Will the City Government Side With the People or Industry?

By Glynn Wilson –

MOBILE, Ala. — The citizens of Mobile, especially those in the historic Africatown community along with members of the Mobile Bay Sierra Club, have held public meetings and spoken up: They do not want the Mobile Planning Commission and the City Council to approve two giant petrochemical storage tank farms on the riverfront to house millions of gallons of oil, much of it the dirty Canadian tar sands crude activists are still fighting out west.

While activists are still engaged in the battle against the Keystone XL pipeline in places like Nebraska and Texas, the Canadian National Railroad is already bringing in the same thick, hot tar sands crude by rail, with plans to significantly increase the volume if larger storage facilities are approved by the local government.

The Planning Commission will hold a public hearing on Jan. 29 to take up the question, and members of the Africatown community are expected to show up in numbers to oppose it, along with members of the Sierra Club and other environmental activists from around the area.

The Mobile Bay Sierra Club hosted an educational public meeting focused on the tank farms at its January meeting at the Five Rivers Delta Resource Center on the old Mobile Bay causeway.

Watch the Video

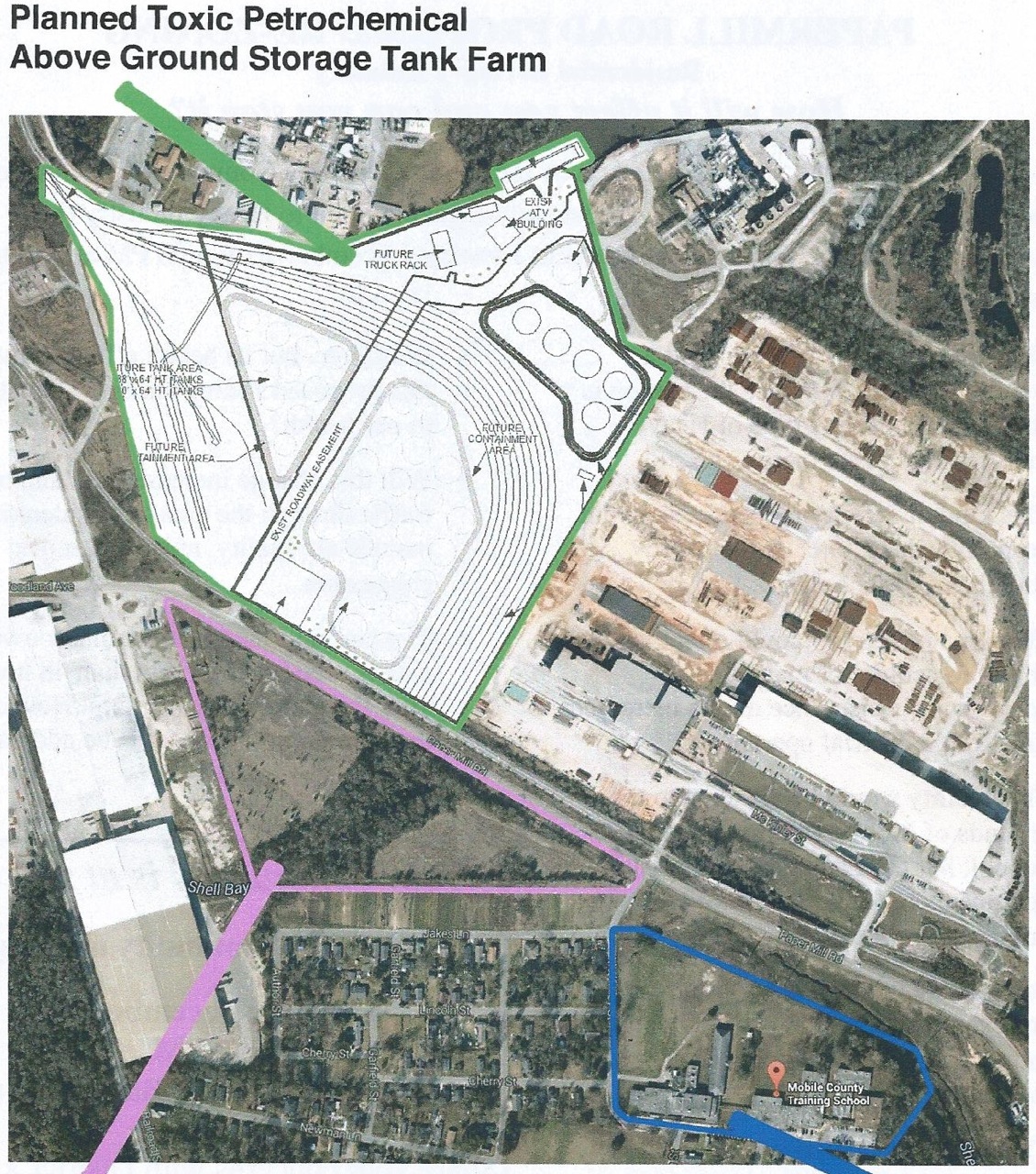

Then in a recent public meeting about the future of Africatown, City Councilman Levon Manzie, who also sits on the Planning Commission, solicited citizen comments on alternative investments in capital improvements from new city sales tax revenue as an alternative to more polluting industries, especially a proposed new tar sands oil tank farm on the old International Paper site on Hog Bayou.

