The Big Picture –

By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. — It was as hot as I believed hot could get when I landed at the Louis Armstrong International Airport in New Orleans in the midst of the first August of the new millennium. Even in a summer Searsucker Suit the hot air hit you in the face as a shock. Global warming was already in full swing, confirmed by the science.

We celebrated the New Year of 2000 with a blast and not a care about the Millennium Bug at Sassy Ann’s blues bar in Knoxville. Yet here I was off on another adventure like Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, or Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn drifting down the Mighty Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico.

Teaching three courses full time and advising 50 students at full pay was interesting and fun for the most part at Loyola, except for the faculty meetings, which were like a political war zone. One of the first things I did was setup a new Mac computer lab, where we taught the writing courses. Little red Apple’s dotted the room, where students could learn to write news on computers, not typewriters.

The Dallas Morning News

But a big chance to free-lance came along right away after I moved into my office at Loyola. They bought me a grey spaceship Mac G4 computer. In October, I got an email from the editor of the Texas and Southwest section of The Dallas Morning News, a top 10 circulation newspaper in the U.S., looking for a new stringer in Louisiana. I was new in town, and didn’t know enough about my students or anyone else to recommend. I knew I could do it, so I offered up my resume and clips.

Within days I was filing on a regular basis, breaking news and features. Over the next three years, I would produce the Sunday centerpiece news feature on multiple occasions, and break news too. It was lucrative enough to augment my university salary and pay for an upscale duplex in a desirable Uptown neighborhood on Plum Street, near the street car line on Carrolton Avenue and several world class bars and restaurants. My favorites? The Maple Leaf Bar and Jacques Imo’s Cafe on Oak Street.

Life was good. I mean really good, at least for me. There was golf at Audubon Park a couple of times a week, and sometimes a little tennis with my good friend Rick Bragg, who moved to New Orleans from Miami a few months after I did — after the Supreme Court finally ill-decided the case of Bush v. Gore. In those days we liked to quote Boudreaux from time to time, a working class jokester of a man like us, only Cajun. He liked to say, “Wooiee. How do ya know you’re winnin’, that ’tis in the game of life? By how much time you spend on the golf course.”

It finally felt like I found the perfect apartment in a great city, with the budget to decorate a writer’s residence to completion. It was a duplex with 14-foot high ceilings, hard wood floors, three fireplace mantles, a big window looking out over a garden where I setup my desk. There was also a back porch with wild parrots nesting in the yard, and a front balcony looking at the Plum Street Snowball stand, ostensibly the second best in the city. The place in Knoxville was great too in that big old mansion up on the hill looking out over the campus. Oh, the parties, especially on football Saturdays.

This was better. Except for the weather. Sometimes you could not get your hair dry after a shower in the Big Easy swamp.

And eat your hearts out students and teachers of today. The 90-year-old Jewish lawyer who was my wonderful landlord only charged $550 a month, and never went up on the rent, if he liked you. He liked me, and read some of my writing in Gambit Weekly, the alternative weekly in town.

While teaching full time and free-lancing, I began working on a dissertation in earnest, and had about a year and a half to get it approved and move forward toward tenure. Perhaps that should have been my priority. I did the research and wrote the dissertation. But I never liked the long drawn out process of academic publishing, not the way I liked publishing in newspapers, magazines or on the web. There was something rewarding about the instant gratification.

I finished the dissertation early in the morning hours of September 11, 2001. Maybe you recognize the date as 9/11. I went to bed around 2 a.m. Of course when I woke up in the morning and turned on CNN, I knew I was in trouble.

That had to be about the worst timing of my life. Usually my timing has been good, if not great. Whoops.

It’s all in the book.

Jump On The Bus: Make Democracy Work Again

It didn’t matter. As I explain in the book, teaching was a backup plan for me anyway. As they say, “Those who can do. They who can’t teach.” I was doing it in style and didn’t feel like I needed a Ph.D. to be a journalist.

In fact, in an exit interview, the chair of the Communications Department at Loyola who headed the committee that recommended hiring me apologized and said he voted for me. I only lost out on a contract renewal by one vote. He offered to write a letter of recommendation if I wanted to keep chasing college teaching jobs all over the country.

“That’s OK,” I said. “I think I’ll just practice a little journalism for awhile.”

He taught film studies, not journalism.

The Christian Science Monitor

By the spring of 2022, when the gig was up and I knew I was probably not going to be teaching anymore, a British editor with The Christian Science Monitor found my stuff online and called me up, wanting me to become a Special Correspondent for the well respected paper out of Boston. I said sure, and started producing breaking news stories and features for them as well.

