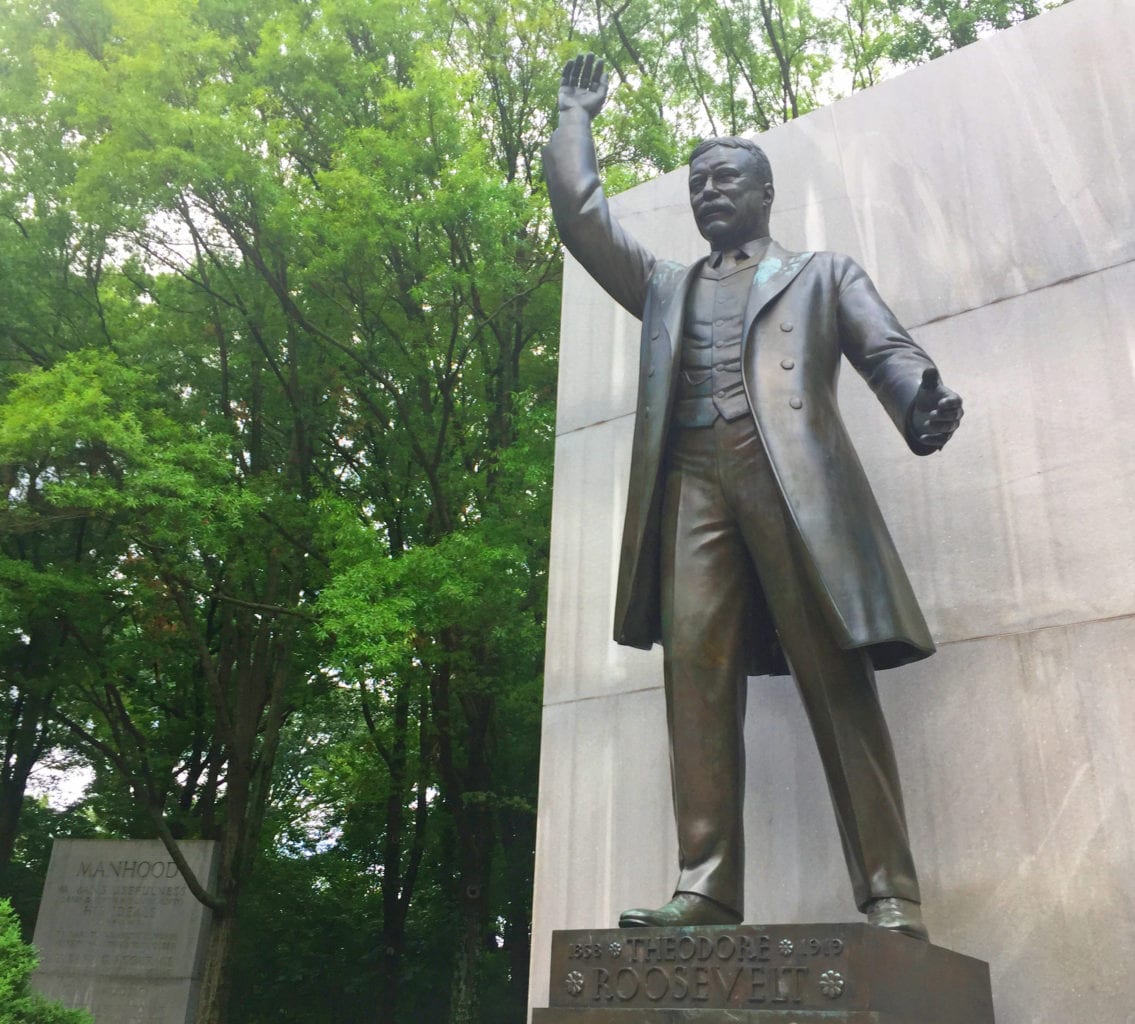

A statue of Teddy Roosevelt on Theodore Roosevelt Island, a presidential living memorial: Glynn Wilson

Secret Vistas –

By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Lurking on a wooded little island in the Potomac River just across the water from Georgetown, there lie important lessons for progressive Democrats from the most progressive president in American history.

In continuing our exploration of the U.S. capital region, not just the partisan politics, we ventured over the river to Virginia this week and took a hike in the woods and a swim from a beach on Theadore Roosevelt Island administered by the National Park Service as part of the George Washington Parkway.

It’s far from the most visited monument in the area, with only about 168,195 visitors a year, probably in part because you must walk across a bridge to see it and bicycles are not allowed. Compare that to the most visited monument in Washington, the Lincoln Memorial, with 7.9 million visitors each year.

