Watch the video interview –

By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Independent curator Suzan Shown Harjo, a Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee from Oklahoma living on Capitol Hill, is seeing a long-held dream come to fruition at the Smithsonian Museum on the National Mall.

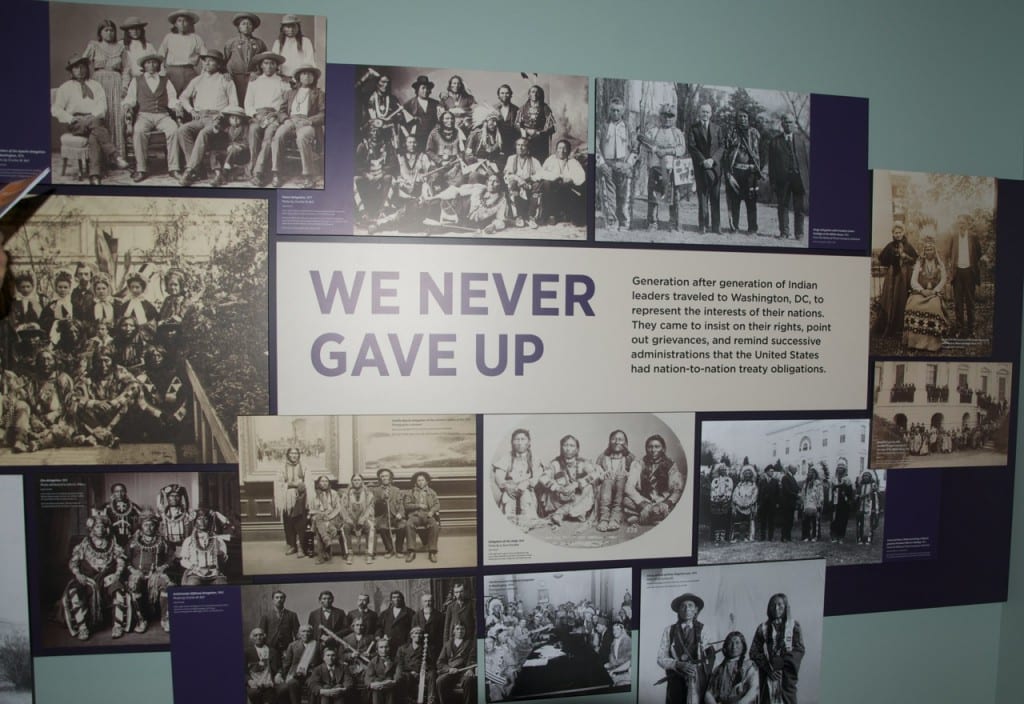

An ambitious project that really started in 1967 — but began in earnest in 2003 — has finally come before the American public showing the relationships over the centuries between the Indigenous nations and the new American nation through a study of hundreds of treaties.

“It’s a story that hasn’t been told,” Harjo said in a video interview at the museum during the opening week. Now we are telling it.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian opened the exhibit to the public on Sunday, Sept. 21 on the 10th anniversary of the opening of the museum. It is being billed as “the museum’s most ambitious effort yet” to present the history of the relationship between the United States and American Indian Nations, through their treaties, “in the largest historical collection ever offered to an audience.”

