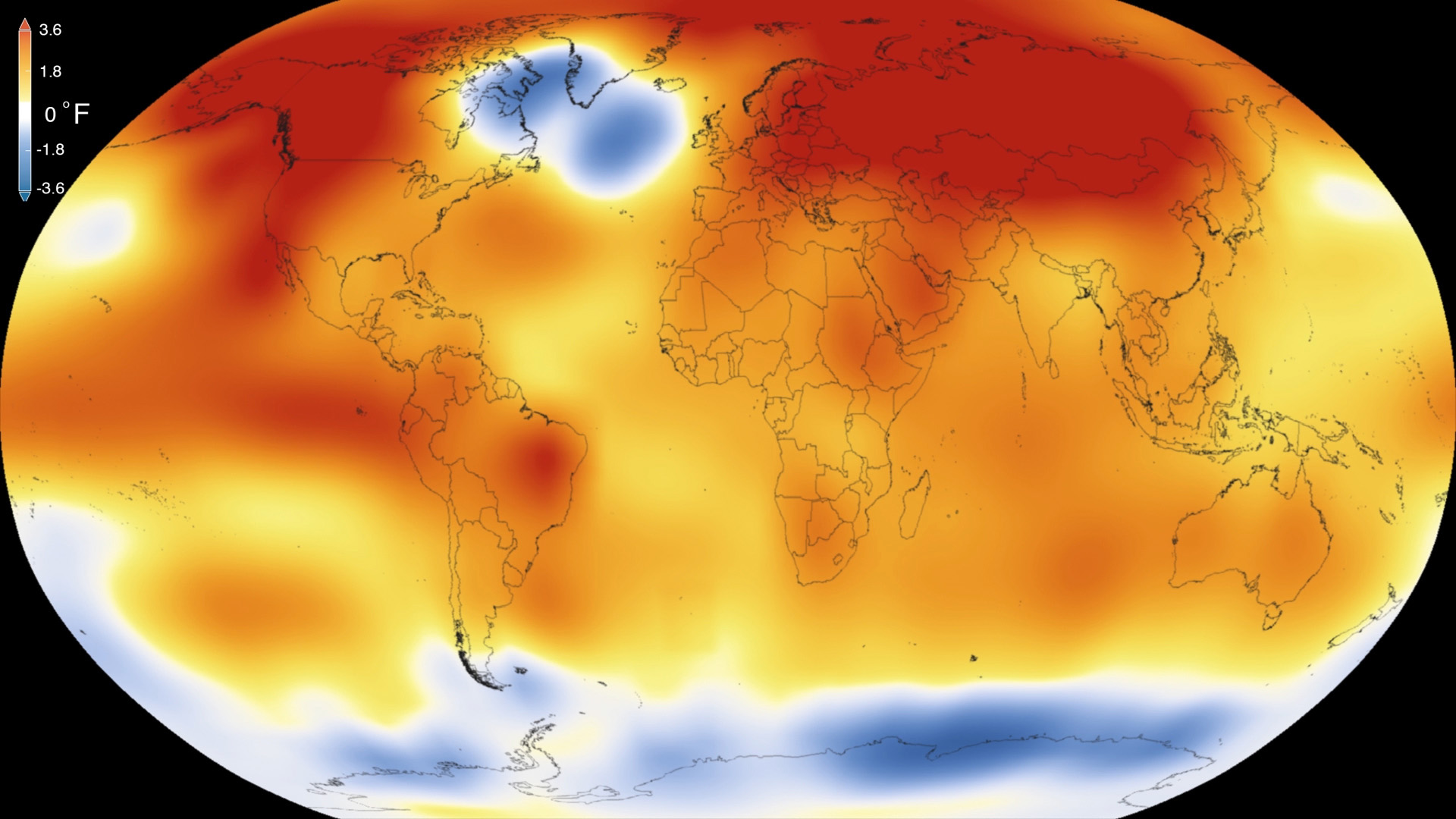

Map showing the latest trends in global warming: Scientific Visualization Studio/Goddard Space Flight Center

By Glynn Wilson –

A significant group of climate scientists issued a dramatic editorial statement in the journal Nature Climate Change this week on the effects of human induced global warming from the burning of fossil fuels. They make the argument that we are making a mistake to only think about the effects of global warming over the next century, when all the data points to impacts of carbon pollution over the next 10,000 years.

“The next few decades offer a brief window of opportunity to minimize large-scale and potentially catastrophic climate change that will extend longer than the entire history of human civilization thus far,” the statement says.

Peter Clark from Oregon State University is listed as the lead author along with 22 other scientists who study climate. The authors include a number of influential climate scientists and key leaders behind major reports from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, including MIT’s Susan Solomon and Thomas Stocker of the University of Bern in Switzerland.

“There is scientific consensus that unmitigated carbon emissions will lead to global warming of at least several degrees Celsius by 2100, resulting in high-impact local, regional and global risks to human society and natural ecosystems,” they say. “Despite this consensus, international efforts to address the challenge of global climate change have been and remain limited in scope. We suggest that one important factor contributing to this impasse is the focus of the scientific community on near-term climate changes and their uncertainties. In particular, the scientific emphasis on the expected climate changes by 2100, which was originally driven by past computational capabilities, has created a misleading impression in the public arena — the impression that human-caused climate change is a twenty-first-century problem, and that post-2100 changes are of secondary importance, or may be reversed with emissions reductions at that time.”

