By Glynn Wilson –

SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK, Va. — How do you tell the difference between a black bear and a grizzly?

Don’t try this at home or in a national park.

Sneak up on the bear and kick it in the rump, then run and climb a tree.

If the bear climbs up the tree after you, it’s probably a black bear. If it’s a grizzly bear, you would not make it to the tree.

This is a story not only told in folklore by national park naturalists. It even makes its way into the scientific literature on the American black bear (Ursus americanus), a medium-sized bear endemic to North America.

These days, we might add another story. If you get close enough to take a picture of the bear with your cell phone camera, it’s probably a black bear. Not that this is advisable. I use a very long camera lens.

Even though black bears are not that rare to see in mountainous areas in North America, there is still a fascination on the part of humans to see them. It is often among the first questions asked of national park rangers in places like Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. When they are sighted near campgrounds or along Skyline Drive, they can cause a “Bear Jam,” a traffic jam caused by a bear sighting.

After a year of hiding out from the coronavirus and the Boogaloo Bois, I made it up into the mountains last week and sure enough, a visitor asked a ranger by the campground office about bear sightings.

If only to prove that salacious rumors and misinformation are still alive and well in post-Trump America, probably being spread over the internet and social media — even among official government sources — the young ranger told the visitor that the bears were being hunted without a permit by local hunters because of an outbreak of the mange in the bear population.

“That’s the only way to get rid of the mange, to kill the bears,” this ranger said.

Further checking with official sources proved this rumor to be not true, at least not officially, however, so here is the real story.

When I asked a couple of other rangers about this issue, two said this was the first they had heard of it. So I followed up with emails and phone calls to higher up park officials.

In a telephone interview with Shenandoah National Park biologist Rolf Gubler, mange in bears has been on the rise in recent years, and officially park wildlife officials identify about seven to nine cases a year. But the National Perk Service is doing nothing to intervene or get involved in managing the problem in the wildlife, per the official policy of the U.S. Department of the Interior, with the exception of a couple of bears found so sick they had to be euthanized.

“Hunting of bears is strictly prohibited in the park,” Shenandoah wildlife management specialist Sally Hurlbert said in an email interview. “Hunting is allowed outside of the park during specific seasons and under the rules and regulations of Virginia.”

Sarcoptic mange, caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei mite, is a type of skin disease. Colloquially called “the mange,” it is characterized by the poor condition of the hairy coat due to the infection. The mites burrow into the outer layer of the skin and form tunnels. Female mites lay eggs within the tunnels, and within three days, larvae hatch and either move in the tunnels, or move to the surface of the infected animal’s skin. Within days, the larvae develop into nymphs, which then develop into adult mites — and repeat the cycle. Manage treatment can be difficult since larvae, nymphs, and adults can all be living on the same host in different life stages.

The Fish and Wildlife Service, also part of the Interior Department, has treated bears for mange in a few places, by trapping the bears or putting them to sleep with a tranquilizer dart and using medication that kills the mites, anti-parasitic drugs and antibiotics.

But not in Shenandoah National Park, according to official sources.

Searches for articles about this in local newspapers turned up nothing, but there are promotional style stories out there about how healthy the black bear population is in Virginia.

Related: Virginia’s black bears are flourishing. Officials have the bear teeth to prove it.

“For the past few decades, thanks to reforestation and state management, the black bear has become more and more common in the commonwealth. And while population estimates aren’t an exact science, relying as they do on factors like hunting data and human-bear interactions, one Virginia wildlife official puts the current count at between 18,000 and 20,000,” according to the Virginia Mercury.

“Surveys show bears are very popular. Citizens like bears. They want to have bears,” said Nelson Lafon, the Forest Wildlife Program manager for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

One indicator of how many bears there are in Virginia is contained in records on how many bears hunters killed during the permitted season. In 2020-21, 3,464 black bears were reported killed by hunters, the second-highest harvest on record.

“We knew we had a healthy bear population, so why not let hunters enjoy the resource?” Lafon told the local newspaper reporter, who reported that black bears are Virginia’s largest land mammal, capable of living in the wild for 30 years or more and typically ranging from 175 to 400 pounds. The species has no natural predators but also doesn’t tend to reproduce at a particularly fast rate.

