“Sometimes you eat the bear, and sometimes the bear eats you.”

– Sam Elliott as The Stranger in “The Big Lebowski.”

Tales From the MoJo Road –

By Glynn Wilson –

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, Calif. – Sometimes in this crazy, mixed up world, the written word can make all the difference.

Yet sometimes, no matter how hard you try, the written facts are not enough.

Sometimes when you are on the road you miss the story entirely.

And sometimes when you find yourself in the heat of a major battle, no matter how hard you try, you find yourself on the losing side.

Such is life.

“Sometimes you eat the bear, and sometimes the bear eats you.”

Before there was a Sam Elliott or Jeffrey “The Dude” Lebowski, there was a writer and influential transcendentalist thinker named Ralph Waldo Emerson. In an essay on “Farming” published in an 1870 collection of stories, Emerson described a beleaguered primal human figure, whose diet included foods derived from plants and animals. Hunting megafauna like bear was a dangerous endeavor, he wrote.

“He is a poor creature; he scratches with a sharp stick, lives in a cave or a hutch, has no road but the trail of the moose or bear; he lives on their flesh when he can kill one, on roots and fruits when he cannot. He falls, and is lame; he coughs, he has a stitch in his side, he has a fever and chills: when he is hungry,” Emerson wrote, “he cannot always kill and eat a bear … sometimes the bear eats him.”

Back in his day, John Muir knew the thrill of victory, and the agony of defeat.

And so it is in our life and times as well.

Muir succeeded in talking President Teddy Roosevelt into expanding national protections for forests and creating more national parks. But in his final battle trying to prevent a dam in Hetch Hetchy Valley in the northwestern part of Yosemite National Park on the Tuolumne River, he lost. The lake that was created by the dam is still a water reservoir for the city of San Francisco.

I’ve fought and helped win a number of battles in favor of democracy over authoritarianism, and for the natural environment over commercialized development. Many of them are documented in my memoir, Jump On The Bus: Make Democracy Work Again.

Here’s one example. Working with the Sierra Club, started by John Muir, my journalism was critical in stopping fracking in the Talladega National Forest. It was the only case of its kind in the country at the time.

Fracking in the Talladega National Forest is Not in the National, State or Local Interest

But I’ve lost some too. In the same place, we lost the battle to save the Chinnabee Campground when the U.S. Forest Service rangers in the state decided it was dangerous and closed it. It would have been in the center of the map for Halliburton’s plan to frack for natural gas. A minor spring flood of the access road by the small boat launch should not have been grounds for closing it permanently.

They did it out of spite after charging me with entering a closed federal area, with a ticket for $125 – a charge I beat in federal court.

I ate the bear that day, and bought the drinks on Southside.

The Battle for Yosemite Names

A few years ago, I wrote about a battle between the National Park Service and private concessionaire Delaware North over the intellectual property in Yosemite National Park.

U.S. Park Service Escalates Battle Over Yosemite Trademark Names With Delaware North

But on the road in the summer of 2019, I missed the story on a legal settlement in that case. I only learned about it recently from a Facebook post on the Yosemite National Park Facebook group.

Sometimes the bear eats you.

Background

First a little background. This goes to the heart of the ongoing struggle to prevent the National Parks from being totally privatized and commercialized.

The mob company Delaware North started with dog tracks in Arkansas, then branched out into running hotels, restaurants and catering services, including the inaugural parties of President Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. By making large campaign contributions, it weaseled its way into contracts with the national parks.

Delaware North became the provider of visitor services at Yosemite National Park first in 1993 under contract with the National Park Service, via the subsidiary DNC Parks and Resorts at Yosemite, Inc. It was a political payoff.

When the contract was canceled due to disgruntlement with its services, and acquired by another concessionaire company, Aramark, in 2015, that company was required to purchase the assets of the previous concessionaire: Delaware North. But that company claimed that the sale did not include its intellectual property, which it claimed included trademarks for many of the historic place names in the park, including the historic Ahwahnee Hotel, Badger Pass, Curry Village, Yosemite Lodge, and the slogan “Go climb a rock.” The private company claimed this was valued at $51 million. Delaware North sued the United States in the Court of Federal Claims in 2015. The NPS disputed the cost of these intangible assets, as well as Delaware North having registered the names in the first place.

In January 2016, it was announced that due to the legal dispute, properties at Yosemite National Park would be renamed effective March 1, 2016, when Aramark’s contract officially began. The Ahwahnee was renamed the Majestic Yosemite Hotel, Camp Curry was renamed Half Dome Village, the Yosemite Lodge became Yosemite Valley Lodge, the Wawona Hotel became Big Tree Lodge, and the Badger Pass Ski Area became the Yosemite Ski & Snowboard Area. Upon Aramark’s transition to concessionaire in March 2016, the trademarked place names were replaced by the alternative names and new signs had to be made.

In July 2019, the National Park Service finally reached a settlement agreement with Delaware North for roughly $12 million, including an agreement to return the trademarks to the NPS upon the conclusion of Aramark’s contract, when the original place names were restored.

Sometimes you eat the bear, after paying dearly for the meal.