At the Sierra meeting, retired engineer John Anderson made a presentation of the facts about the plans, risks and potential benefits of such a dramatic increase in the volume of some of the world’s dirtiest, most climate changing oil in a coastal metro area of nearly a half a million people who have already suffered from disasters such as the BP Oil Spill and hurricanes Ivan and Katrina.

“We’re at the end of the line between Alberta, Canada and Mobile, Alabama for the CN Railroad,” Anderson said. “That’s why we’re the target.”

In addition to the millions of gallons of petrochemicals already flooding through Mobile, the new plan to feed the Chevron refinery in Pascagoula, Mississippi involves 120 rail cars a day coming into the city carrying roughly 83,000 barrels.

It’s so easy to get a pollution permit in Alabama that Arc Terminals already has its water discharge permit, Anderson said, without any state, federal or local requirement that companies practice vapor recovery for their toxic releases of Volatile Organic Compounds — a routine requirement in many other states with the cost easily absorbed by the companies. The releases contain a toxic stew of cancerous chemical compounds, and they make their way into the water and the air.

“This is really great stuff for us to be breathing, our children and the people who live here,” Anderson said sardonically.

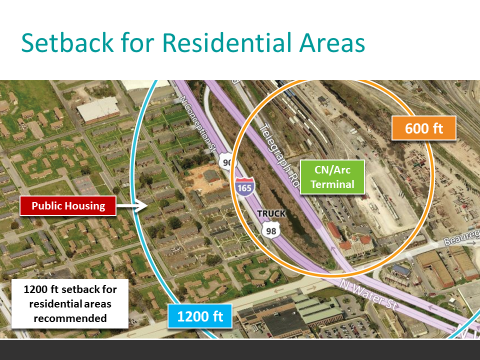

Nor are the companies required to conform to setbacks from populated areas, where in addition to setbacks, protective blast walls are required in states such as California. The Arc plant is set to be unloading thick, heated oil right on the other side of a rickety wooden fence behind Mobile’s main metro bus transfer station, where hundreds of travelers pass each day on their way to work or to Atlanta and other points around the region.

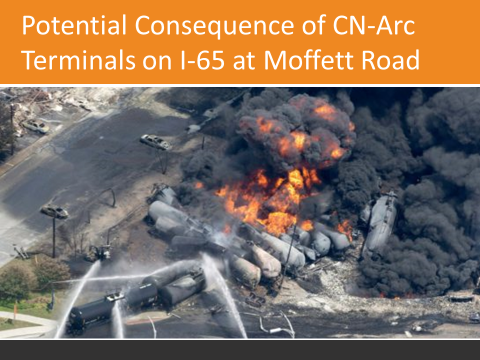

“You can imagine the potential for an explosion, a catastrophic event,” Anderson said.

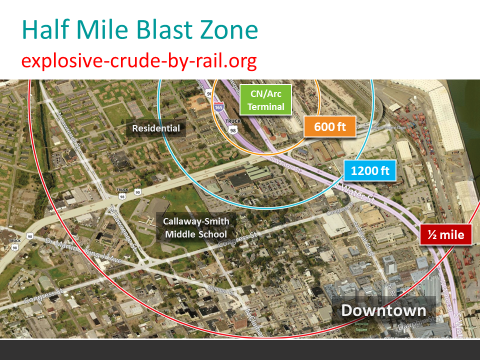

And while federal guidelines recommend a minimum of 1200 feet from residences, in the absence of a local setback ordinance, in this case it will be as close as 600 feet.

“If you look at where it is in terms of residential, in terms of people gathering, it’s a terrible place to put a facility,” Anderson said.

Some of the rail cars will also be transporting Bakken crude containing natural gas, diesel fuel, even heating oil. To the outsider it’s impossible to know which rail cars or tanks carry what mixture of crude. Dating back to the Bush-Cheney era, industry is not required to disclose it and the meaning of the numerical code posted on the cars and tanks is considered a closely held business secret.

“It’s a highly flammable material,” Anderson said. “The same kind that blew up (in Quebec), killing 47 people.”

The United States has major problems with its outdated rail system, where most of the cars are 40 to 50 years old designed to carry oil, but not the heated up combinations being proposed and shipped here now. Another problem is that Berkshire Hathaway owns about 40 percent of the rail cars in the U.S., and without any mandates from any government, the companies are not willing to invest in improvements. The Canadian government has required new cars in its territory.

“You think they want to spend millions and millions of dollars it would take to retrofit all those rail cars or replace them? Not in this lifetime,” Anderson said. The National Transportation Safety Board has encouraged it, he said, but the Obama administration has issued no such requirement.

“It’s basically not going to happen,” Anderson said. “All the new production will go to Canada and we’ll get all the old cars in the United States.”