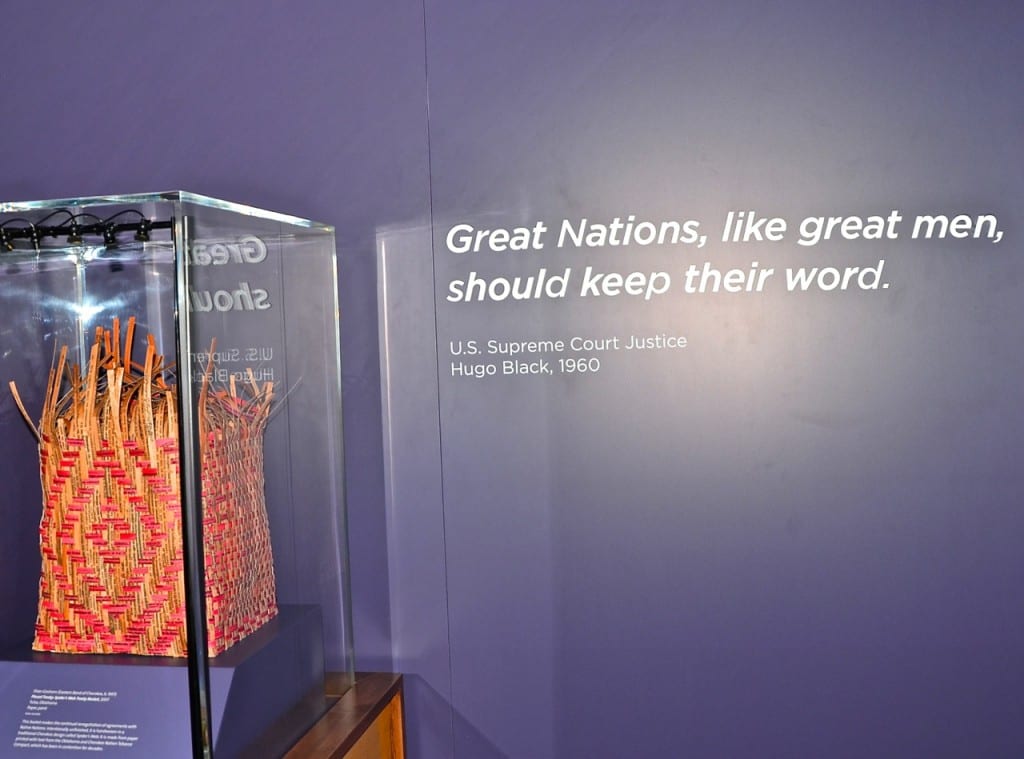

A quotation from a U.S. Supreme Court dissent in a lawsuit between a power company and an Indian tribe were chosen by Harjo to close the exhibit. The famous words of Hugo Black from Alabama in Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation were almost chosen as the title for the exhibit itself: “Great nations, like great men, should keep their word.”

So the 200-year-old question is: Did agents, negotiators, and representatives of the United States keep their word?

“It depends on what the word was,” Harjo says. “They promised to take our land — and they did,” she said, laughing. “In that sense they kept their word.”

But she gives the nation as a whole credit for keeping its word over time in the broad, general sense by building relationships, keeping relationships and “not abrogating” entire treaties.

“Breaking provisions of treaties — very common,” she said, quoting past Seneca tribal president Maurice Johns. “Our treaties haven’t been broken. They’ve been stretched and stretched to the breaking point.”

While the thrust of the exhibit tends to focus on the less told story of Native American removal from north to south as well as from east to west, she talks about not just the decimation but the near obliteration of the American Indian tribes in the South.

“The whole Southeast was ethnically cleansed through States Rights,” she said. “Powerful states working with Andrew Jackson, claiming states rights to get rid of all the Indians in their territories. The people don’t know the whole of that story.”

What she would like for people to take away from the exhibit is that “these are their treaties too .. not just the Indians’ treaties. Most of the visitors have a stake in this still, rights and responsibilities. They benefit from them.”

