By Glynn Wilson –

SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK, Va. — The Shenandoah salamander is no endangered polar bear, cuddly panda cub or playful dolphin the American public may warm up to in the cause of fighting global warming from the burning of fossil fuels. Yet it is the latest poster child from the National Park Service in the public battle for the nation’s attention to encourage them to help do something about climate change.

Congress seems incapable of acting even with the strong encouragement of the president of the United States and the CIA, which now considers climate change to be among the top security threats to the country. Knowing that it will take the involvement of the people to bring about political change to fight climate change, there is a constant debate inside the science community about how to get people educated and involved.

This is this one rare and endangered species that makes its only home on Earth in the high elevations of the Appalachian mountains in Virginia, and some visiting school children are warming up to it, rangers say.

If you’ve never climbed into these rugged peaks to hike, camp — or simply drive down Skyline Drive in Autumn when the leaves are changing colors — you are missing one of the best ideas which make America great. That is preserving forests as wildlife refuges and for the public to enjoy now and into the future.

You can’t bring your guns and shoot the black bears or white-tailed deer that live here in relative abundance. Pioneers from Europe killed off all the elk, wolves and bison that once made their home here along with the Native Americans who were run out. But you are welcome to try your hand at nature photography, even if it is only on with an iPhone from one of the many overlooks.

On a recent trip through the park and a stop at Big Meadows, the largest campground with the most amenities in Shenandoah, we encountered Sally Hurlbert, a tall drink of a ranger who conducts interpretive talks for tourists, along with the occasional Web Journalist sporting a video camera. She was gracious enough to take the time to do a video interview with me to talk about the potential effects of climate change on the park.

While the public may know about the shrinking glaciers in places like Glacier National Park in Montana, or rising sea levels beginning to have an effect on the Gulf Coast and places such as the Everglades, they may not be as familiar with the idea that global warming caused climate change can lead to more severe draughts and fires as well as storms and floods in places like the Appalachians.

“With the changing climate and temperatures warming, we are worried about what the impact is going to be on our wildlife,” Ranger Hurlbert said. “Not just animals, but plants as well.”

Shenandoah Salamander, Plethodon shenandoah amphibian; Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, Appalachian Mountains: NPS

One species now under study that lives only on North facing talus slopes on three mountain tops inside the park is the Shenandoah salamander [plethodon shenandoah], facing a threat to its existence not only from its extremely restricted range, but from defoliation of trees by gypsy moths, competition with redbacked salamanders, the deadly amphibian pathogen batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, as well as climate change.

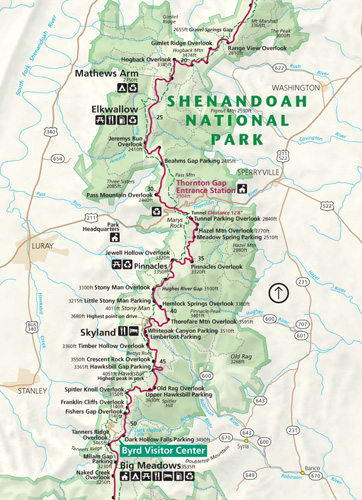

“It lives underground, especially in the summertime, so it’s pretty reclusive,” said Chief Interpretive Ranger Jim Schuberl, who we caught up with at the base of the mountain at park headquarters in Luray Virginia.

“It’s hard to determine what it really needs, and what the threats are from (a changing) climate,” he said. “But everything, all the models, all the data, all the science for a number of years now point to the fact that it’s least a 30 percent chance of extinction because, from what we can tell, the major reason would be climate change.”

That means increases in temperatures even at the high elevations and certainly more frequent and powerful storms, with the increase in precipitation that comes along with all that snow and rain.

We encountered and escaped out from under two of those storms on recent trips to and from Washington. We drove in rush hour traffic out of Takoma Park Maryland one morning as a Nor’easter blew down the East Coast form the north. By the time we passed Manassas Virginia to the west, however, the fog and rain cleared and we began a 12 day fall trip down Shenandoah way.