Right now Arc has enough storage tanks to house about 2 million barrels across the river from downtown, but they are planning to double that to 4 million barrels. Then there’s the other company planning to open another 2 million barrel storage plant on the old vacant International Paper property in Africatown.

Those pipelines will all connect to the new Plains Southcap pipeline going under the city’s drinking water supply at Big Creek Lake on the way to Pascagoula.

“We’ll end up with probably about 6 or 8 million (barrels) of storage in our neighborhood,” Anderson said.

The Arc site alone will require two new pipelines under the Mobile River. It is not hard to imagine a number of potentially catastrophic scenarios, Anderson said, from a truck and train wreck to a violent storm to a terrorist attack.

“You could have a major catastrophe here in downtown Mobile,” he said.

To see if you are in the blast zone, you can check explosivecrudebyrail.org online and type in your address.

“Think about three and a half million gallons of natural gas in Big Creek Lake,” Anderson said. “We’d all be looking for something to drink. What’s coming out of your faucet would be on fire.”

The vapors from the diluted bitumen in the trains and tanks will lead to an increase in Mobile’s ozone levels that are already hovering just one 100th of a point below the EPA’s safe attainment level of 0.075 parts per million. VOC pollution contains benzene, a known human carcinogen that also causes birth defects, leukemia, anemia and other blood disorders, especially in the young and old.

“If diluted bitumen starts being unloaded in Mobile, I really believe we’re going to exceed the threshold value (and be declared in non-attainment),” he said.

The only benefits Anderson could surmise from the project would be 12 to 25 local jobs along with a one time engineering contract and a one time construction contract. While increasing profits for the Canadian tar sands crude producers, the Canadian National Railroad and Arc, it would reduce shipping costs for the Chevron refinery and increase cargo shipping through the State Docks. But while the company receives major tax credits for building the plant, the local tax revenue that could come back to Mobile is minimal.

The risks include the potential for a major derailment and explosion, contamination of the drinking water supply, increased health and safety threats to the local citizens from reduced air quality, and even a catastrophic oil spill during a major storm surge from a hurricane. Then there is the additional contribution to the global threat of climate change from the burning of fossil fuels both here and abroad.

Anderson recommended staying in touch with local officials with the Planning Commission, the City Council, and pushing for local ordinances for capturing VOCs, establishing setbacks from churches, homes and public gathering places, and tighter controls on storage tanks.

“If you have enough ordinances and require them to spend enough money, some of these companies will go somewhere else,” Anderson said. “Basically the only thing that protects the people in the community is the zoning enacted by the people we elect.”

The situation is dire but not hopeless, Anderson said. He reminded folks of the fights in the 1970s and ‘80s over oil companies dumping drilling waste into the bay and coastal waters. I broke the story on that in the 1980s for Gulf Coast Newspapers and UPI, and there is a chapter in my upcoming book explaining the role of the free press in helping to make democracy work.

“The people in this community said we don’t want the drill mud in the bottom of the bay,” Anderson said. So oil companies had to figure out how to capture it and barge it to hazardous waste landfills.

“That procedure is now a worldwide standard,” Anderson said. “It started right here on Mobile Bay. We do have the power. If we just have the political will. It’s takes everybody in this room and a bunch of other people to make that happen.”

Joe Womack of Africatown took some heart from Anderson’s words, and took them back to the people of his community, who are planning to show up for the Planning Commission meeting on Thursday.

In an e-mail blast to the people in the neighborhood, he urged them to attend and get there early, since the proposed tar sands oil tank farm across the street from a historic school places the community and its residents, schools and churches “within the kill zone of an explosion.”

Councilman Levon Manzie led a community meeting with more than 100 residents in attendance, largely focused on how to spend Africatown’s share of $3 million to be allocated to each of the 7 council districts in the city from the sales tax. The Africatown Community Development Corporation handed out information recommending the purchase of vacant land under constant assault from industry.

Womack said Hog Bayou is part of Alabama’s Tensaw River Delta and the only potential entrance that could be utilized from the city — if it was protected along with the rest of the Delta and used for public access or even an entertainment district by Mobile — rather than further damaging the area with a new oil tank farm.

Councilman Manzie mentioned the recent victory of the community by putting on the pressure to stop a steel warehouse rezoning in the area, and urged everyone to attend the Jan. 29 Planning Commission meeting.

“Come early,” he said. “The Planning Commission and members of the City Council need to hear from as many residents as possible that ‘we do not want these oil storage tanks proliferating throughout our community’.”

Watch the Video

More Graphics and Photos

Standing with you in this effort. Joining the Voice.

Can this information be shared with the public on Earth Day in Fairhope? Also, I think the newspapers should publish the information which Dr. Eichold stated at the meeting with the City of Mobile Planning Commission. I hope that the citizens of Mobile and Baldwin counties who oppose the storage tanks and/or the Pipeline will continue to express their concerns in order to preserve and protect Mobile, and the Gulf of Mexico.

Sure. Share far and wide.

Good luck with the news “papers.” They are not exactly covering this.