O wondrous youth

Through this grand ruth

Runs my boy’s life, its thread

The General’s fame, the battle’s name

The rolls of maimed and dead

I bear with my thrilled soul astir

And lonely thoughts and fears

And am but history’s courier

To bind the conquering years

A battle’s ray, through ages gray

To light to deeds sublime

And flash the lustre of my day

Down all the aisles of time.

– War Correspondent Ballad, 1865

Secret Vistas –

By Glynn Wilson –

CRAMPTON’S GAP, Md. — Summer in America is a time of travel and holidays. These days that might mean dodging wildfires, running from hurricanes or flash floods, and Covid.

But from Memorial Day in May to Labor Day in September, Americans find ways to get out of the house, their hometown and travel, even with the price of gas hitting record highs.

There’s Juneteenth and Independence Day, the quintessential American holiday on the Fourth of July.

Some might argue that we have too many federal holidays. Others could say we have too few.

Let me offer up two new ones for debate.

Obviously I’m not the first one to point out that Election Day in the United States should be a federal holiday. What better way to make it easier for more people to vote than to give them the day off?

In the days of George Wallace in my native state of Alabama, he had the legislature pass a bill shutting down the state liquor stores on Election Day, so at least it would be hard to get drunk and not vote — for him of course.

Oh, wait. We have one party today that’s future relies on suppressing the vote. That’s why this great idea can’t get a hearing, a debate or a vote in the U.S. Senate. The House has passed a couple of bills in the past with this provision included.

But some so-called moderate Democrat in West Virginia is holding it up, like everything else, along with Senate Majority Leader Mitch “Turtle Neck” McConnell of Kentucky, home to a racist theme song, My Old Kentucky Home.

Maybe one of these days, if we survive long enough, we might see that holiday added to the annual schedule.

To set up and provide the background for the other national holiday we need to ensure our future, let me travel south to South Mountain, where one brave war correspondent took it upon himself to honor and celebrate the significant role American journalists played in fostering democracy in the United States. To the War Correspondents Memorial Arch.

We made the trip down Monday the day before the Summer Solstice, after thinking about it and talking about it for years.

The idea here is that the soldiers could not have won all our wars by themselves. So I often ask myself why we have three national holidays celebrating the military and none celebrating freedom of the press and the courage of writers and photographers who covered all our wars, including those whose writing inspired the Revolutionary War against King George III and Great Britain?

There would likely not be a United States of America without the words of Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin’s newspapers. George Washington’s beleaguered army could not have defeated the Red Coats all by themselves. We needed public opinion on the side of freedom, democracy and revolution, and that sympathetic public opinion was provided in a big way by the press.

That’s why it is inshrined in the First Amendment, along with freedom of speech and the rest.

So that’s why I say we need a new national holiday honoring FREEDOM of the PRESS.

Not just journalists killed while covering war, but something to show “the people” that members of the press are not “the enemy of the people” that a certain discredited politician liked to call us. We are as critical to the future of democracy as the U.S. military.

It’s really a crying shame that no newspaper editor or publisher had this idea and pushed it through back in the 20th century, when newspapers had the power.

At least we have one or two monuments to journalists killed in war, although I suspect very few people have ever heard of them or visited.

The National War Correspondents Memorial, once entrusted to the National Park Service but now part of Gathland State Park, is a memorial dedicated to journalists who died in war. It is located in Maryland, at Crampton’s Gap on South Mountain, part of the Cotactin Mountains in the Appalachians.

George Alfred Townsend, nicknamed “Gath,” who covered the Civil War for newspapers, bought the land that is now a state park and built the arch at his own expense in 1896, dedicated on October 16 of that year.