But the point is not just arriving at the destination or even the journey. It’s what we can learn from it.

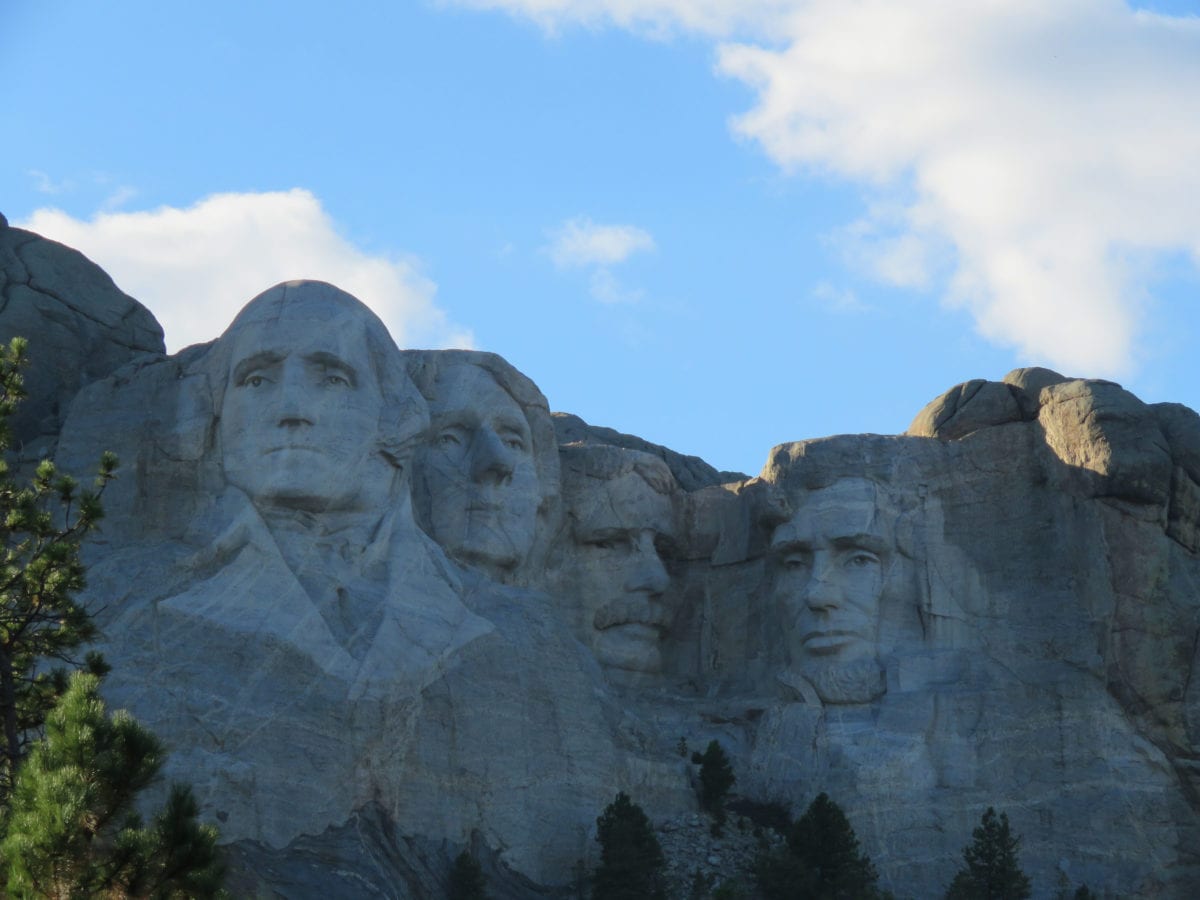

“Teddy” Roosevelt hated the name Teddy, and was not enthralled when capitalists created the Teddy Bear named after him because of an encounter with a bear on a hunting trip to Mississippi in 1902. His face is carved into Mount Rushmore along with George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson in part because he was a very famous personage who historians rate in the top five presidents in U.S. history.

In researching his background, there is much to like about Roosevelt, if not everything.