A key point of the new study it to show that carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for a long time before dissipating slowly by natural processes.

“A considerable fraction of the carbon emitted to date and in the next 100 years will remain in the atmosphere for tens to hundreds of thousands of years,” the study noted.

Meanwhile, the planet’s sea levels adjust gradually to its rising temperature over thousands of years.

“In hundreds of years from now, people will look back and say, ‘yeah, the sea level is rising, it will continue to rise, we live with a constant rise of sea level because of these people 200 years ago that used coal, and oil, and gas,’ ” said Anders Levermann, a sea-level-rise expert at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and one of the paper’s authors. “If you just look at this, it’s stunning that we can make such a long-lasting impact that has the same magnitude as the ice ages.”

So what will the world look like in 10,000 years, thanks to humans? That really depends on what we do in the next few hundred years with the fossil fuels to which we have relatively easy access. It also depends on whether or not we develop technologies that are capable of pulling carbon dioxide out of the air on a massive scale, comparable to the amount that we’re currently emitting.

Video: Watching rising sea levels from space

Oceanographer Josh Willis from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory explains how sea levels have changed over the last two decades. (NASA)

The editorial statement on the front of the journal is “a statement of worry,” said Raymond Pierrehumbert, a geoscientist at Oxford University and one of the study’s authors. “And actually, most of us who have worked both on paleoclimate and the future have been terrified by the idea of doubling or quadrupling CO2 right from the get-go.”

Assuming people don’t develop such mitigation technologies, here are the key factors to consider about how we are shaping the planet’s very distant future.

From 1750 to the present, human activities put about 580 billion metric tons, or gigatons, of carbon into the atmosphere — which converts into more than 2,000 gigatons of carbon dioxide (which has a larger molecular weight).

We’re currently emitting about 10 gigatons of carbon per year — a number that is still expected to rise further in the future. The study therefore considers whether we will emit somewhere around another 700 gigatons in this century (which, with 70 years at 10 gigatons per year, could happen easily), reaching a total cumulative emissions of 1,280 gigatons — or whether we will go much further than that, reaching total cumulative levels as high as 5,120 gigatons. (It also considered scenarios in between.)

In 10,000 years, if we totally drill, baby, drill, the planet could ultimately be an astonishing 7 degrees Celsius warmer on average and feature seas 52 meters (170 feet) higher than they are now, the paper suggests. There would be almost no mountain glaciers left in temperate latitudes, Greenland would give up all of its ice and Antarctica would give up almost 45 meters worth of sea level rise, the study suggests.

Anyone observing the world’s recent mobilization to address climate change in Paris in late 2015 would reasonably question whether humanity will indeed emit this much carbon. With the efforts now afoot to constrain emissions and develop clean energy worldwide, it stands to reason that we won’t go so far.

“With Paris, it does get us off the exponential growth, and we might level off at 2,000, 3,000 gigatons,” Pierrehumbert says.

What is striking is that when the paper outlines a much more modest 1,280-gigaton scenario — one that does not seem unreasonable, and that would only push the globe a little bit of the way beyond a rise of 2 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial temperature levels — the impacts over 10,000 years are still projected to be fairly dramatic.

In this scenario, we only lose 70 percent of glaciers outside of Greenland and Antarctica. Greenland gives up as much as four meters of sea level rise (out of a potential seven), while Antarctica could give up up to 24. Combined with thermal expansion of the oceans, this scenario could mean seas rise an estimated 25 meters (or 82 feet) higher in 10,000 years.

A key factor that could mitigate this dire forecast is the potential development of technologies that could remove carbon dioxide from the air and thus cool down the planet much faster than the Earth on its own can through natural processes.

“If we want to have some backstop technology to avoid this, we really ought to be putting a lot more money into carbon dioxide removal,” Pierrehumbert told a reporter for the Washington Post.

Pierrehumbert said he believes that we will manage to develop such a technology in coming centuries, so long as human societies remain wealthy enough — but he added that we don’t know yet about how affordable it will be.

The new study fits into a growing body of scientific analysis suggesting that human alteration of the planet has truly brought on a new geological epoch, which has been dubbed the “anthropocene.” Taking a 10,000-year perspective certainly reinforces the geological scale of what’s currently happening.

The ability to carry an analysis out so far into the future, Levermann said, is really the result in recent years of several key scientific developments. One is that “we are now in a better position to model the ice sheets, really,” he said.

Scientists have also recently begun to calculate so-called carbon budgets that describe how much we can emit and still hold the planet to a variety of temperature thresholds.

All of this coming together means that a conversation about increasingly long-range forecasts, and about the millennial scale consequences of today’s greenhouse gas emissions, is growing within the scientific world.

The question remains whether a similar conversation will finally take hold in the political realm and reach the mass public in time.

le changement climatique sera de pire en pire dans dix ans aura plus rien si personnes bouges ses pas trop tard si tout monde faisait des effort faut diminuer le combustibles co2