By Glynn Wilson –

Like many a fellow traveler before him inspired by the American landscape, Missouri country boy turned middle-aged Alabama forester Mark J. Hainds grew impatient with his life of teaching, raising a family, and conducting research to conserve and propagate the return of the longleaf pine forest in the South, long ago described by another researcher and adventurer, William Bartram in his travels.

Plagued by modern, suburban anxieties and frustrations, and no doubt inspired by John Muir, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn before him and admittedly Cormac McCarthy, Hainds set about to be the first to walk the entire Southern border of the United States.

While The Washington Post recently published an inaccurate story claiming two women were the first to hike all 1,954 miles of the border to find out just how dangerous it really is, Hainds had already beaten them and is working on a second book about his adventures from El Paso west to the Pacific Ocean in California, south of San Diego.

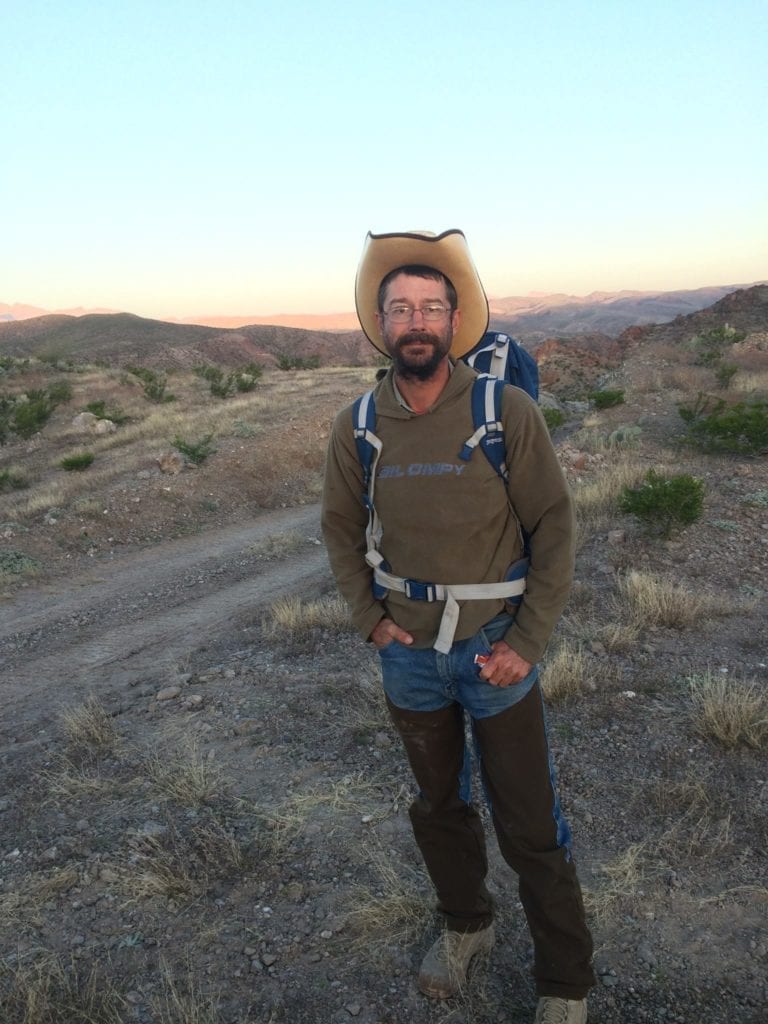

In the first major trek back in the fall of 2014, detailed in his book Border Walk, Hainds set out along the Rio Grande or Rio Bravo del Norte at the border between El Paso, Texas and Juarez, Mexico, and hiked more than 1,000 miles to Boca Chica Beach on the Gulf of Mexico by Christmas.

He endured the pains of walking 20 to 25 miles a day to test himself — and the dangers of feral hogs, wild dogs, rattlesnakes, tarantulas, scorpions, speeding trucks, border patrol agents and a few coyote drug smugglers or “drug mules.” He wanted to discover and experience the realities and culture of a region that has long been misunderstood and mischaracterized by politicians looking for an easy-to-exploit campaign diversion, some issue to rile up a constituency against an easy scapegoat, the Hispanic people.