You can read some of the clips from here on this early web page: A Portfolio Online.

I was having the run of my life as a super duper free-lancer in New Orleans, and then the ultimate opportunity knocked. In the summer of 2022, I had the lede story in the Dallas Morning News on the West Nile virus when it was declared an epidemic. I was ready for this one. Health science is not my favorite specialty, but I knew it was coming.

The New York Times

The day the CDC declared it a national epidemic, I had lunch with Bragg at Dunbar’s soul food restaurant on Freret Street, just down the street from the Loyola campus. He ordered the fried chicken, as usual, and I may have too. It was probably the best thing on the menu.

Over lunch, Bragg tells me National Editor Nick Fox had called that morning, asking for help on the West Nile story.

“What did you tell him?” I asked, sitting back picking my teeth with a toothpick.

“I told him hell no,” he said, since he was still on sick leave. He had been to UAB Hospital in Birmingham and diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes. He was not feeling well.

I said, “Well, when you get back from lunch, call him and tell him I can help. I just did the story for The Dallas Morning News.”

On the West Nile front line: Louisiana town acts to squash mosquitoes carrying virus

For some reason, the editors at the Times liked the Dallas paper. They didn’t use their own local papers as a farm system the way they should have, but they hired people who had worked for the Morning News.

By the end of that afternoon, after phone calls and emails were exchanged, and a resume and clips forwarded, I found myself working for The New York Times. It was only a dream I once had, one I never thought would come true. Not considering where I was from, and what all I had been through. But there it was, my byline on the front page of the Sunday New York Times.

By RICK BRAGG with GLYNN WILSON

Burning of Chemical Arms Puts Fear in Wind.

To make the clip even better, I got the Times photo department to hire my close friend Spider Martin to work as the photographer on the story.

After this story came out, I happened to run into the film studies professor one day in Audubon Park. He was walking through the park. I rode by on my Cannondale and gave him a little smile and a nod. The look on his face was priceless. He was stunned. He had not considered that I was about to be on the front page above the fold in the Sunday New York Times.

Funny, but I literally can’t remember his name. I bet he remembers mine, if he’s still alive. Sorry if I felt a little smug at that point. Over the next few years, I worked with probably seven different correspondents on big national stories, breaking news and features, politics and the environment.