A Square Deal

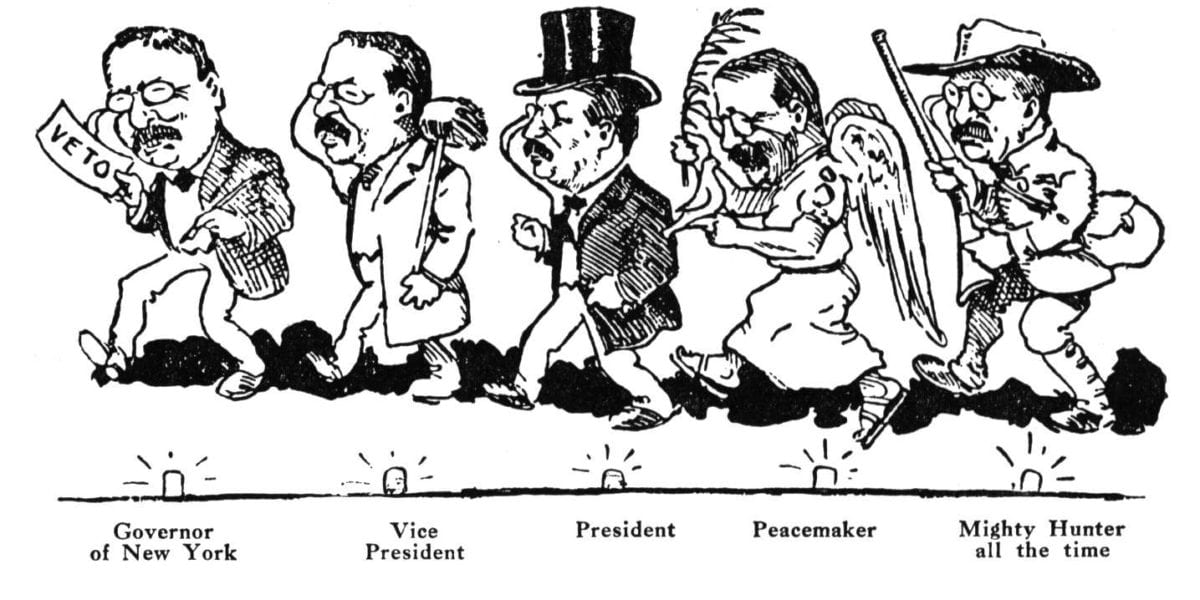

I think we would do well to remember his primary philosophy for governing, what he called a “Square Deal,” something he came up with as governor of New York and took with him to the White House as Vice President. He became president in 1901 after President William McKinley died in office, and was overwhelmingly elected to a second term in 1904.

According to historians, his philosophy “rested firmly upon the concept of the square deal by a neutral state.” The rules for the Square Deal were “honesty in public affairs, an equitable sharing of privilege and responsibility, and subordination of party and local concerns to the interests of the state at large.”

He took on the large corporations at the time, the railroads, steel and oil companies and helped organized labor, insisting on “public responsibility” for companies. But he is probably best known and remembered for his love of nature and the outdoors and his conservation efforts, which were substantial.

Conservation

Of all Roosevelt’s achievements, he was proudest of his work in the conservation of natural resources, extending federal protection to special lands and wildlife. Roosevelt worked closely with Interior Secretary James Rudolph Garfield and Chief of the U.S. Forest Service Gifford Pinchot to enact a series of conservation programs that often met with resistance from Western members of Congress, most especially Charles William Fulton. Roosevelt established the Forest Service as a federal agency to manage public lands, and promoted and signed laws that created five new national parks. He signed the 1906 Antiquities Act, creating 18 new national monuments. He also established the first 51 bird reserves, four game preserves, and 150 national forests.

Roosevelt was one of the first presidents to use executive orders to protect public lands, and by the end of his second term in 1909, he had established 150 million acres of forest land reserves.

A Friend to Workers

When coal miners went on strike in 1902, threatening a national energy shortage, Roosevelt threatened the coal companies with intervention by federal troops, taking on the powerful J.P. Morgan. He helped negotiate an arbitration agreement that ended the strike and resulted in higher pay and limits on working hours for miners.

He also took on the powerful railroads by fighting for and passing the 1906 Hepburn Act, which gave the Interstate Commerce Commission the power to regulate rates, pipeline fees and storage contracts.

He took on the food packing industry by pushing Congress to pass the Meat Inspection Act of 1906 and the Pure Food and Drug Act. Though conservatives initially opposed the bill, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, published in 1906, helped galvanize support for reforms and regulations. The Meat Inspection Act banned misleading labels and preservatives containing harmful chemicals. The Pure Food and Drug Act banned food and drugs that were impure or falsely labeled from being made, sold and shipped.