Yosemite National Park trademarks dispute

The Incomparable Yosemite

When John Muir first found Yosemite, he described it as “The Incomparable Yosemite.”

The most famous and accessible of these cañon valleys, and also the one

that presents their most striking and sublime features on the grandest

scale, is the Yosemite, situated in the basin of the Merced River at an

elevation of 4000 feet above the level of the sea. It is about seven

miles long, half a mile to a mile wide, and nearly a mile deep in the

solid granite flank of the range. The walls are made up of rocks,

mountains in size, partly separated from each other by side cañons, and

they are so sheer in front, and so compactly and harmoniously arranged

on a level floor, that the Valley, comprehensively seen, looks like an

immense hall or temple lighted from above.But no temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite. Every rock in

its walls seems to glow with life. …The Approach To The Valley

Sauntering up the foothills to Yosemite by any of the old trails or

roads in use before the railway was built from the town of Merced up

the river to the boundary of Yosemite Park, richer and wilder become

the forests and streams. At an elevation of 6000 feet above the level

of the sea the silver firs are 200 feet high, with branches whorled

around the colossal shafts in regular order, and every branch

beautifully pinnate like a fern frond. The Douglas spruce, the yellow

and sugar pines and brown-barked Libocedrus here reach their finest

developments of beauty and grandeur. The majestic Sequoia is here, too,

the king of conifers, the noblest of all the noble race. …

The Yosemite Fall

“So grandly does this magnificent fall display itself from the floor of the Valley, few visitors take the trouble to climb the walls to gain nearer views, unable to realize how vastly more impressive it is near by than at a distance of one or two miles.”

– John Muir

Hetch Hetchy Dam

“These temple-destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the mountains, lift them to the Almighty Dollar. Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.”

– John Muir, The Yosemite (1912) chapter 15.

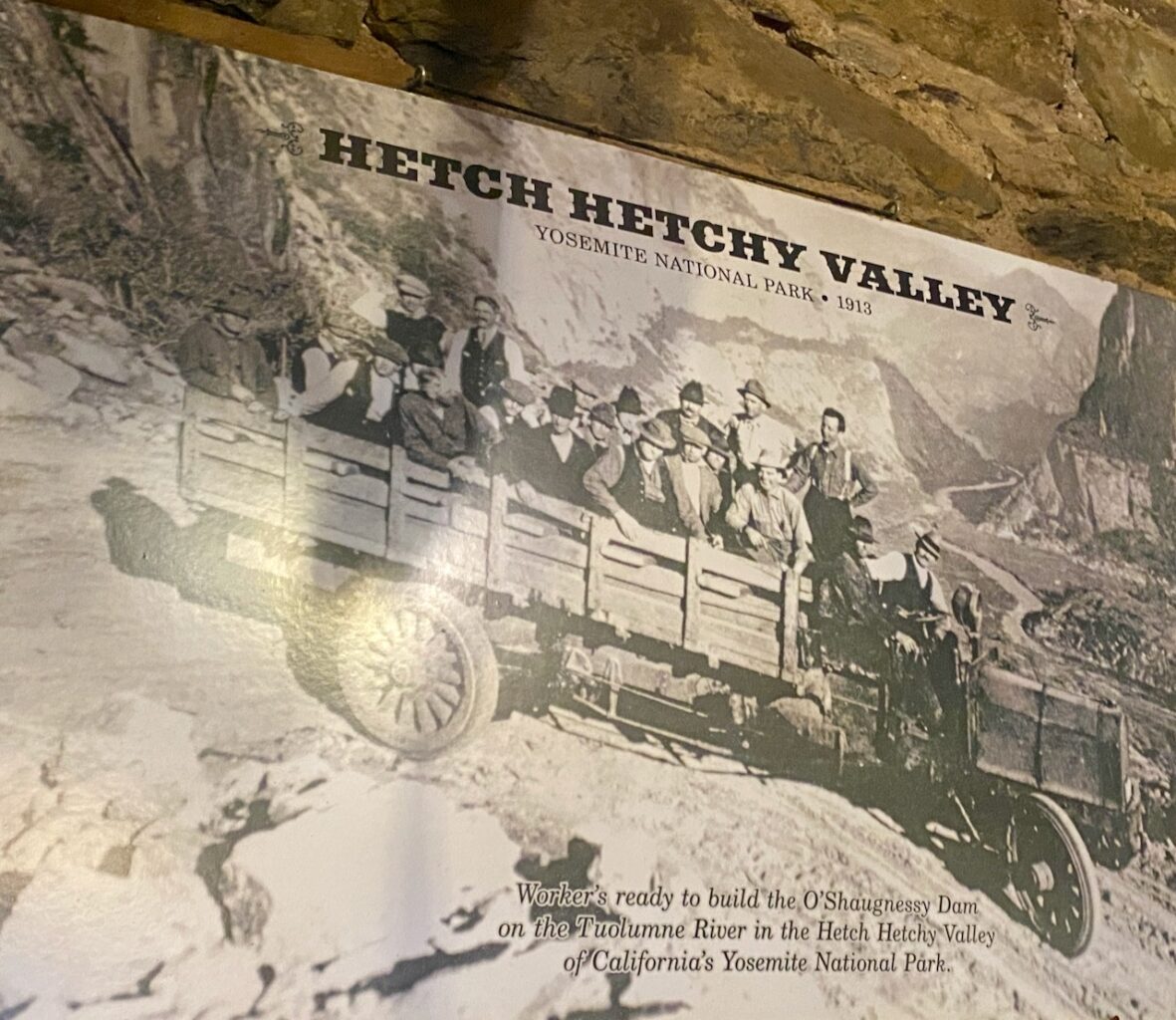

This picture of men working on the Hetch Hetchy dam hangs in the Iron Door Saloon in Groveland: By Glynn Wilson

