By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Ida is a feminine given name found in Europe and North America, also popular in Scandinavian countries, where it is pronounced Ee-da. The name has an ancient Germanic etymology meaning “industrious” or “prosperous” and derives from the Germanic root id meaning “labor, work.”

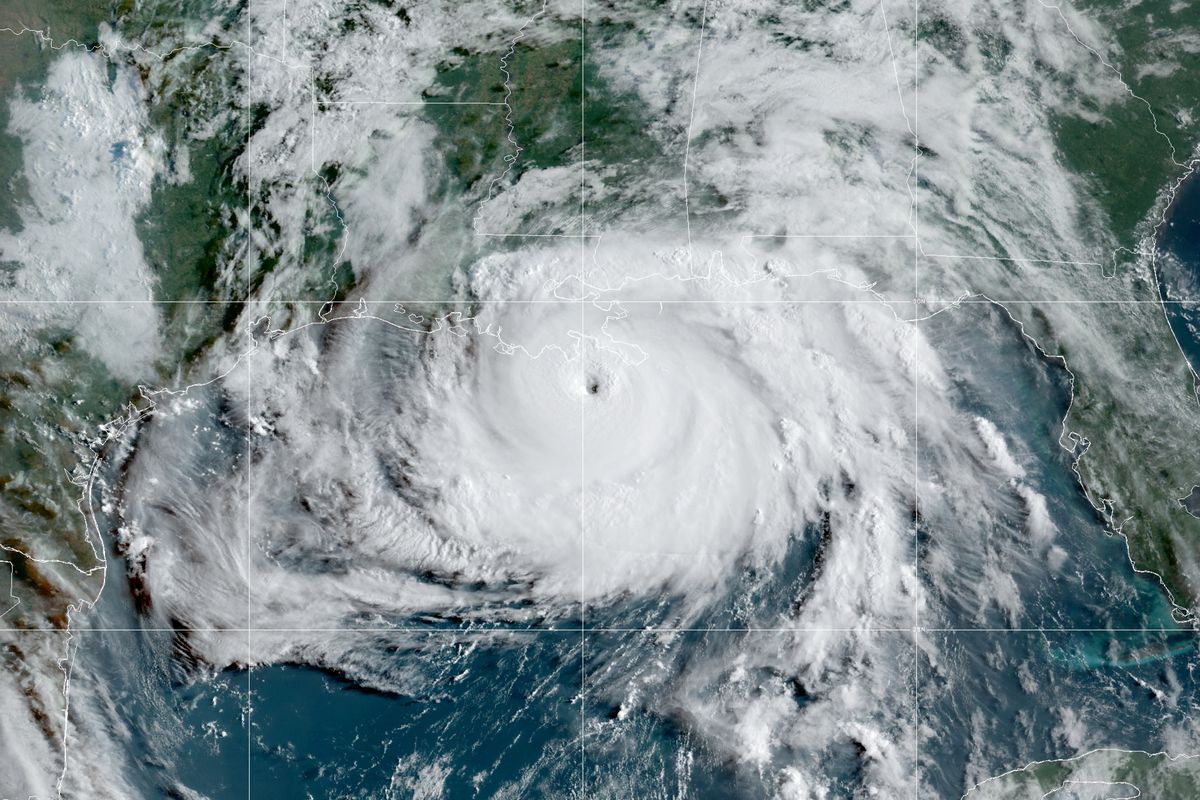

Clearly the National Hurricane Center, part of the federal National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, didn’t have hard work in mind when Ida was picked as the name for the tropical storm that slammed into Louisiana on Sunday and Monday as a category 4 hurricane on the 16th anniversary of Katrina. But maybe it fits.

Katrina was one of the most memorable and defining storms of the Anthropocene Epoch, an unofficial unit of geologic time describing the most recent period in Earth’s history when human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems.

Ida may not be as memorable as Katrina, since most of the levees around New Orleans seemed to hold, preventing the massive flooding and death seen live on CNN during and after Katrina.

While battling the Caldor Fire, a firefighter sprays water as crews burn vegetation to create a control line along Highway 50 in Eldorado National Forest, Calif., on Thursday, Aug. 26, 2021: Noah Berger

Ida also came on the same day the last of American troops exited Afghanistan, and as the California resort town of Lake Tahoe was destroyed by the Caldor fire, straining not only the resources of firefighters but also the resources of news outlets to cover all the big stories at once.

It was also the day 100,000 people were hospitalized for the first time in a year due to Covid as the Delta variant spreads like a wildfire in the unvaccinated population.

So much news. So little time.

With sustained winds of about 150 mph, Ida ripped roofs off buildings and snapped power poles and major transmission towers, knocking out cell phone and 911 services even as emergency first responders and hospitals were already overfull and overstretched by Covid. Ida also pushed a wall of water powerful enough to sweep homes off foundations and tear boats and barges from their moorings, even reversing the flow of the Mighty Mississippi River and trapping flood waters inland.