Dow Water

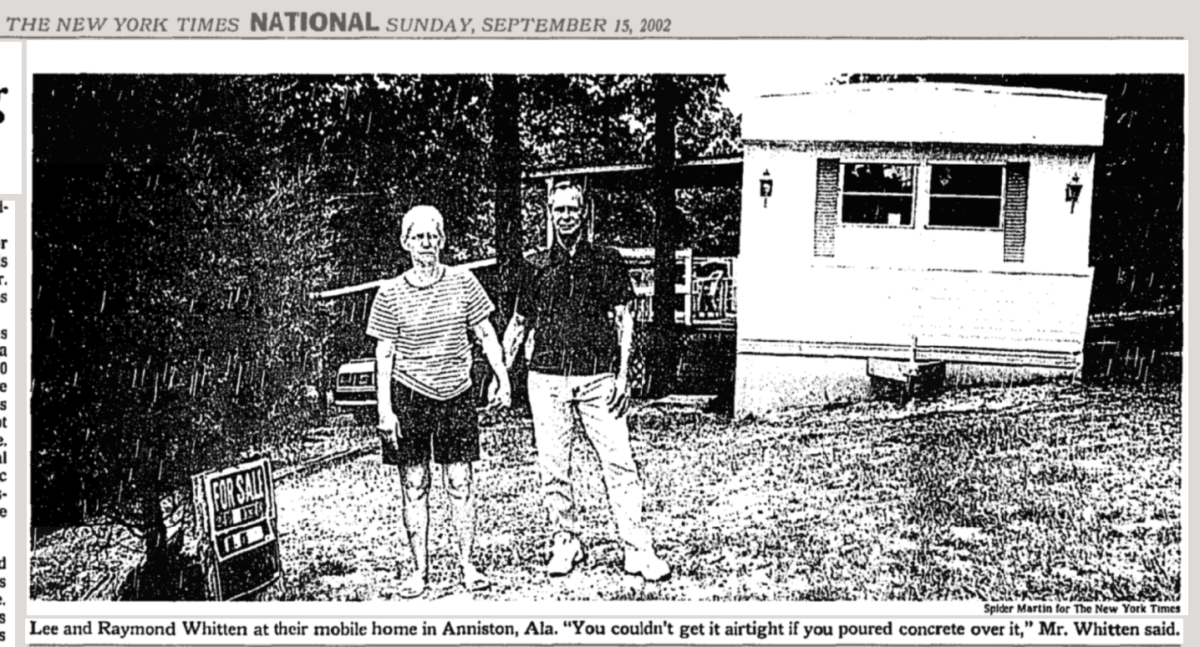

In one of the most interesting and important environmental stories we did, I noticed a little story on the wires about a community of people living in a trailer park in Plaquemine, Louisiana, who were becoming sick and blaming it on well water they thought must be contaminated by chemicals from a nearby Dow Chemical plant. Of course the company denied it. But a lawsuit was filed, blaming the problem on vinyl chloride, which was manufactured at the plant and found in the water.

To try to avoid legal liability, the company commissioned a study that erroneously claimed the water in the underground aquifer flowed primarily to the west, not toward the trailer park, which was southwest of the plant.

I pitched it to the National Desk, and Bragg agreed to work with me on the story.

In researching the case, I contacted Wilma Subra, a chemist and consultant to the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, who was following the case and keeping up with all the documents. (She would later go on to be awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship grant.)

She provided me with a copy of tests run by the Environmental Protection Agency, which showed that the aquifer, 190 feet below the surface, actually flowed in a south to southwest direction from the plant, which would carry it directly under the trailer park. Nailed it.

The National Desk at that time was not giving many bylines to free-lancers. I was told that we would only get a byline “if we could not have gotten the reporting any other way.” I did about a month’s worth of research for the Anniston incinerator story as a specialist in covering the environment, so I got a byline on that story. The Science Desk had a policy of only giving bylines to free-lancers who had formerly worked for the Times as staff correspondents.

I did not complain. I was enjoying the work, and the money coming in from it.

But this story was my idea, and I did the key research that nailed the story. This clip was used as an exhibit in court, helping the poor people get a settlement from Dow paying to move them into better, safer housing.

It’s a beautiful story, written by Rick Bragg. But I was right there looking over his shoulder while it was being written, feeding him the facts.

Toxic Water Numbers Days of a Trailer Park

After the story came out in the paper, Ms. Subra wrote a letter to the editor saying it was one of the most beautiful environmental stories she had ever seen in a newspaper. When I emailed it to Bragg, he replied, I kid you not, saying “That’s why we do this.” It was a good feeling knowing we could help people simply by telling a story in the newspaper in a certain way, framing the issues correctly and nailing down the facts.

That’s the power of the press in a democracy. Make no mistake about it.