Foreign Policy

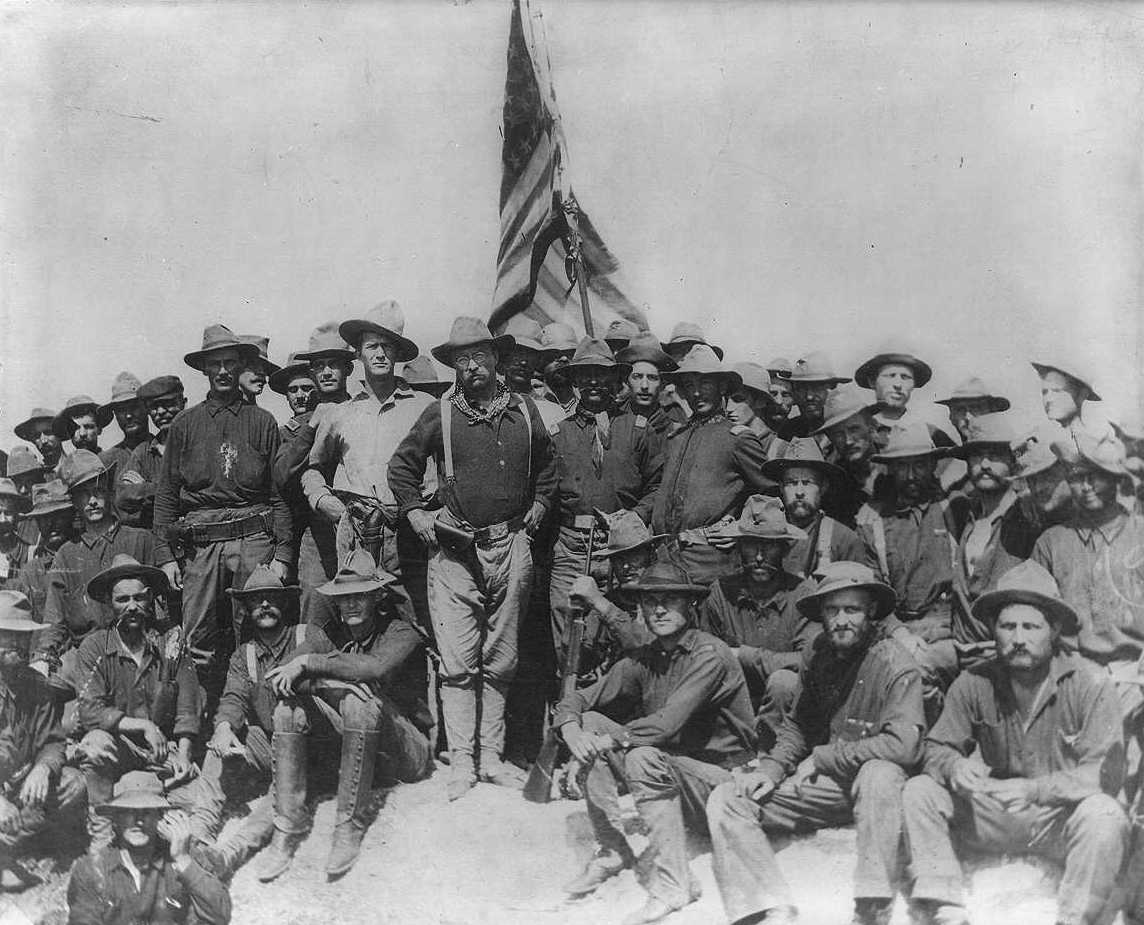

While many school children learn the story of Roosevelt’s volunteer calvary called the “Rough Riders” who fought against Spain in Cuba during the Spanish-American war, including his charge on his horse Little Texas up San Juan Hill, a story that helped make him famous, it is important to remember that the U.S. emerged from that conflict as a bona fide world power and that influenced Roosevelt’s thinking. His tendency was to push for American empire and imperialism in Asia, South America and the Caribbean, but his views moderated over time.

While he vigorously defended the permanent acquisition of the Philippines and expansion in Asia in the 1890s, and the building of the Panama Canal was considered his pet project, he ended up negotiating treaties with Japan and Russia, and Great Britain, during his tenure. He did drastically increase the size of the navy, and he took on Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm, Italy and the British in Venezuela and wrote something that came to be called the “Roosevelt Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, protecting American interests in the Western Hemisphere.

“Chronic wrongdoing or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere, the adherence of the United States to the Monroe doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.”

