

The Columbia Journalism Review in New York is keeping up with the problems plaguing the news business, and recently published a special issue exploring the various business models being developed to deal with it, leading off with the problems at The Washington Post.

Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, who owns the Post now, recently showed more of an interest in the publication when it was announced that the company would lose $100 million this year and announced layoffs and buyouts of a significant percentage of the staff.

We reported on this back in July.

The State of the News Media and What That Means for Democracy

According to the CJR, Bezos sat in on a news meeting, but “didn’t say much.”

“Staffers crowded in, feeling panicky. Weeks earlier, Fred Ryan, the publisher, had announced there would be layoffs, then took no questions. Now an employee approached Bezos to ask about the cuts.

“Believe me,” he replied. “I’m committed.”

Within days, the Post laid off 20 people and said the paper would leave 30 vacancies unfilled.

“That marked the beginning of what has become media’s worst year on record for job losses,” CJR reports.

In August, even Ryan left the Post. Bezos reportedly entered “a period of renewed engagement” with the paper. In October, the Post told staff that it would eliminate 240 more jobs through voluntary buyouts.

“Across the industry, thousands of journalists, of every form, have been forced out of work,” the CJR reports “Blame has been placed on a tumultuous economy, plummeting ad revenue, a collapse in social media traffic.”

In conversations with people in the business, they say, “there is often a sense of despair…”

The management of these news organizations have made many decisions that did not help the situation, and according to CJR, “those decisions have impact.”

“Over the course of this difficult year, many in media have grabbed hold of that idea as a means by which to pull themselves out of the muck. They are turning to one another, and directly to readers. They’re trying new things,” they say. “Not all of their experiments are viable, or even good. They’re still figuring it out—aiming, one way or another, to exert control over what comes next.”

I hate to say I told them so, but I saw this coming 25 years ago, when I started The Southerner magazine online and spoke about the future of newspapers in print at Birmingham Southern’s annual writers conference at the turn of the century and the new millennium in 2000. There are many in this industry who must still resent what turned out to be an accurate prediction about the future of newspapers in print.

Management at what’s left of the online newspapers are still ignoring those of us who set out to innovate and create a better press online that long ago. And these arrogant managers are still failing, for the most part, to understand that the public doesn’t care about their profits. It’s not about the money and capitalism. What people care about is how we play our historical and constitutional role in protecting democracy, and how we use the influence of the press to preserve life on planet Earth.

Everything else is filler and clickbait.

Part of the problem is that when mass circulation daily newspapers made the transition from print to digital, they retained many of the same sections that made them money in the print era in the 20th century. But both the New York Times and Washington Post have scrapped their weekly magazines in recent years, and the Times recently fired its entire sports news staff and now relies on coverage of sports from The Athletic, an online magazine it purchased a few years ago. Now they charge extra to read it in addition to the paywall for the rest of what’s left of the online newspaper.

Then there are the indomitable Food sections, gossip and advice columnists, and all the coverage of stuff that has nothing to do with public affairs, which gave the press in the U.S. special rights under the First Amendment to the Constitution in the first place. When I created the New American Journal in 2014 after experimenting with web publishing for more than a decade, I vowed to jettison those extraneous sections to concentrate on the categories that matter. The one exception is the Travel section, which is clearly something of heightened interest these days after people suffered from the Covid lockdowns and stay at home orders during the pandemic.

But of course most of that traffic has now moved to social media, especially Meta’s Facebook, as people tell their own stories and post their own pictures for their friends to see. They seem to be ignoring similar pictures and stories published by the press and not sharing news links on the platform, which seems to be the goal of the social media publishers like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk, as well as Donald Trump.

Why do we need news reporters, editors and photographers when people can become publishers themselves, and all the advertising money these days just goes into the pockets of tech billionaires?

Sorry, but I don’t believe that selfies and phone pictures and funny memes and videos are going to save democracy or the planet. Maybe people don’t understand this, or maybe they just don’t care?

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal. We just tell it like it is, no sensational clickbait or pretentious BS.

Well written as usual, Glynn.