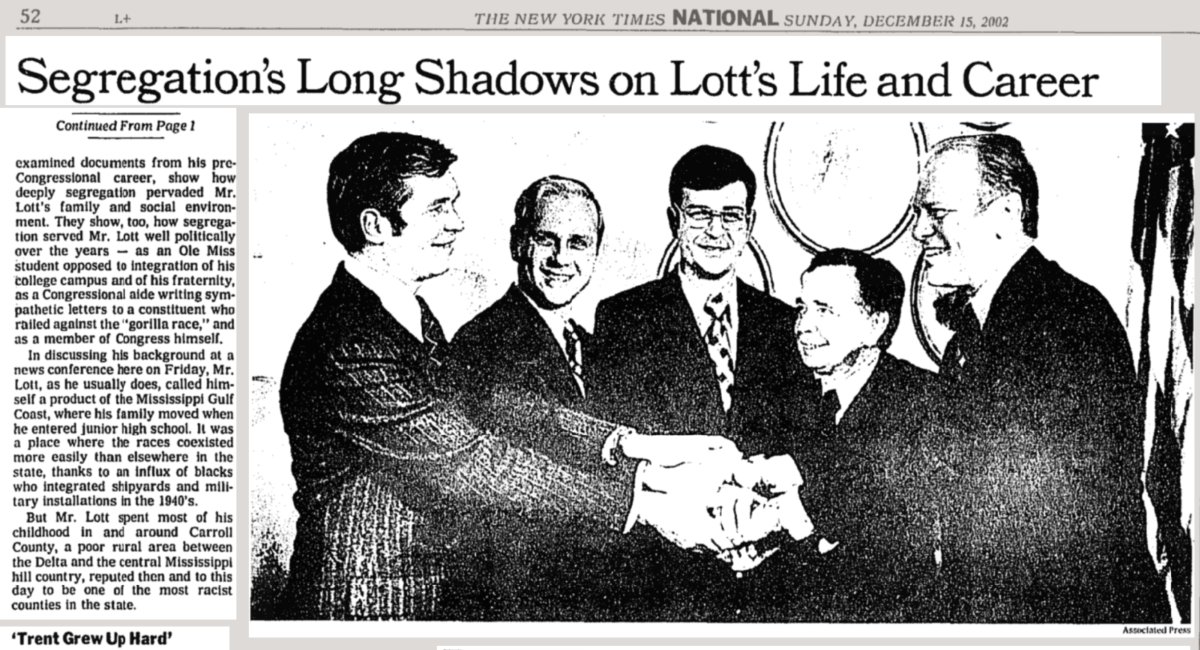

Trent Lott

In one of the most interesting and important political stories I did a significant amount of work on involved then U.S. Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott. In December, 2002, Lott attended Strom Thurmond’s 100th birthday party in Washington and made comments he would come to regret.

“I want to say this about my state. When Strom Thurmond ran for president, we voted for him. We’re proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn’t have had all these problems over all these years either.”

The story did not generate a firestorm of critical coverage right away, although in the early days of the internet and blogging, there were a few people screaming about it. I saw a major story opportunity right away. Digging around for an angle, I got a tip from a journalism professor at the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg, someone I knew in person. We taught a class together at the University of Alabama when he was in the Ph.D. program and I was working on the Masters.

While Lott was going on television denying that he had ever been a racist, Dr. David Davies told me the date had arrived when Mississippi Congressman William Colmer’s papers were to be opened to the public for the first time at the special collections library. Lott worked as Colmer’s administrative assistant in the late 1960s and became his heir apparent in Congress in the early 197Os.

Nick Fox, who is now on the editorial board of the Times, called me back and said, “How soon can you be in Hattiesburg?”

I said, “Oh, about an hour and a half.”

Jump on the bus.

No one else had seen the papers, not even a research librarian. I was the first.

Here is a story I published in October, 2011, telling the whole story. The Upshot is The New York Times, based on my research, proved that Lott had in fact been against integration and busing, and wrote racist letters to constituents he signed.

How The Trent Lott-Strom Thurmond Story Grew Legs and Crushed a Political Career

In one of the most gratifying moments in my journalism career, I was in Trent Lott’s driveway in Pascagoula, Mississippi with the press corps on that Sunday before Lott stepped down as Majority Leader. I noticed the Sunday New York Times being dropped on his front porch by the paper boy. I waited and watched, and saw Mr. Lott come out the front door of his house across the street from the beach and pick up the paper. He wore a bathrobe and gave a little wave to the press. Some shouted questions at him, which he refused to answer. He picked the paper up and took it back inside. I knew he was going to have a heart attack when he saw the story above the fold in the Times.

Oh, to be a fly on the wall.

In Lott’s Life, Long Shadows Of Segregation

It’s a brilliant story, written mostly by David Halfbinger with some help from Jeffrey Gettleman. But it was my research that drove Lott from power. I should have been given byline credit.

But that was not the policy of the National Desk.

Halbfinger and the copy editor Lawrence Downs later told me they almost led the story with the letters I obtained. But they decided not to, because they would have had to give me byline credit if they had.

Bummer.

I didn’t really understand or agree with the policy, but at the time, I did not complain. I cashed the $1,000 check I got for working on the story, and went on to work on the next story. To me it really was a lot of fun. I didn’t mind working as part of a team. There was no ego in it for me.

Once the Times released me and said we were done on that story, I had another idea for a story for The Christian Science Monitor. That Sunday night, before heading back to New Orleans, I attended Sunday night services at the First Baptist Church of Pascagoula, Trent Lott’s church.

In addition to the check I got from the Times, I got another $300 for this byline story.

In Mississippi Gulf, divided views on Lott

Now that’s the way to make a living as a free-lance writer. I was great in the field on deadline. Send me out on a story and I always come back with good stuff. I still am that good in the field on deadline. Only nobody wants to pay for free-lance journalism anymore, so I just publish it myself here.

On a couple of other high notes, also in August of 2002, I noticed that the Southern Governors Association was about to hold its annual meeting at the Ritz Carlton Hotel on Canal Street, on the edge of the French Quarter. I obtained a copy of the agenda, and starting pitching stories, trying to get some editor to agree to pay me to attend.