For three centuries after Europeans first showed up on the East Coast, Virginia’s black bear population fell as a result of overhunting, deforestation due to agriculture, iron smelting and railroads and a blight that killed one of the species’ primary food sources, chestnuts.

Things changed at the turn of the 20th century, as farms with exhausted soils were abandoned and forestland returned. Then the national park system was created, leading to about 1.7 million acres of protected forest land in Virginia. The state instituted harvest controls with hunting seasons and restrictions on killing female bears, responsible for continuance of the species.

The conservation efforts were so successful that in 2017, the Department of Wildlife Resources (then called the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries) changed the regulations to reduce the black bear population, since more people reported seeing them in their yards, their garbage, even killing their dogs.

“We have a healthy bear population. It has been growing,” said Lafons. But “it’s too early to say whether these changes have started effecting a decrease in the places we want it to happen.”

Beginning in 1991, part of the data collection effort required all hunters to report to special bear checking stations where a “small premolar tooth” was extracted for officials to determine the age of the bears. Lafon claimed the compliance rates was about 75 percent, although officials know there are examples of poaching not caught by wildlife game rangers.

Gubler admitted that local hunters sometimes get away with poaching, even on park land — surrounded by private land — although he tends to think the problem has gone down in recent years rather than up, since there are fewer reports of people hunting bears for paws or their gallbladders, a trend from a few years ago.

“You just don’t hear much about that anymore,” he said.

But how do officials know for sure that local gun owners are not killing bears without permits on public land and spreading the rumor on social media? They don’t. There are not that many game wardens out there anymore, and even if there were, they would be connected up with locals in politics and church, and may not turn them in.

Facts About Black Bears

The American black bear is the continent’s smallest and most widely distributed bear species, constant throughout most of the Northeast and within the Appalachian Mountains almost continuously from Maine to northern Georgia, the northern Midwest, the Rocky Mountain region, the West Coast and Alaska. It seems to have expanded its range during the past decade, with recent sightings in Ohio, Iowa and southern Indiana.

Surveys taken from 35 states indicate that the black bear population is either stable or increasing, except in Idaho and New Mexico. The overall population of American black bears in the United States has been estimated to range between 339,000 and 465,000, though this excludes populations from Alaska, Idaho, South Dakota, Texas and Wyoming, whose population sizes are unknown. In the state of California, there are an estimated 25,000-35,000 American black bears, making it the largest population of the species in the contiguous United States.

There are about 1,500 bears in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, at all elevations, a density of about two per square mile.

Black Bear Diet

Black bears are mostly omnivores living in forested areas, but will leave forests in search of food, and they will eat meat, including white-tailed deer fawns. About 85 percent of the black bear’s diet consists of vegetation, biologists say, though they tend to dig less than brown bears, eating far fewer roots, bulbs, corms and tubers.

When initially emerging from hibernation in the spring, they will seek to feed on carrion from winter-killed animals or newborn hoofed mammals like pigs, cattle or deer. Bears may catch the scent of hiding fawns when foraging for something else and then sniff them out and pounce on them. As the fawns get up on their legs and are able to run by 10 days of age, they can outmaneuver the bears. American black bears have also been recorded similarly preying on elk calves in Idaho and moose calves in Alaska.

In Shenandoah National Park, a unique place where the bear populations have evolved for generations without being hunted, they tend to go after newborn fawns in areas near campgrounds, where the white-tailed deer mother does tend to drop them near humans to try to protect them from bears. I witnessed this phenomenon in person in May and June, 2015.

Related Coverage

Oh Shenandoah in Spring: How the Fawns Escape the Bears

Yearling Bear Named ‘Boo Boo’ Chooses Awkward Glade at Big Meadows in Shenandoah National Park

In summer, the black bear diet consists largely of fruits, especially wild apples and berries in Shenandoah. In autumn, feeding becomes virtually the full-time task of bears. They like nuts such as hazelnuts, oak acorns and whitebark pine nuts, and they are known to raid the nut caches of tree squirrels. Bears living in areas near human settlements or around a considerable influx of recreational human activity often come to rely on foods inadvertently provided by humans, including garbage, birdseed and agricultural products.