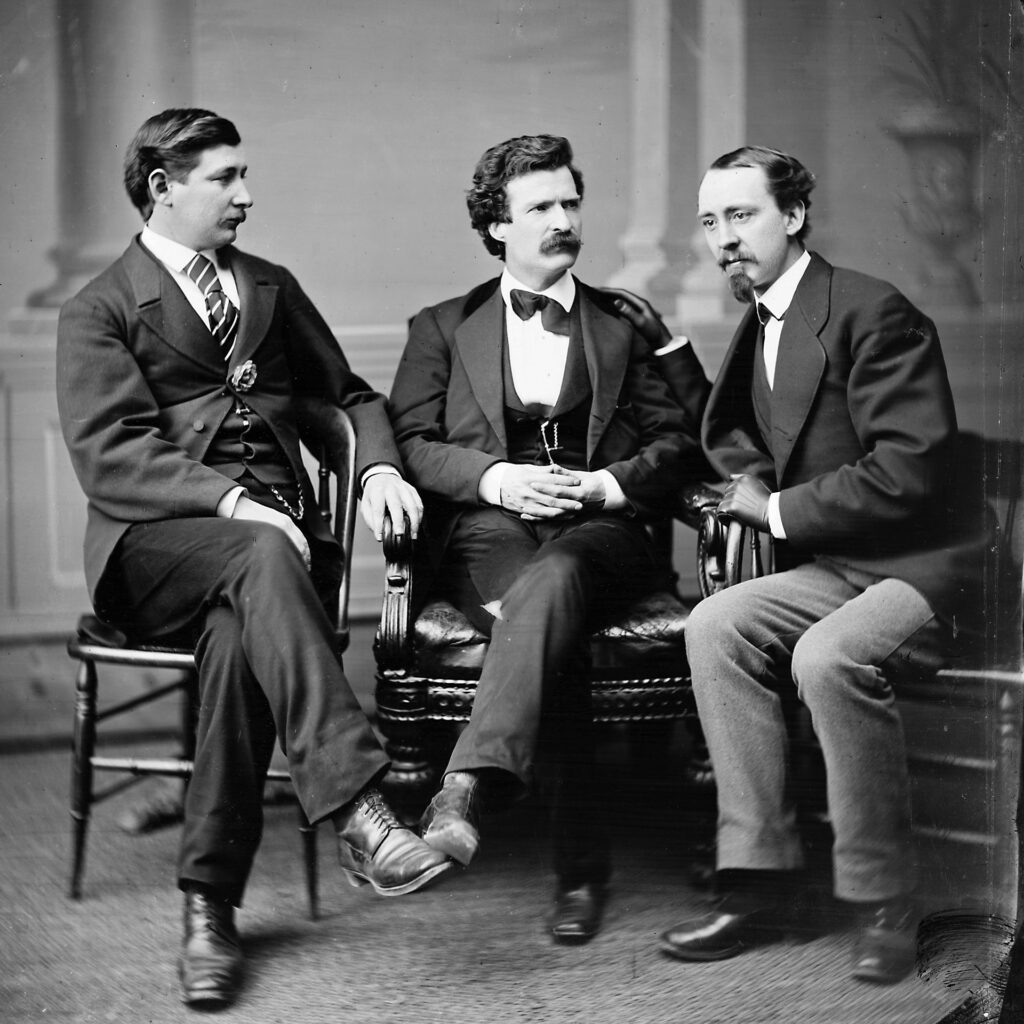

This photograph of Townsend (left) with Mark Twain (middle) and David Gray, was apparently taken by either Mathew Brady or Levin Handy. It is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cwpbh.04761. This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required under Creative Commons Licensing.

“Published photographs in this collection were created before 1923 and are therefore in the public domain. Unpublished photographs in this collection are also in the public domain as Mathew Brady died in 1896 and Levin C. Handy died in 1932.”

It is claimed that the arch is the only monument in the world dedicated to journalists killed in combat, although there is a tree in Arlington National Cemetery dedicated as a war correspondents’ memorial also in 1896, and other countries have since added their own memorials.

Me and my friend Brooks Boliek wanted to know more about this monument and Townsend, so we made the trip down this week.

George Alfred Townsend (January 30, 1841 – April 15, 1914) was an American journalist and novelist.

He worked as a war correspondent during the Civil War. Townsend wrote under the pen name “Gath”, which was derived by adding an “H” to his initials. He claimed it was inspired by the biblical passage in II Samuel 1:20, “Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Askalon.”

Townsend was born in Georgetown, Delaware, on January 30, 1841.

Apparently his first newspaper writing job was with The Philadelphia Inquirer, but in 1861 about the time of the South’s succession from the Union and war he moved to The New York Herald and wrote for editor and publisher James Gordon Bennett. In his early 20s, it is said that Townsend was the youngest correspondent covering the war.

Among the biggest stories he covered was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the escape and capture of John Wilkes Booth. His daily reports filed between April 17 – May 17, 1864, were later published in 1865 as a book, The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. It was reprinted in 1977, and published in audio version in 2009.