The Dallas Morning News, the Christian Science Monitor and The New York Times did not seem interested in the stories, so I contacted the wire service I had worked for on and off for nine years, United Press International (UPI). I told the editor in the Washington bureau, who I had known and worked for when he was in Miami, Tobin Beck, that former New York Mayor Rudi Giuliani was delivering the keynote address over lunch. UPI agreed to pay me $150 to go and see what I could extract in the way of a story.

I got there a little early, but avoided the big press gaggle in the back of the room. I entered through a side door and sat on the front row. I would later find out that Giuliani had requested that all media only be allowed to cover the first 10 minutes of his address so he could openly discuss “national security issues” with the governors. They all agreed and exited to the rear after 10 minutes.

Giuliani had become famous as “America’s mayor” in the aftermath of the attack on the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. (Of course he has certainly turned it all into an embarrassment now, eh? You think he has unfulfilled hopes, or shattered dreams?)

I figured it would not matter much what he said. Whatever it was, it would be news. I did not get the memo about leaving after the first 10 minutes, so I ended up being the only reporter in the room to hear everything he had to say — and I took notes.

At a press event after the lunch, reporters were asking him all kinds of questions, which he mostly dodged. I realized I had the only notes that mattered. I began looking through my notes during the press conference, trying to figure out something to ask. I asked one question, but do not remember what it was, or the answer. The notes contained the story, if you knew the context. I quickly opened my laptop and starting typing the exclusive breaking news story.

Giuliani reveals thoughts on WTC site

Some days if you put yourself in the right position, you get lucky. Man I was riding high, having the most fun of my life as a journalist.

But of course it was not to last, and I figured all along that it wouldn’t. That’s the story of my life. I jump on the bus and do the job, and somebody else comes along to screw things up.

In May of 2003, Howard Kurtz broke an explosive story on CNN’s “Reliable Sources” Sunday show on the media. A Black kid named Jayson Blair with only a partial college education at the University of Maryland had been filing some very well written stories as a Times correspondent. The problem was, he had not been traveling to the places where the stories occurred, especially El Paso, Texas.

Instead, he had been lifting quotes, description and other information from local newspapers and the Times photo archives and passing it off as his own work in the Times. We call that plagiarism. Now if Blair had the full education and the experience to know that he could have used free-lance stringers on the ground in places, and if he had only cited the work he was lifting, he may have been able to ride out the scandal.

In my view he was promoted too fast by Editor Howell Raines and the Managing Editor, a very qualified Black man. I can’t recall his name.

The scandal upset the balance of power at the Times, and caused a huge uproar.

Everybody who was anybody started investigating and covering the story, including a team at the Times itself. I followed every story with agony, figuring my run with the Times may be over soon because of this scandal. That didn’t turn out to be true, exactly, although the amount of work dropped after Bragg quit and editor Howell Raines, also from Alabama, was forced to step down, no doubt with a golden parachute contract.

(The full story on what actually happened has never been told. I’m saving some of those details for another day).

Meanwhile, by the fall of 2023, with my free-lance business still going but dropping some, I had one of those times when I felt like it was time to reevaluate my priorities and decide what to do next. I was growing a little tired of New Orleans. It was an interesting city with a lot of cool stories to cover. But I felt like I had covered most of them. Maybe it was time to move on.

I was thinking about finally making the move to Washington, D.C., something I probably should have done early in my career. But the right opportunity never seemed to come along, until popular Mayor Ray Nagin came along. People may recall Nagin as a crook, who was later found guilty of political corruption and sentenced to prison. But he was still popular at this time.

I liked him. I attended his inauguration party in early December after he had been elected in November at the Astor Crown Plaza on the corner of Bourbon and Canal Streets. It was one of those political parties of a bygone era when the press was treated to free food and a full bar, and this was New Orleans food and drinks. I wore shiny grey slacks, black Bostonian shoes, a white button down shirt and a black camel hair dinner jacket. That was my uniform as a “Timesman.”

This is the story I produced from that party.

New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin’s ‘Honeymoon’ May be Over

As I left the party and rode the elevator down to the lobby, I noticed a young Ivy League tweedy looking fellow with patches on the elbows of his sports coat, about to get on the elevator. He looked a bit lost. For some reason I decided to introduce myself, and found out it was a new editor at a new magazine in New York called Details. He had just arrived in town looking for new talent and stories, he told me. After we talked for a few minutes in the lobby, he offered to buy me lunch the next day in the French Quarter.