While his personal quest was decided upon and mapped before Donald Trump jumped into the presidential race in 2015, the subject of building a wall between the U.S. and Mexico had been broached before by other Republicans, including Texas Senator Ted Cruz. Controversy along the border had simmered since the early 1990s about the time of the NAFTA treaty with Canada and Mexico. With no compromise ever emerging from Congress over the years on a reasonable immigration reform plan, the border controversy came to a head again after September 11, 2001, when the Bush administration included the Southern border in the “war on terrorism.”

While he does not get into all the reasons and timing in the book or the film of making the decision to do the walk, I got him to reveal it to me in an email interview.

“I was on I-10, somewhere around Tallahassee, (Florida) driving to another longleaf pine meeting somewhere in the Carolinas: can’t remember if it was NC or SC, and this idea hit me,” he said. “I was so excited (I) pulled over to call my contact (Beth Motherwell) with the University of Alabama Press (they published my 1st book) and told her about it.”

His first book was Year of the Pig, about hunting wild boar for environmental reasons, but also the best way to cook and eat them.

“Beth said, ‘As long as you don’t get killed, it should be an interesting topic’.”

The manuscript was rejected by UA Press in the end. One of two anonymous reviewers seemed to disagree with the point of view that building a wall is not necessary or wise, so Hainds ended up self-publishing the book. Peer review is not always without political bias.

“This was before Trump was on the radar as a potentially serious candidate,” he said. “There was talk about border security but that wasn’t what gave me the idea. Believe it or not, I attribute the genesis of this idea to Cormac McCarthy. My former boss loaned me a copy of All the Pretty Horses, and then I read and watched ‘No Country for Old Men.’ All Cormac’s stuff is set along the border, and it captured my imagination when I was looking for an escape route from my job/life at that time.

“I tell people, ‘This may sound macabre, because most everyone dies in Cormac McCarthy books, but his descriptions of the harsh-desolate West Texas landscapes drew me like a moth to the flame’.”

He reveals his tolerance of pain in his legs and feet in the book, a touch of an interest in danger if not a death wish, as well a nearly celebratory embrace of harsh weather at times, cold, rain, wind and heavy fog. It seemed to take his mind off mundane troubles back home, like bills, debt, “the daily grind,” and finding a new job.

He had the distinction as the first employee of the Longleaf Alliance, formed to ensure a sustainable future for the longleaf pine ecosystem through partnerships, landowner assistance and science-based education and outreach. And as a research associate at Auburn University, he was considered a leading academic expert on the artificial regeneration of longleaf. He spoke to thousands of people annually across the range of the pine from Virginia to Texas.

But when both founders of the Alliance retired and the organization became a non-profit, he said, they hired a business manager from a big paper company.

“We had different visions and their vision included me sitting behind a desk a lot more, with a lot more paperwork,” he told me.

In the book, Hainds laments the attitude about pine forests in the forestry “business,” where land managers and forestry agents were not so interested in recreating the park-like forests William Bartram wrote about in the late 1700s. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the longleaf was cut from North Carolina to Texas along with most of the other trees to make wood for a growing industrial economy.

“They are too focused on growing wood, often at the expense of diversity, aeshethics and wildlife,” Hainds writes.

Rex Jones went along for the journey to produce a film called La Frontera for The Southern Documentary Project and the Center for Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, which aired on PBS.

Tex-Mex Compadres

Traveling with an ad hoc cohort of friends to support him along the way called the Tex-Mex Compadres, they abided by an ethical and fun set of rules to govern his travels, including Rule No. 3: Don’t pass an open bar without taking a drink.

Rule No. 1: “Keep Mark Alive.”