Bears also eat insects, including bees, ants and their larvae, although just like the fairy tales and cartoons, black bears are also fond of honey. They will gnaw through trees if hives are too deeply set into the trunks for them to reach it with their paws. Once the hive is breached, the bears will scrape the honeycombs together with their paws and eat them, seemingly oblivious of bee stings.

Where available, mainly in the West, black bears also fish for salmon. But unlike grizzlies, they tend to fish at night since their black fur is easily spotted by salmon in the daytime.

Bear Hibernation

American black bears were once not considered true or “deep” hibernators, but because of discoveries about the metabolic changes that allow American black bears to remain dormant for months without eating, drinking, urinating or defecating, most biologists have redefined mammalian hibernation as “specialized, seasonal reduction in metabolism concurrent with scarce food and cold weather.” American black bears are now considered highly efficient hibernators.

During their time in hibernation, an American black bear’s heart rate drops from 40 to 50 beats per minute to 8 beats per minute.

Bear Attacks on People

Although an adult bear is quite capable of killing a human, American black bears typically avoid confronting humans. Unlike grizzly bears, which became a subject of fearsome legend among the European settlers of North America, black bears were rarely considered overly dangerous, even though they lived in areas where the pioneers had settled.

Black bears rarely attack when confronted by humans and usually only make mock charges, emit blowing noises and swat the ground with their forepaws.

Campers and hikers are told when encountering a black bear to “make themselves big” by standing tall, waiving their arms and yelling at the bears. Appalachian Trail hikers often carry bear spray just in case.

The number of attacks on humans is higher than those by brown bears in North America, but this is largely because black bears considerably outnumber brown bears. Compared to brown bear attacks, aggressive encounters with American black bears rarely lead to serious injury or death.

Most black bear attacks tend to be motivated by hunger rather than territoriality and thus victims have a higher probability of surviving by fighting back rather than submitting. Unlike female brown bears, female black bears are not as protective of their cubs and rarely attack humans in the vicinity of the cubs, altlough occasionally such attacks do occur. The worst recorded attack occurred in May 1978, in which an American black bear killed three teenagers fishing in Algonquin Park in Canada. Another exceptional attack occurred in August 1997 in Liard River Hot Springs Provincial Park in Canada, when an emaciated American black bear attacked a mother and child, killing the mother and a man who intervened. The bear was shot while mauling a fourth victim.

But there is already one reported death this year. Laney Malavolta, 39, was attacked and killed by a black bear on April 30, 2021, in Wild Durango, Colorado, while walking her dogs off of US 550, near Trimble. Her body showed signs of partial consumption. Authorities shot and killed a mother black bear and two cubs found nearby.

The majority of attacks happen in national parks, usually near campgrounds, where the bears habituated to close human proximity and food. Of 1,028 incidents of aggressive acts toward humans, recorded from 1964 to 1976 in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, 107 resulted in injury and occurred mainly in tourist hot spots where people regularly fed the bears handouts.

Bear Hunting

Historically, black bears were hunted by both Native Americans and European settlers. Some Native American tribes, in admiration for the American black bear’s intelligence, would decorate the heads of bears they killed with trinkets and place them on blankets. Tobacco smoke would be wafted into the disembodied head’s nostrils by the hunter that dealt the killing blow, who would compliment the animal for its courage

Currently, 28 of the U.S. states have American black bear hunting seasons. Nineteen states require a bear hunting license, with some also requiring a big game license. In eight states, only a big game license is required to hunt American black bears. Overall, over 481,500 American black bear hunting licenses are sold per year.

American black bear meat had historically been held in high esteem among North America’s indigenous people and colonists. According to the second volume of Frank Forester’s Field Sports of the United States, and British Provinces, of North America, “The flesh of the [black] bear is savoury, but rather luscious, and tastes not unlike pork. It was once so common an article of food in New-York as to have given the name of Bear Market to one of the principal markets of the city.”