I met him and decided to pitch a story I had wanted to do since the election of 2000, when The Boston Globe broke a story claiming George W. Bush had gone AWOL from the Texas Air National Guard in 1972. I found out Bush had ended up working on a political campaign that year in Montgomery, Alabama, and I wanted to go there and investigate to see if I could unearth the full story.

If he bought the story, the plan was to pack my stuff in a U-haul truck, move it all back to Birmingham, and spend a few weeks in Montgomery before making the move to Washington. It seemed like a good plan at the time. He took the story back to his editors in New York, and I signed a big magazine contract. If the story had worked out like we planned, I would write about 7,500 words for $1.25 a word, or about $9,000. That would easily pay my moving expenses to Washington and then some.

I wrote my last story for The Dallas Morning News in December, a big Sunday story about what would happen if “the big one” ever made a direct hit on New Orleans, a few months before Hurricane Katrina came up the Mississippi River and overtopped the levies, putting much of the city under water.

Global Warming Makes Saving Louisiana’s Wetlands Hard

The editor wrote a letter recommending me for a mid-career Neiman Fellowship at Harvard, but my good friend Don Schanche from Georgia was picked that year.

It was Christmas time, so I did a little shopping in the French Quarter. Then moved back briefly to Birmingham, and spent time in Montgomery, doing reporting on the story.

I worked on the Bush AWOL story, wrote 7,500 words, and turned it in on Jan. 2, 2004. Unfortunately, the kid editor didn’t know what he was looking at. He said he did not understand the story, and asked me to cut it in half and make it simpler. I did it, but he still didn’t get it. He said he was on his way out of town to the Sundance Film Fest and would just have to pay the kill fee in the contract, which was $2,250. I said fine, that covered the expenses of doing the story, and started trying to sell it to a magazine with an editor who knew something about Southern politics.

The old editor at The Atlantic took a look at it, but passed. The next week, Michael Moore was on MSNBC and called Bush “a deserter.” I knew every major newspaper in the country would have a Bush AWOL story by the weekend. I pitched it to the Times, but they had sent a woman education reporter to Montgomery who had the flu. I talked to her on the phone and offered to help her on the story, but she declined. My inside contacts at the Times were gone, Howell Raines and Rick Bragg. The Times‘ story was the worst of all the ones published. They could have had my reporting, but declined.

So I said “fuck it,” and refused to get beat on the story. I published this on The Southerner website.

George W. Bush’s Lost Year in 1972 Alabama

It was found on the web with search engines, picked up and quoted in The Village Voice, Time magazine stole from it, and Kitty Kelly would later write a book about the Bush family and use it verbatim. It literally became the lynchpin of her case against George W. She did cite it in the end notes, but did not properly credit me. So I found a lawyer, who sued in federal court.

The New York Times interviewed me and wrote about it.

A Writer Is Suing the Author of a Hit Book on the Bushes

Unfortunately, I ended up dropping the case, because the lawyer didn’t do his research before filing the lawsuit. In the 11th federal circuit, there was a precedent on the books that favored big New York publishing houses, in this case Random House. To bring a successful case of copyright infringement, I would have had to print the story out off the web, mail it to the Library of Congress in Washington, and pay a $30 filing fee — in advance of the book’s publication.

I did print it out, mailed it and paid the fee before we filed the lawsuit, but not before the book was published. It was just not practical to print out every story published on the web and mail them to Washington. That would have been absurd. The story carried the copyright notice, but the legal framework for that had not been developed. As far as I know, it’s still not developed.

Oh, well. Just another setback and disappointment. Clearly the publishing industry is not always ethical. But my story stands the test of time. I may not have fit the clickbait bill people were looking for, proof that Bush went AWOL. CBS’s Dan Rather blew his career by screwing up that story and using documents that could have been faked. If he had seen my story, he could have realized the accurate framing of the story.

Whether Bush was technically AWOL or not — and the truth is he wasn’t — it was still a major story, a story of a privileged son getting away with crap most of us would have been locked up for.

But that did not stop me from making the move to D.C.

I had saved up a good bit of money from free-lancing, I had the clips, so I rented a van and moved into an apartment in Alexandria, Virginia, just across the Potomac River from downtown D.C.

___

More Part 5: On Unfulfilled Hopes, Shattered Dreams and Covering News in Washington, D.C.

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal. We just tell it like it is, no sensational clickbait or pretentious BS.