Many people warned him not to do it and said he would never survive the trip, claiming the border region was so dangerous, “They will kidnap and kill you!” Friends and border patrol agents warned him along the way about certain roads, like Old Mines Road between Eagle Pass and Laredo, saying: “You can’t walk there. You will be killed. This is the last we will see of you.”

But that’s not what he found along a border he says may divide two countries, but unites two cultures, where he says a border wall will do more harm than good for the wildlife, the people and the culture.

“When confronted with the topography, people, and scale of the borderlands, one should realize that (the idea of) erecting a wall the length of the U.S.-Mexico border can best be described as paranoid, delusional, and grandiose,” Hainds concludes in the end. “If you prefer to live in urban areas but are worried about crime, move to a border town on the American side. It will probably be safer than where you currently reside.”

In another place in the book, Hainds writes that building a wall should be “anathema to libertarians.”

“For the government to erect a continuous wall would require invoking eminent domain on a grand scale,” he says. “…the pro-wall position is untenable in a world bounded and based in logic, geography and reality.”

All along the route, Hainds discovered clean, safe and prosperous cities like El Paso and quaint, happy communities, as well as a few near ghost towns, abandoned by the railroads. He met friendly, helpful and gracious people, who at times fed him, offered him clothing, rides and free places to stay, bought him drinks, and offered commentary and expertise on the history of the places along the way. He also interviews experts on the flora and fauna, including many birds and reptiles.

And yet, he fends off attacks from a wild boar, a wild-eyed dog and finds himself surprise witness to a drug deal going down in a remote area near the border, one of the scariest incidents along the trail. But he says the biggest threat he came across were speeding trucks barreling across narrow bridges over lakes and rivers along some of the less attractive, busy stretches of highway he traversed to make the journey. He called U.S. Highway 277 between Del Rio and Piedras Negras “terrifying” and the drivers there “the worst.”

While many people across the country and the world may think of Texas as a flat, desert landscape of cactus, snakes and tumbleweed, along the river, Hainds and Jones in the film describe mountain beauty and even Precambrian rock formations with no fossils since they predate life on earth.

While Hainds is no journalist, no Edward Abbey, John McPhee or Cormac McCarthy, as travel journals go, this is a good read and a worthy contribution to the literature of what we know of the Southern border.

“This expedition met and exceeded my personal objectives,” Hainds says in the end of the film as he makes it to the Gulf beach. “I tested myself physically and mentally. I got away from the anxieties and frustrations that were plaguing me. I changed my life’s direction by overcoming the inertia holding me back from other more rewarding paths.

“But what the walk really did was reveal the amazing character and humanity of those who call the border their home,” he says. “And in telling their story perhaps I will accomplish something bigger than I ever intended.”

If it does anything to illuminate why Trump’s border wall proposal is just a simple-minded political catch-phrase for offering red meat and a rallying cry for a conservative, even “racist” base of people to vote Republican, it will prove worth the blisters, blood, sweat and tears. If it does anything to help stop the further destruction of the borderlands and the defamation of its people, it will have been be a road worth taking indeed.

—

See some of the other reviews and stories written about the trip here.

Amazon.com: A Tale Told Well of a Long Walk along Today’s US & Mexican Border, by Johnny Stowe

AP: Fellow border travelers meet, in the middle of nowhere

Mark J. Hainds: The Border, It’s Not What You Think!

More Photos

Thank you Dearly for writing this Article, Glynn!

I have purchased and experienced the adventure of Border Walk AND have personally been fortunate enough to spend time with the Pioneer himself, Marcus Hainds.

The man is a Savant in the Science world, a Light in the Natural World and a truly Enlightened Spirit for seeking Truth!

I encourage EVERYONE to support his venture and READ HIS BOOK AND WATCH HIS DOCUMENTARY!

Border Walk:

https://www.amazon.com/Border-Walk-Mark-J-Hain…/…/0578201704

I also invite you to watch the Film Documentary devoted to his ventures and travels.

La Frontera:

https://vimeo.com/166957573

May we ALL Walk the Walk BEFORE we Talk the Talk…