By 1865, Townsend was the Washington correspondent for The New York World, the paper founded in 1860 by Joseph Pulitzer.

Immediately following the war, Townsend married Elizabeth Evans Rhodes of Philadelphia. By 1868, he had become one of the most quotable Washington correspondents, working for The Chicago Tribune, and after 1874, for The New York Graphic.

His letters, published several times a week, were several columns long, and included lively word-portraits of politicians and opinion.

Near the end of his career, he established and edited, with an Ohio journalist and politician Donn Piatt, the Capital in Washington, D.C., which started up in 1871. But shortly thereafter he parted company with Piatt for unknown reasons, and apparently retired to Crompton’s Gap near Burkittsville, Maryland and the present day Antietam Battlefield Park, where they still call it “the Bloodiest Day in American History.”

There 23,000 soldiers were killed, wounded or missing after 12 hours of savage combat on September 17, 1862. The Battle of Antietam ended the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia’s first invasion into the North when the Union army chased them off and down the hill where the monument stands today. It also prompted Lincoln to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, in part to recruit more African American soldiers to help prosecute the war.

In 1884 Townsend began building a baronial estate in the Catoctin Mountains called “Gapland” on the site of the Battle of Crampton’s Gap. The estate is composed of several buildings, including Gapland Hall, Gapland Lodge, the Den and Library Building, and an (unused) mausoleum, notable for its inscription of “Good Night Gath”.

His novels included The Entailed Hat (1884), which fictionalized a true story of a woman named Patty Cannon who kidnapped free blacks and sold them into slavery. Townsend’s other works include the short story collection Tales of the Chesapeake (1880) and the novel Katy of Catoctin (1887).

Townsend described the monument this way:

In appearance the monument is quite odd. It is fifty feet high and forty feet broad. Above a Moorish arch sixteen feet high built of Hummelstown purple stone are super-imposed three Roman arches. These are flanked on one side with a square crenellated tower, producing a bizarre and picturesque effect. Niches in different places shelter the carving of two horses’ heads, and symbolic terra cotta statuettes of Mercury, Electricity and Poetry.

Tables under the horses’ heads bear the suggestive words “Speed” and “Heed”; the heads are over the Roman arches. The three Roman arches are made of limestone from Creek Battlefield, Virginia, and each is nine feet high and six feet wide. These arches represent Description, Depiction and Photography. The aforementioned tower contains a statue of the Greek god Hermes (Roman god Mercury), the messenger of the gods, identifiable by the winged cap on his head. With the traditional pipes, and he is either half drawing or sheathing a Roman sword. Over a small turret on the opposite side of the tower is a gold vane of a pen bending a sword.

At various places on the monument are quotations appropriate to the art of war correspondence. These are from a great variety of sources beginning with Old Testament verses. Perhaps the most striking feature of all are the tablets inscribed with the names of 157 correspondents and war artists who saw and described in narrative and picture almost all the events of the four years of the war.

According to later historians who tried to verify this, some say Townsend’s account errs in that “Speed” and “Heed” appear under the heads of Electricity and Poetry, and the “statue of Pan” is actually a zinc copy of Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Mercury About to Kill Argos, created by the J.W. Fiske Company.

Although Townsend retained ownership of the property until his death in 1914, maintenance of the monument itself was entrusted to the War Department in 1904 and then the National Park Service after it was created in 1916.

The monument’s plaques lists 157 names which are sometimes assumed to be all war correspondents.

In the late 1990s, local historian Timothy J. Reese analyzed the list and asserted that only 135 can claim to be war correspondents or artists, and 33 of those are not identifiable in the historical record. Furthermore, many names are misstated and several important names are missing.

Unchanged for over a century, the arch had four names added in 2003: David Bloom, Michael Kelly, Elizabeth Neuffer and Daniel Pearl, according to Wikipedia.

The Gapland estate is now Gathland State Park. Several buildings still stand, including Gapland Hall (which is the park headquarters) and the mausoleum.

Townsend left Gapland in 1911, and died three years later in New York City. He was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia. The site was given to the State of Maryland and in 1949 became Gathland State Park.

After Matter

In his book, THE LIFE, CRIME, AND CAPTURE OF JOHN WILKES BOOTH, available for free in the public domain at Project Gutenberg, Townsend described the assassination of Lincoln and the escape of John Wilkes Booth.