Roosevelt was accused of corruption during the building of the Panama Canal, but it was never proven and he denied it and even sued Joseph Pulitzer’s sensational New York World and the Indianapolis News for libel. He lost those cases, and otherwise was considered a friend of the press who held daily press briefings as president and created the first press room in the White House. He had made a living as a writer and magazine editor before becoming president, and he loved discussions with intellectuals, authors and writers. Yet it is said he drew the line at expose-oriented “scandal-mongering” journalists who, during his terms, set magazine subscriptions soaring with their attacks on corrupt politicians, mayors and corporations. He made a speech in 1906 giving us the term “muckraking journalist.”

“The liar,” he said, “is no whit better than the thief, and if his mendacity takes the form of slander he may be worse than most thieves.”

During his 1904 election campaign, he was also criticized by Democrats for being too cozy with corporate interests. Even then the big corporations were known for funneling millions of dollars in campaign cash to the Republican Party, although it was a much different party back then. Remember, the Republican Party was the party of Lincoln, which opposed the South in the Civil War to preserve the union and freed the slaves.

Roosevelt strongly denied the accusations that he was a tool of big business, saying he would “go into the Presidency unhampered by any pledge, promise, or understanding of any kind, sort, or description…” He once again promised to give every American a “square deal.”

He won the election with 56 percent of the popular vote and 336 to 140 in the Electoral College, and he pledged not to serve a third term, warning against an American dictatorship.

As time went by during his second term, Roosevelt grew even more progressive, moving to the left of his Republican Party base and called for a series of reforms, most of which failed to pass Congress. His influence on the wane due to his lame duck status and a backlash from Congress, Roosevelt tried to pass a national incorporation law for corporations, which were only regulated by states at the time, and he called for a federal income tax and an inheritance tax. He called for limits on the use of court injunctions against labor unions during strikes and he wanted an employee liability law for industrial injuries and an eight-hour work day for federal employees. He advocated for a postal savings system to provide competition for local banks, and he pushed for campaign reform laws.

Congress did not go along. Some of these plans came to fruition in the 1930s during the Great Depression and the tenure of his distant cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Republican William Howard Taft succeeded Roosevelt in the White House in the election of 1908, defeating the populist Democrat William Jennings Bryan in his third and final attempt to be president. Taft promoted a progressivism that stressed the rule of law, but he proved to be a less adroit politician than Roosevelt and lacked the energy and personal magnetism, along with the publicity devices, the dedicated supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so formidable.

When Roosevelt realized that lowering tariffs would risk creating severe tensions inside the Republican Party by pitting producers (manufacturers and farmers) against merchants and consumers, he stopped talking about the issue. But Taft took on a disastrous trade war.

In an effort to get out of the way and let Taft be his own man, Roosevelt set out to tour Europe and Africa, where he hunted for specimens for the Smithsonian Institution and for the American Museum of Natural History. While he was criticized for it, his party killed or trapped approximately 11,400 animals from insects and moles to hippopotamuses and elephants. The 1,000 large animals included 512 big game animals, including six rare white rhinos. Tons of salted animals and their skins were shipped to Washington, and it took many years to mount them all.

“I can be condemned only if the existence of the National Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, and all similar zoological institutions are to be condemned,” he said in response to the criticism. He published a book on the trip called African Game Trails, recounting the excitement of the chase, the people he met, and the flora and fauna he collected “in the name of science.”

In Europe, Roosevelt refused a meeting with the Pope due to a dispute over a group of Methodists active in Rome, but met with Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, King George V of Great Britain, and other European leaders. In Oslo, Norway, Roosevelt delivered a speech calling for limitations on naval armaments, a strengthening of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and the creation of a “League of Peace” among the world powers. He also delivered the Romanes Lecture at Oxford, in which he denounced those who sought parallels between the evolution of animal life and the development of society, what came to be called “social Darwinism” or “eugenics.”

Still fairly young and healthy, Roosevelt had not lost all political ambition. He became disillusioned with Taft, in part over his position on tariffs, and in November 1911, a group of Ohio Republicans endorsed Roosevelt for the party’s nomination for president.

“I am really sorry for Taft…,” Roosevelt was quoted as saying. “I am sure he means well, but he means well feebly, and he does not know how! He is utterly unfit for leadership and this is a time when we need leadership.”

Presidential Primaries

The first extensive use of presidential primaries in American politics occurred in the 1912 elections, an achievement of the progressive movement of the day. But Taft was able to win the Republican nomination at the 1912 Republican National Convention in Chicago, even though Roosevelt expressed doubt about his prospects for victory against the Democrats in the general election. Even though Roosevelt was the first president to host a black man at dinner in the White House, Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Taft got black delegates from the South to oppose Roosevelt at the convention.