According to science coverage repeated on NPR, global warming from the burning of fossil fuels for energy leads to climate change, which played a role in how Ida rapidly gained strength right before it made landfall. It jumped from a Category 1 to a Category 4 storm in about 24 hours as it moved over abnormally warm water in the Gulf of Mexico.

The sea was measured by NOAA at about 85 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature of bathwater, a few degrees hotter than average. That additional heat acted as fuel for the storm.

“Heat is energy, and hurricanes with more energy have faster wind speeds and larger storm surges,” climate scientists say. “As the Earth heats up, rapidly intensifying major hurricanes such as Ida are more likely to occur.”

The trend is particularly apparent in the Atlantic Ocean system, which includes storms such as Ida that travel over the warm, shallow water of the Caribbean Sea and into the Gulf. A 2019 study found that hurricanes that form in the Atlantic are more likely to get powerful very quickly.

Residents along the U.S. Gulf Coast have been living with that climate reality for years. Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Hurricane Michael in 2018 and Hurricane Laura in 2020 all intensified rapidly before they made landfall. Ida now joins the list.

Hurricanes such as Ida are extra dangerous because there’s less time for people to prepare. By the time the storm’s power is apparent, it can be too late to evacuate.

Abnormally hot water also increases flood risk from hurricanes. Hurricanes suck up moisture as they form over the water and then dump that moisture as rain. The hotter the water — and the hotter the air — the more water vapor gets taken up by the storm.

Even areas far from the coast are at risk from flooding. Parts of central Mississippi and Southwest Alabama could receive up to a foot of rain, and forecasters are warning residents in Ida’s northeastward path to the mid-Atlantic region that they should prepare for dangerous amounts of rainfall and flash flooding.

Climate scientists agree broadly on one thing for sure, according to coverage in the New York Times: Global warming is changing the climate and the nature of storms.

Studies show that unusually warm Atlantic surface temperatures increase storm activity.

“It’s very likely that human-caused climate change contributed to that anomalously warm ocean,” said James P. Kossin, a climate scientist with the NOAA. “Climate change is making it more likely for hurricanes to behave in certain ways.”

For many years these changes have been predicted, and we are now seeing this reality play out right before our very eyes. There is no longer any room for political disagreement or religious doubt.

Higher Winds

There’s a solid scientific consensus that hurricanes are becoming more powerful, with higher winds.

Hurricanes are complex systems, but one of the key factors that determines how strong a storm ultimately becomes is ocean surface temperature. Warmer water provides more of the energy that fuels storms.

“Potential intensity is going up,” said Kerry Emanuel, a professor of atmospheric science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “We predicted it would go up 30 years ago, and the observations show it going up.”

Stronger winds mean downed power lines, damaged roofs and, when paired with rising sea levels, worse coastal flooding.

“Even if storms themselves weren’t changing, the storm surge is riding on an elevated sea level,” Dr. Emanuel said.

He used New York City as an example, where sea levels have risen about a foot in the past century.

“If Sandy’s storm surge had occurred in 1912 rather than 2012,” he said, “it probably wouldn’t have flooded Lower Manhattan.”

More Rain

Warming also increases the amount of water vapor the atmosphere can hold. In fact, every degree Celsius of warming allows the air to hold about 7 percent more water.

That means we can expect future storms to unleash higher amounts of rainfall.

Slower Storms

Researchers do not yet know why storms are moving more slowly, but they are. Some say a slowdown in global atmospheric circulation, or global winds, could be partly to blame.

In a 2018 research paper, Dr. Kossin found that hurricanes over the U.S. had slowed 17 percent since 1947. Combined with the increase in rain rates, storms are causing a 25 percent increase in local rainfall, he said.

Slower, wetter storms also worsen flooding. Dr. Kossin likened the problem to walking around your back yard while using a hose to spray water on the ground. If you walk fast, the water won’t have a chance to start pooling. But if you walk slowly, he said, “you’ll get a lot of rain below you.”

Wider-Ranging Storms

Because warmer water helps fuel hurricanes, climate change is enlarging the zone where hurricanes can form.

There’s a “migration of tropical cyclones out of the tropics and toward subtropics and middle latitudes,” Dr. Kossin said. That could mean more storms making landfall in higher latitudes, like in the U.S. or Japan.

More Volatility

As the climate warms, researchers also say they expect storms to intensify more rapidly. Researchers are still unsure why it’s happening, but the trend appears to be clear.

In a 2017 research paper based on climate and hurricane models, Dr. Emanuel found that storms that intensify rapidly — the ones that increase their wind speed by 70 miles per hour or more in the 24 hours before landfall — were rare in the period from 1976 through 2005. On average, he estimated, their likelihood in those years was equal to about once per century.

By the end of the 21st century, he says, those storms might form once every five or 10 years.

“It’s a forecaster’s nightmare,” Dr. Emanuel said.

If a tropical storm or Category 1 hurricane develops into a Category 4 hurricane overnight, he said, “there’s no time to evacuate people.”

There you have it. The climate science of hurricanes in a nutshell.

Believe it? Or not.

Now what to do about it?

We will cover that in a future story.

If you support truth in reporting, and fearless writing, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or PayPal.