Then on the way back from Charlotsville on the way back, after a trip to Monticello, we ran from a menacing storm coming out of the west that looked like it was trying to form multiple tornadoes. A 60 mile an hour wind came over the Shenandoah mountains not only blowing off most of the remaining leaves on the trees for the year. It nearly blew cars, vans and trucks off the road coming over a couple of hills along Highway 29.

But blue skies and white clouds beckoned to the northeast, so we ducked into a private campground down in the next valley and found a quiet, uneventful spot in the universe to spend the night.

Why should people care about this lowly salamander living in the rocks way up in the mountains?

“Because it’s part of the eco-system, one part of the food chain,” Ranger Hurlbert said. “It depends on other species to survive and some depend on it as well. If we lose one part of the food chain, it affects all the other parts of the food chain.”

In addition to heat, storms and rain, the changing climate is paving the way, so to speak, for invasive species which tend to thrive in the warmer climate, such as the woolly adelgid now attacking the Hemlock trees in a big way.

“Right now, to the best of our knowledge, 95 percent of the Hemlocks that we had in the 1990s are gone,” Schuberl said. “We’ve got about 5 percent left, and that’s a result of treatment.”

They find the trees and implant root injections to ward off the pests, “one tree at a time,” he said. “Until we can figure out something more systematic like biocontrol. We’re trying to hang on to that remaining 5 percent, which is kind of sad.”

Perhaps one day the science will be there to save these things. But for now, the hope is to hang on to the genetic pool, the remnant hemlocks, so they don’t go the way of the Chestnut or the dodo bird.

A few minutes into the conversation, Ranger Schuberl opens up even more and talks about a whole series of “emerging threats” that are taxing scientific as well as economic resources to tackle. While just about everyone knows about the Chestnut blight, he says now there is a “huge, perturbation going on in this forest. This constant change because of something non-native.”

There’s the emerald ash borer beetle going after the Ash trees, accidentally brought to America in the ash wood used to stabilize crates for shipping from eastern Russia, northern China, Japan and Korea.

“There’s no known solution to that right now,” he said, although they have released thousands of Japanese ladybugs to go after the woolly adelgid, a period-sized bug that drains the sap from hemlock trees and kills them.

The gypsy moth, [lymantria dispar], has also been identified as a threat for years, although Schuberl said a fungus that kills them has come along to stabilize that population and slow its spread.

Feral hogs are also a growing threat in Shenandoah, as they have been for many years in the Great Smoky Mountains.

“It just seems like there’s one after the other, just in the past (few) years,” Schuberl said. “There’s all these invasive critters, in addition to all the invasive plants — probably doing better because of climate change.”

Most people probably know about kudzu, which is now on the edge of Shenandoah, Schuberl said.

Then there’s the mile-a-minute weed, he pointed out with its appropriate name, [persicaria perfoliata], also known as devil’s tail, just one of the many outside agitators the federal government spends time and resources trying to combat, especially in the sensitive high elevation communities.

At last count, there were 360 non native “fast killer species,” he said. “We can’t chase all of that. We have to focus on the most invasive, the most challenging. And do it surgically.”

“We can’t do it park wide. There’s just too much of it, and too many species,” he said. “It’s a constant reactive struggle. It’s a triage decision making process.”

Fire is becoming more of a threat in the East like is already is out West, Schuberl acknowledged.

But it’s not just about what’s going to happen in the future. It what’s already been measured for the past couple of decades.

“The climate, precipitation events, as we’re recording them, seem to be getting more extreme,” Schuberl said categorically. “It seems like we are often matching or exceeding records.”

The wettest spring followed by the driest fall, which also impact popular and economically important aquatic species such as brook trout and the other cold water animals in that environment. Records show temperature are rising in the mountain streams as well as the surface air temperatures and in the oceans.

So record rainfall in the spring followed by a severe drought in the fall could devastate the fishing in some of the nation’s top trout streams in addition to the cumulative environmental effects.

“The water temperature is going up,” Schuberl said. “It’s not one-to-one with the air temperatures, but it is going up. We are concerned about that.”