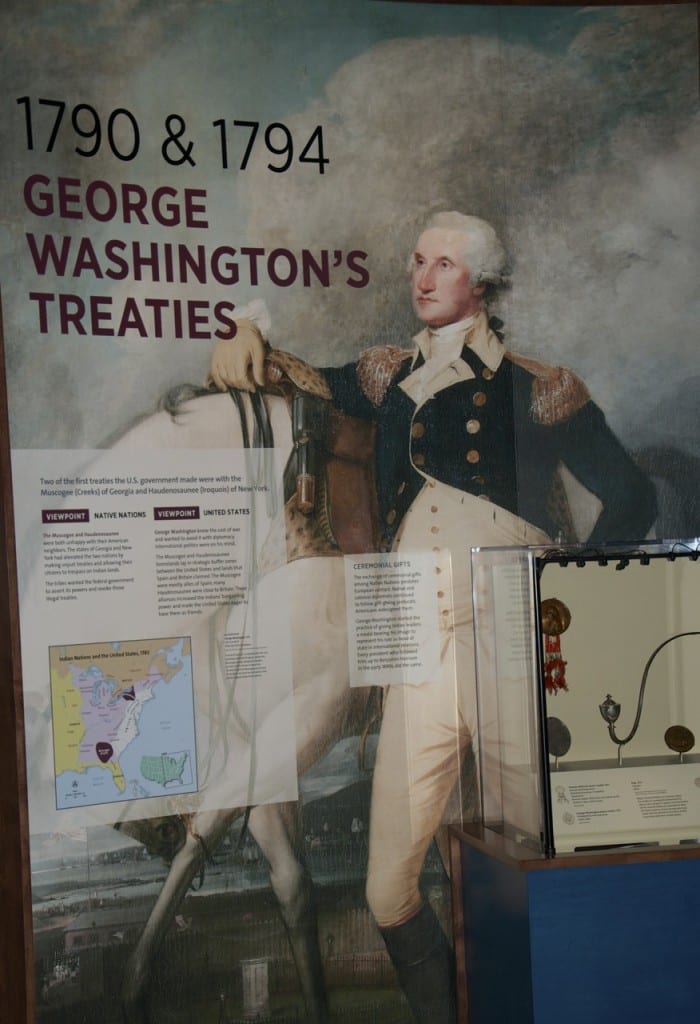

The U.S. gained territory as well as peace and friendship with the treaties, in most cases without having wars, and the federal government gained “preemption” over states, Ms. Harjo says, which was for the most part a good thing for Native Americans. She cited a quote from U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, who once called the states the “deadliest enemies” of the Indians.

“This is the case,” Harjo says. “This has been our experience.”

Why?

“Because they were the nearest, immediate competitor for Indian resources,” she said.

So what did the native nations gain from these treaties, even if some provisions were broken?

“Native nations needed a protector,” she indicated, against the states as well as the flood of people coming in from Europe, bringing with them all manner of diseases for which the natives had no defenses.

“People were being pushed and pushed by population and disease,” she said. “Still today we haven’t built up full immunity. So it’s very common today for people to die from influenza.”

In more than 10 years of research, 600 treaties have been discovered and documented, but there exists evidence of others where copies cannot be found.

“People are still looking for some of these treaties,” she said. “Treaties are evidence and a marker of time .. for the relationship that exists between the United States and Native Nations. The basics for that relationship are peace, friendship, forever.”

That’s how it lasts, she said, and is contemporary because it is an ongoing relationship.

In fact, the Obama administration just agreed to pay the Navajo Nation a record $554 million to settle longstanding claims by America’s largest Indian tribe that its funds and natural resources were mishandled for decades by the U.S. government.

“That’s evidence of the nation to nation relationship and the treaty relationship,” Ms. Harjo said.

One of the treaties highlighted in the exhibit is the Navajo-U.S. Treaty of 1868.