The curtain had arisen on the third act, Mrs. Mountchessington and Asa Trenchard were exchanging vivacious stupidities, when a young man, so precisely resembling the one described as J. Wilkes Booth that be is asserted to be the same, appeared before the open door of the President’s box, and prepared to enter.

The servant who attended Mr. Lincoln said politely, “this is the President’s box, sir, no one is permitted to enter.” “I am a senator,” responded the person, “Mr. Lincoln has sent for me.” The attendant gave way, and the young man passed into the box.

As he appeared at the door, taking a quick, comprehensive glance at the interior, Major Rathbone arose. “Are you aware, sir,” he said, courteously, “upon whom you are intruding? This is the President’s box, and no one is admitted.” The intruder answered not a word. Fastening his eyes upon Mr. Lincoln, who had half turned his head to ascertain what caused the disturbance, he stepped quickly back without the door.

Without this door there was an eyehole, bored it is presumed on the afternoon of the crime, while the theater was deserted by all save a few mechanics. Glancing through this orifice, John Wilkes Booth espied in a moment the precise position of the President; he wore upon his wrinkling face the pleasant embryo of an honest smile, forgetting in the mimic scene the splendid successes of our arms for which he was responsible, and the history he had filled so well.

The cheerful interior was lost to J. Wilkes Booth. He did not catch the spirit of the delighted audience, of the flaming lamps flinging illumination upon the domestic foreground and the gaily set stage. He only cast one furtive glance upon the man he was to slay, and thrusting one hand in his bosom, another in his skirt pocket, drew forth simultaneously his deadly weapons. His right palm grasped a Derringer pistol, his left a dirk.

Then, at a stride, he passed the threshold again, levelled his arm at the President and bent the trigger.

A keen quick report and a puff of white smoke,—a close smell of powder and the rush of a dark, imperfectly outlined figure,—and the President’s head dropped upon his shoulders: the ball was in his brain.

The movements of the assassin were from henceforth quick as the lightning, he dropped his pistol on the floor, and drawing a bowie-knife, struck Major Rathbone, who opposed him, ripping through his coat from the shoulder down, and inflicting a severe flesh wound in his arm. He leaped then upon the velvet covered balustrade at the front of the box, between Mrs. Lincoln and Miss Harris, and, parting with both hands the flags that drooped on either side, dropped to the stage beneath. Arising and turning full upon the audience, with the knife lifted in his right hand above his head, he shouted “Sic, semper tyrannis—Virginia is avenged!” Another instant he had fled across the stage and behind the scenes. Colonel J. B. Stewart, the only person in the audience who seemed to comprehend the deed he had committed, climbed from his seat near the orchestra to the stage, and followed close behind. The assassin was too fleet and too desperate, that fury incarnate, meeting Mr. Withers, the leader of the orchestra, just behind the scenes, had stricken him aside with a blow that fortunately was not a wound; overturning Miss Jenny Gourlay, an actress, who came next in his path, he gained, without further hindrance, the back door previously left open at the rear of the theater; rushed through it; leaped upon the horse held by Mr. Spangler, and without vouchsafing that person a word of information, rode out through the alley leading into F street, and thence rapidly away. His horse’s hoofs might almost have been heard amid the silence that for a few seconds dwelt in the interior of the theater.

Then Mrs. Lincoln screamed, Miss Harris cried for water, and the full ghastly truth broke upon all—”The President is murdered!” The scene that ensued was as tumultuous and terrible as one of Dante’s pictures of hell. Some women fainted, others uttered piercing shrieks, and cries for vengeance and unmeaning shouts for help burst from the mouths of men. Miss Laura Keene, the actress, proved herself in this awful time as equal to sustain a part in real tragedy as to interpret that of the stage. Pausing one moment before the footlights to entreat the audience to be calm, she ascended the stairs in the rear of Mr. Lincoln’s box, entered it, took the dying President’s head in her lap, bathed it with the water she had brought, and endeavoured to force some of the liquid through the insensible lips. The locality of the wound was at first supposed to be in the breast. It was not until after the neck and shoulders had been bared and no mark discovered, that the dress of Miss Keene, stained with blood, revealed where the ball had penetrated.

This moment gave the most impressive episode in the history of the Continent.

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal.

Really enjoyed this article; interesting to read Townsend’s account of the assassination. Amazing what (not so little) tidbits of history there are around these parts. Crushing bike ride for Brooks, too!