By Edgar Wilson –

America has another chance to learn from developing regions threatened by a dangerous virus.

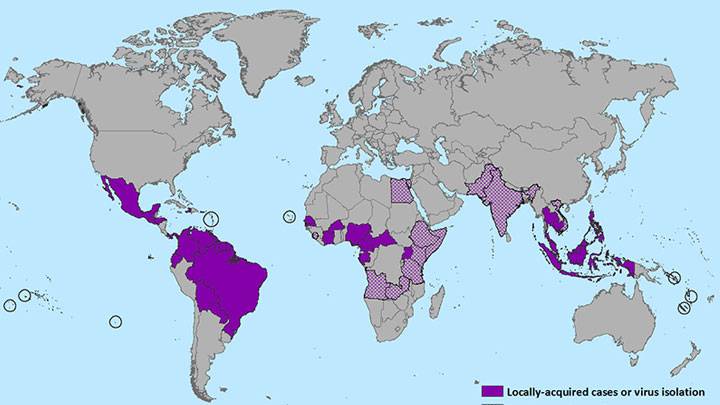

The mosquito-borne Zika virus, normally found across central Africa and Southeast Asia, has been turning up in more and more countries throughout the Americas, with its biggest footprint in Brazil.

In roughly three-quarters of all cases, Zika infections present no symptoms, while the remaining quarter usually present typical flu-like complaints; far from making the virus innocuous, however, this symptom-free infection is what makes it so incredibly troubling. Zika has been pretty firmly (though not definitively) linked to a sudden surge in microcephaly (underdeveloped heads and brains) among newborns in the worst-afflicted countries, with Brazil so far recording it at more than 20 times the normal rate.

Because Zika is not generally communicable—unlike 2014’s Ebola outbreak, which necessitated extensive containment and decontamination measures—intervention strategies are complicated, and limited opportunity for studying the virus means there is no cure or immunization. That is why, out of desperation, affected countries have begun recommending that citizens postpone getting pregnant until measures can be taken to better defend against infection.

El Salvador’s suggestion that its citizens postpone pregnancy for two full years has been met with spectacular outrage. In general, that righteous fury is woefully misplaced.

Critics have been quick to jump on this as evidence of population control efforts, an attack on personal liberty, and other such Big Brother alarmism. But this is far from an official edict: neither the citizenry nor the government has any real capacity to enforce something like this. As a hyper-violent, gang-addled, 50% Catholic nation, abortion is strictly illegal in El Salvador and access to contraceptives or even basic reproductive education services are extremely limited.

The greater lesson to be learned is how public infrastructure, mental health, and contraceptive services are all profoundly connected.

On the global level, it is unreasonable to believe that any public health problem can or will remain localized for long. While a very limited number Zika cases have been identified in the U.S. so far, experts believe it is only a matter of time before it and other tropical diseases become more common.

To be clear, “a matter of time” doesn’t just mean this year. Over the longer term, the forces of climate change are reshaping the migratory habits, behavior, and habitat distributions of many species (including mosquitoes), making it more difficult to predict how and when new disease might be carried into previously insulated parts of the world.

Fighting Zika means fighting mosquitos: that requires sanitation and maintenance infrastructure sufficient to minimize standing water (where mosquitos breed) as much as possible. In the worst-hit nations, this infrastructure and governmental organization was already lacking, and is now stretched to remediate the problem. That is why asking its people to limit sexual activity (Zika may be transmissible through intercourse, aside from causing birth deformities) has been a desperate back-up plan.

But behavior modification relies on a similar infrastructure and social organization—one that enables women to make their own reproductive and personal health choices, and gives them the educational and physical resources to do so.

The U.S. is still mired in controversy over the notion that reproductive health—women’s health, really—deserves to be universally covered. If Zika teaches us anything, it ought to be that population health cannot be separated from women’s reproductive rights, and that a health national infrastructure doesn’t just connect people to the internet or keep roads paved; it ensures everyone has access to basic healthcare resources, of which contraceptives are clearly an important part.

This misguided debate should have been put to rest long ago; righteous indignation at the responses of other countries can’t hide the fact that the U.S. still hasn’t reconciled the reality of women’s health needs with the politics of control.

Old biases and misconceptions are not limited to sexual politics.

In at least one respect—the survival rate—the global response to the Ebola outbreak was a success: more people were able to come away from infection with the virus without losing their lives. The aftermath is a somewhat different story. The mental and emotional trauma of facing death, forced isolation, and physical wounds resulting from Ebola continue to resonate among survivors.

The emotional neglect of Ebola survivors (and even those suspected of infection) contributed to prolonging the outbreak, because the fear of ostracism and loss of community drove people to hide symptoms and lie about exposure.

Even if Zika were contained and eliminated tomorrow, its impact would already be devastating not just in lives lost, but in the emotional trauma it has caused.

With thousands of expectant mothers coping with stillborn infants, or children so malformed they die soon after birth—to say nothing of those children healthy enough to live but doomed to a lifetime of difficulty and suffering and heightened dependence—the Zika outbreak is yet another wake-up call to the world to prioritize mental health right alongside physical health.

Knowing that emotional needs matter as much as hygiene in containing an outbreak might encourage people to be more proactive—but that requires a major shift in how healthcare is defined, managed, and provided.

Mental health professionals in the U.S. face many obstacles to achieving much-needed remediation, that would enable them to bring standards, access, and awareness to a basic level that better aligns emotional wellness in the greater continuum of care. When a country has a more robust baseline for integrating mental health in its approach to population health, it is better equipped to deal with extreme events like an outbreak.

The current conversation around Zika, as with Ebola, seems to be one of contrasting the U.S. with less-developed nations to downplay vulnerabilities. The opposite deserves to dominate discussion: the current Zika outbreak demonstrates how fundamental priorities need to change in the U.S., and how closely the problems of other nations are mirrored in this country.

Women’s rights, contraceptive access, mental health, and infrastructure development should all be beyond debate by this point, and instead be absolute priorities. They are just too deeply connected to the health and wellbeing of the entire planet.