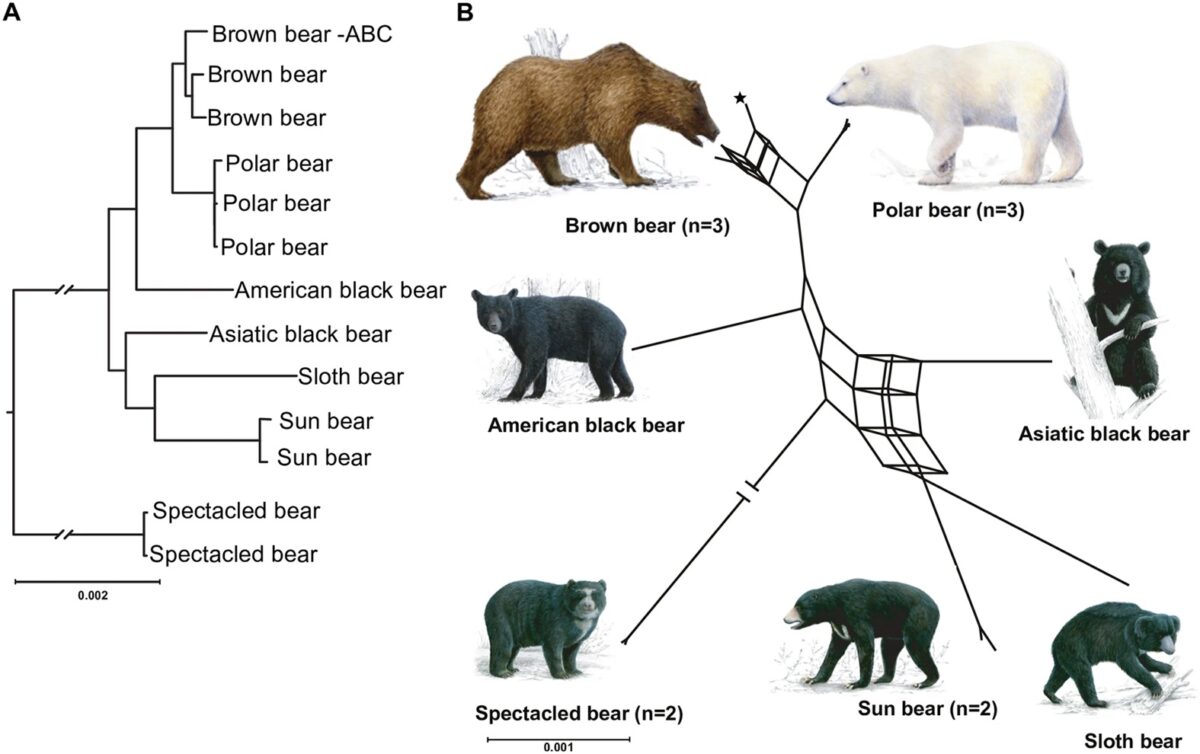

Bear Evolution

Bears are iconic mammals with a complex evolutionary history.

The evolution of bears as we know them today started around 30 million years ago. Their ancestors evolved into a family of small mammals known as the Miacids (Miacidae). The bears, small bears and also the canines developed from the Miacids. Some of the canine species resembled bears, and we refer to them as bear dogs or Amphicyonidae. The size and appearance of the bear dog varied from small and dog-like to big and bear-like. The family of real bears can ultimately be traced back to the oldest genus, the Ursavus, which was roughly the size of a sheepdog and had evolved from a canine ancestor.

In Folklore, Mythology and Culture

American black bears are featured prominently in the stories of some of America’s indigenous peoples. One tale tells of how the black bear was a creation of the Great Spirit, while the grizzly bear was created by the Evil Spirit.

Morris Michtom, the creator of the teddy bear, was inspired to make the toy when he came across a cartoon of Theodore Roosevelt refusing to shoot an American black bear cub tied to a tree.

The best advice from park rangers is to never feed the wildlife, and avoid getting too close, especially by trying to take pictures with a cell phone.

More Photos