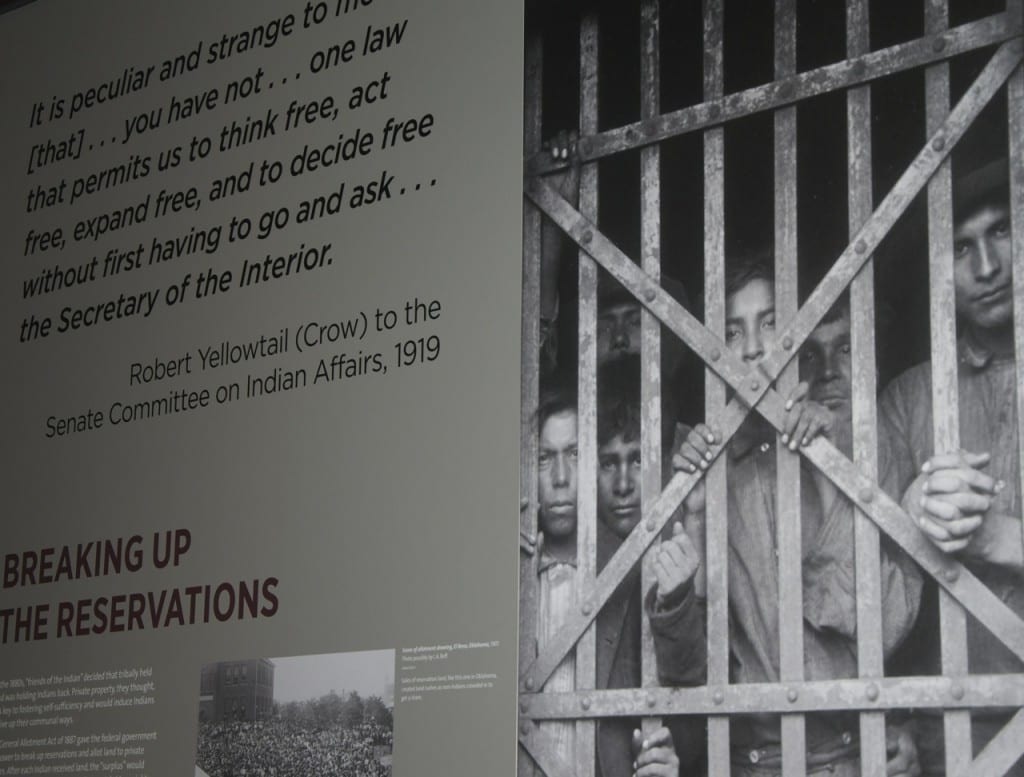

“It was quite a miracle of a treaty because they were scheduled to go to Indian territory,” she said. “They were scheduled for removal after a long confinement in what was essentially a concentration camp.”

They had a long walk but negotiated a treaty that allowed them to go back home.

“They had to walk home,” she said. “That’s what they hoped for (and) worked for. That was the miracle of that treaty, that they were able to achieve that.”

There is plenty of bad news in the exhibit, she said, mainly lawless acts parading as laws put forward by the states, criminalizing native religion, dancing, even long hair.

“We face those in an unflinching way in this exhibit,” she said. “But there are also very hopeful histories like the Navajo, who have gone on to increase their reservation … to one that’s larger than West Virginia.”

People need to understand the importance of the “convenient chain,” she said, one of the historical conventions of the 1700s and 1800s where leaders of the U.S. and native nations would periodically meet to “polish” the relationship, renew their friendship.

President Barack Obama made a campaign promise to have such a meeting with tribal leaders every year.

“He’s kept that promise,” Ms. Harjo said. “He does. Last year he talked about the convenient chain. He understands that. He understands the spirit of treaty making.”

The exhibition focuses on historic episodes of treaty-making and features nine original treaties on loan from the National Archives that will rotate throughout the exhibit’s run. Each treaty represents diplomatic agreements between the United States and Native Nations that remain in force to this day.