With population growth continuing in San Francisco, political pressure increased to dam the Tuolumne River for use as a water reservoir. Muir passionately opposed the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley because he found it about as stunning as Yosemite Valley. Muir, the Sierra Club and Robert Underwood Johnson fought against inundating the valley. Muir wrote to President Teddy Roosevelt pleading for him to scuttle the project. Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, suspended the Interior Department’s approval for the Hetch Hetchy right-of-way. After years of national debate, Taft’s successor Woodrow Wilson signed the bill authorizing the dam into law on December 19, 1913.

Muir felt a great loss from the destruction of the valley, his last major battle. He wrote to his friend Vernon Kellogg, “As to the loss of the Sierra Park Valley [Hetch Hetchy] it’s hard to bear. The destruction of the charming groves and gardens, the finest in all California, goes to my heart.”

Sometimes the bear eats you.

When a battle has to be fought, an organization will usually have to be brought together to fight it, and one man will cast a shadow, or otherwise exert a profound influence, over the organization. To date, John Muir’s shadow is seventy-three years long in the kind of battle Americans will need to fight recurrently.

When Congress set Yosemite Valley aside in 1864 as a park for the nation, a contest began between those who sought to preserve it for all and those who sought commercial advantage in it for themselves. Central to this contest were a man and an organization – John Muir and the Sierra Club he helped found in 1892, two years after the establishment of Yosemite National Park and its two million acres of High Sierra surrounding Yosemite Valley.

Some of the battles were won: the first attempt at a major cut back of the boundaries was staved off and the unification of Valley and Park under federal control was achieved. But the greatest battle was lost: Hetch Hetchy Valley, second only to Yosemite Valley itself, was dammed and flooded to supply power and water for San Francisco, even though a federal advisory board of Army Engineers had said that other sources were available, “sufficient in quantity,…. suitable in quality,” their engineering problems “not insurmountable”; the determining factor was “principally one of cost.”

What was the price of this particular scenic heritage for Americans? This was the question Muir and the Club tried to find an answer for, and in the years that followed, the Club was to continue to seek answers to the same question for other beautiful and threatened places. In Hetch Hetchy Muir and the club failed to persuade an administration committed to commodity use; the rift between the preservationists and the utilitarian resource managers was made clear.

The Sierra Club was established specifically to rally citizens who believed in the preservation of the High Sierra and who understood the need for eternal vigilance in its protection. The Club’s vigorous beginnings with Muir and a devoted group of Bay Area professors and businessmen have been strengthened through the years by people in all walks of life all over the United States who believe that dynamic action will preserve some areas of superlative beauty.

Parts of this story of the background of the Sierra Club, of the accounts of the first stirring of the nation’s conservation conscience, read like some current paragraphs of the Congressional Record or the transcript of hearings on the damming of the Colorado River or the adequacy of the proposed boundaries for a redwood national park. The arguments for and against preservation are still the same; they have been heard and are heard over many years and in many places – in Dinosaur National Monument, on the Hudson and the Potomac, on the Olympic Strip, and along the Colorado River. The chief argument for preservation is that one generation cannot responsibly commit future generations to a world deprived of wildness, to a managed world where nature is to be observed only in plots, like specimen wild creatures in zoos. The chief argument for commercial development too often, is that it saves money. Alternatives which spare natural beauty will usually have a higher initial cost, but an affluent society, a Great Society, should be willing to pay it, for there is a perpetual return from the investment!

But the climate for these battles is not quite the same as it was when the Sierra Club began. The nation’s once dimly aroused conservation conscience is now becoming more insistent as the acceleration of change makes inescapable an awareness of cause of change – man’s overenamour of technology and reckless growth. Part of this new and more favorable climate for conservation is a heritage from Muir and his colleagues, whose foresight created the Sierra Club and whose commons sense kept it tough and viable. This is their story – the first chapter in a fight that has filled several chapters since then and will probably never quite end.

NPS – The History of Hetch Hetchy Valley: A Detailed Timeline

John Muir died on Dec. 24, 1914 of pneumonia at the age of 76.

HETCH HETCHY: The Epic Environmental Battle That Changed America

There is a new movement to restore Hetch Hetchy “for a second Yosemite.”

Perhaps I will join the battle.

Who would like to eat that bear?

GCW

More Photos

It wasn’t a great day for light, with dark clouds and high overcast. We got a few decent shots for documentation and learned more about the place. We will be back for more.

Great photos and interesting chronicle of history.