After he lost, Roosevelt announced that he would “accept the progressive nomination on a progressive platform and I shall fight to the end, win or lose.” At the same time, Roosevelt prophetically said, “My feeling is that the Democrats will probably win if they nominate a progressive.”

The party became known as the “Bull Moose Party,” after Roosevelt told reporters, “I’m as fit as a bull moose.”

The party’s platform called for vigorous government intervention to protect the people from the “selfish interests.” Clearly Vermont Senator and Presidential Candidate Bernie Sanders takes some of his campaign platform from Roosevelt, although he is hardly as popular with the American people.

“To destroy this invisible Government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day,” he said. “This country belongs to the people. Its resources, its business, its laws, its institutions, should be utilized, maintained, or altered in whatever manner will best promote the general interest. This assertion is explicit… Mr. (Woodrow) Wilson must know that every monopoly in the United States opposes the Progressive party… I challenge him… to name the monopoly that did support the Progressive party, whether… the Sugar Trust, the U.S. Steel Trust, the Harvester Trust, the Standard Oil Trust, the Tobacco Trust, or any other… Ours was the only program to which they objected, and they supported either Mr. Wilson or Mr. Taft.”

Though many Progressive Party supporters in the North were supporters of civil rights for African Americans, Roosevelt did not give strong support to civil rights and ran a “lily-white” campaign in the South, clearly a flaw and a mistake. Rival all-white and all-black delegations from four Southern states arrived at the Progressive national convention, and Roosevelt decided to seat the all-white delegations. He won little support outside mountain Republican strongholds. Out of nearly 1100 counties in the South, Roosevelt won two counties in Alabama, one in Arkansas, seven in North Carolina, three in Georgia, 17 in Tennessee, two in Texas, one in Virginia, and none in Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi or South Carolina.

On October 14, 1912, while campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Roosevelt was shot by a saloonkeeper named John Flammang Schrank. The bullet lodged in his chest after penetrating his steel eyeglass case and passing through a 50 page speech in his jacket pocket titled “Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual,” which is on display in Washington to this day. He delivered the speech with blood seeping into his shirt and spoke for 90 minutes before accepting medical attention. Probes and an x-ray showed that the bullet had lodged in Roosevelt’s chest muscle, but did not penetrate the chest membrane. Doctors concluded that it would be less dangerous to leave it in place than to attempt to remove it, so Roosevelt carried the bullet with him for the rest of his life.

Roosevelt’s warning about the Democrats turned prophetic, when the party nominated Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey. Many progressive Democrats who might have otherwise considered voting for Roosevelt helped elect Wilson with 42 percent of the popular vote and 435 electoral votes, a massive landslide in the Electoral College.

Roosevelt won 4.1 million votes (27%), compared to Taft’s 3.5 million (23%), and came away with a higher share of the popular vote than any other third party presidential candidate in American history.

After that loss he disembarked on a disastrous trip to South America, where he contracted malaria.

Back in New York, he did some work on a League of Nations, although it was Wilson who led the U.S. in World War I and set up the organization that was a precursor to the United Nations.

Death

On the night of January 5, 1919, Roosevelt suffered breathing problems. After receiving treatment from his physician, he said he felt better and went to bed. Roosevelt’s last words were “Please put out that light, James” to his family servant James Amos. Between 4 and 4:15 the next morning, Roosevelt died in his sleep at Sagamore Hill after a blood clot had detached from a vein and traveled to his lungs. He was 60.

Upon receiving word of his death, his son Archibald telegraphed his siblings: “The old lion is dead.”

Woodrow Wilson’s vice president, Thomas R. Marshall, said that “Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight.”

So he has a reputation as a macho man, not something that is politically correct in these times.

He apparently coined the phrase, “Speak Softly and Carry a Big Stick,” according to sources cited by Wikipedia, where you can find out more.

Find out more about Theodore Roosevelt Island here.

More Photos

A statue of Teddy Roosevelt on Theodore Roosevelt Island, a presidential living memorial: Glynn Wilson

A statue of Teddy Roosevelt on Theodore Roosevelt Island, a presidential living memorial: Glynn Wilson

Very good look at TR, Glynn!

The type of reporting that is drastically needed in mainstream media!

How we need Teddy Roosevelt today, as well as Gifford Pinchot. These were forward-thinking people, unwilling to destroy nature’s gifts for a quick buck. I am seeing promise in Bernie Sanders.

Excellent.