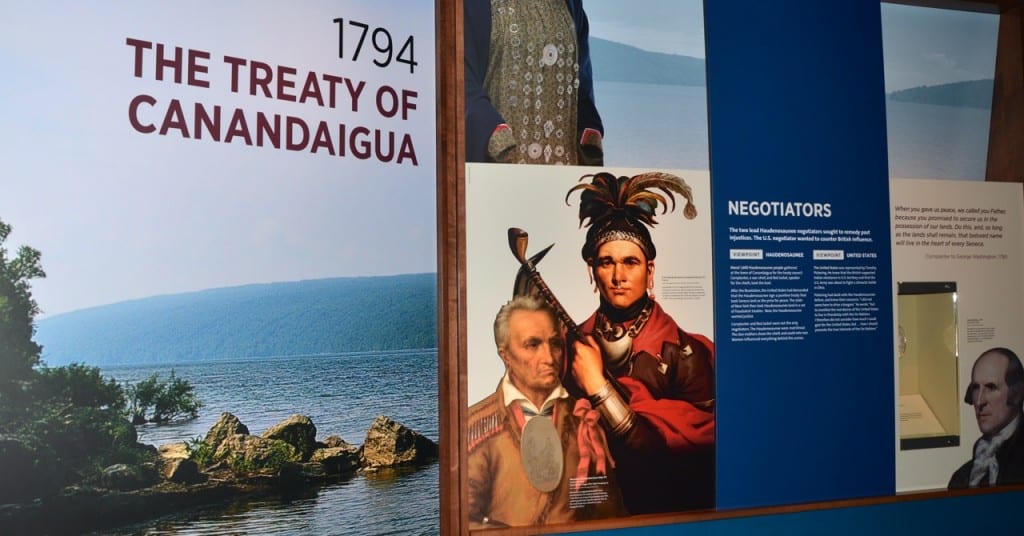

The first to be exhibited is the Treaty of Canandaigua between the Haudenosaunee (the Six Nations, or Iroquois Confederacy) and the “fledgling” United States. One of the earliest treaties made, it was signed by Cornplanter, Red Jacket, Handsome Lake and President George Washington in 1794.

The exhibition, in development for 10 years, offers visitors the hidden stories of the United States and American Indian Nations diplomacy, the history of how the states were ultimately drawn and how promises were kept and broken and renewed with Native Nations, according to the museum.

The story is woven through five sections: Introduction to Treaties; Serious Diplomacy; Bad Acts, Bad Paper; Great Nations Keep Their Word; and The Future of Treaties.

The exhibition also features three original media productions: “Nation to Nation,” a four-minute video that will introduce the main themes of the exhibition; “Indian Problem,” a 10-minute video that shows the cultural side of the shift in power relations between Native Nations and the U.S. government; and “Sovereign Rights,” a four-minute video that covers the topic of termination of tribes. All three videos are narrated by Robert Redford.

“The history of U.S.-Indian treaties is the history of all Americans,” said Kevin Gover (Pawnee), director of the National Museum of the American Indian. “We cannot have a complete understanding of what it means to be Americans without knowing about these relationships, whether we are Native Americans or not.”

Photos

Tourists come to the opening of ‘Nation to Nation’ exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian: Glynn Wilson

A wide angle view of the main entrance atrium at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian: Glynn Wilson

See another slide show of images from the Smithsonian…

More than 125 historical and some contemporary objects from the museum’s collection and private lenders — peace medals given to Native Nations by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson; the pipe of Chief Washakie, who was present at the 1851 Horse Creek Treaty; the sword and scabbard of Andrew Jackson (on loan from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History); and iconic memorabilia from the American Indian Movement — tell the story of living side-by-side from the birth of the United States to the present.

Wampum belts, richly beaded pipe bags, a Seneca dress, Navajo blanket, Cheyenne painted deer skin depicting the Battle of Little Big Horn, Potawatomi medicine bags, tomahawks, baskets, archival photographs and more highlight historical moments.

For more details and to read the actual treaties featured in the exhibition, visit AmericanIndian.si.edu. Join the conversation on Twitter @SmithsonianNMAI and use the hashtag #HonorTheTreaties.

___

This photo was discovered on the web and purchased to be a part of the exhibit to represent the treaty signed by Chief Chinnabee of the Cherokee Nation. It was first published in The Locust Fork News-Journal here: Photo Gallery: Talladega National Forest

Chinnabee Silent Trail Falls near the Lake Chinabee and Cheaha State Park in the Talladega National Forest, Alabama: Kenny Walters

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal.

I enjoyed this. thanks for sharing.reita

Thanks Reita. I hope you one day get to travel to Washington, D.C. to see it. I think you will better understand the exhibit after reading this story and watching the video.